Updated June 10: The Jay Jones campaign says he has visited Lee County when he was growing up.

Doug Wilder set a standard that few candidates since him have met.

In 1985, he formally launched his campaign for lieutenant governor in the most unlikely place possible: the Cumberland Gap, the westernmost point in Virginia.

There was a certain political brilliance in Wilder going as far away from the state capital as he could. Few believed that he could win, that Virginia wasn’t ready for a Black candidate — so Wilder went to the whitest part of the state, Southwest Virginia. That guaranteed lots of free news coverage for a candidate who didn’t have much money, and it helped him make the rhetorical case that he was running to represent all Virginians. It also didn’t hurt that most of Southwest Virginia then was still strongly Democratic territory.

Wilder was greeted with a warm reception, lots of free publicity and, that fall, 59.2% of the vote in Lee County.

Lots of things have changed over the past 40 years, not the least of which is the seismic realignment of Virginia’s westernmost counties from Democratic bastions to Republican ones. Wilder that year won 3,688 votes (and a landslide margin) in Lee County. Four years ago, the Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor picked up 891 votes in Lee — just 12.4% of the total.

Democrats today don’t have much reason to campaign in Southwest Virginia at all — there just simply aren’t many votes there for them. And if they do, they have even less reason to make it to Lee County.

Bristol, sure, that’s easy. It’s on Interstate 81 (and there are TV stations to cover a visit). That certainly seems sufficient to check off the Southwest box.

However, there’s still a lot of Virginia west of Bristol. It’s just hard to get to. From Bristol, it’s about an hour and a half to Jonesville, the county seat of Lee County. Even then, you still have about a 45-minute drive to get to the westernmost tip of Virginia — assuming you don’t get stuck behind a slow-moving truck.

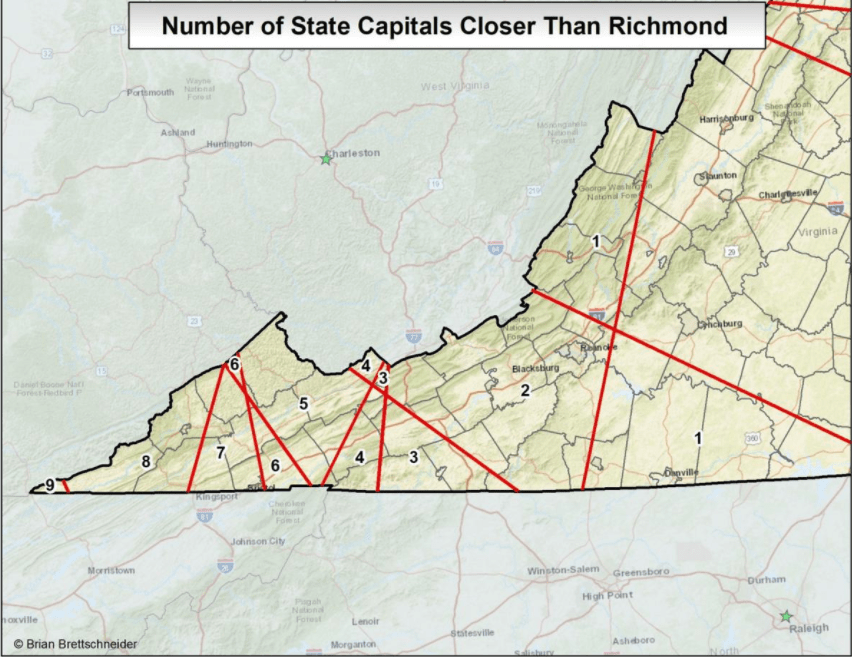

The reward if you get there: a beautiful view and the talking point that you now stand in a part of Virginia that is closer to nine other state capitals than its own.

Next week, Virginia Democrats hold a primary to nominate their candidates for lieutenant governor and attorney general; Abigail Spanberger is already the party’s nominee for governor. Cardinal asked them all a series of policy questions that you can find in our Voter Guide. Cardinal’s political reporter, Elizabeth Beyer, asked them some additional questions, which you can find in her stories here, here and here. All of those were policy-focused questions, too, except for one: How far west have you been in Virginia?

This is probably not the decisive question that will determine the winner. For any Democrats who haven’t made up their mind yet, you may want to check out my column on 10 ways to help you make your decision. Still, I found the candidates’ answers to this question about how far west they’d been to be illustrative.

Only three of the current 12 statewide candidates (that list will shorten after next week’s Democratic primary) have been to Virginia’s westernmost county.

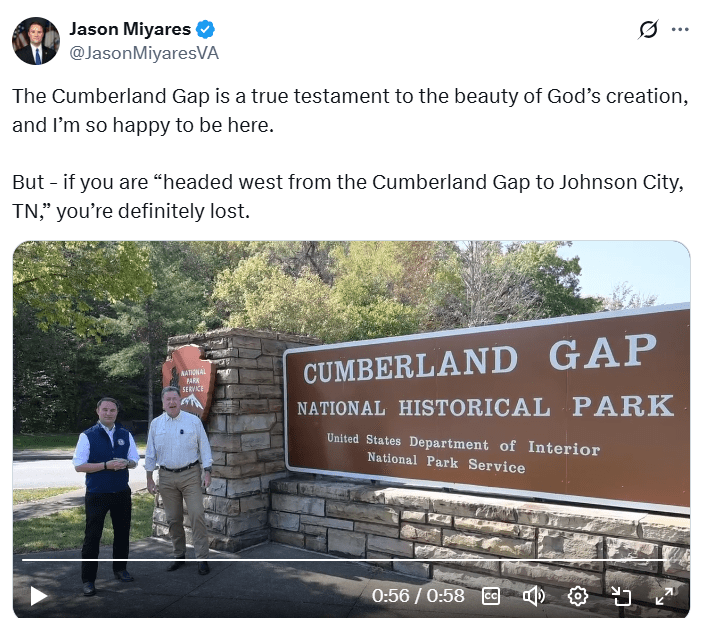

Both Lt. Gov. Winsome Earle-Sears, the Republican candidate for governor, and Attorney General Jason Miyares, who is seeking reelection, have been to Lee County, although they have the advantage of having run statewide once already. Miyares, in fact, was in Lee County on Monday for a law enforcement roundtable at Pennington Gap. Two years ago, he and former Gov. and Sen. George Allen posted this video of themselves at the state’s westernmost point, at the Cumberland Gap, where they noted that the hit song “Wagon Wheel” that references the gap is geographically wrong:

John Reid, the Republican candidate for lieutenant governor, has not been to Lee County, although he has been to Scott County, one county away. Only one of the Democratic candidates has been to Lee County; the campaign of attorney general Jay Jones says he was there with his family when he was growing up.

Some had never been west of the I-81 corridor — Shannon Taylor to Abingdon, Aaron Rouse to Bristol. Some had been farther west, although not all the way west — Alexander Bastani to Russell County, Babur Lateef (who has served on the University of Virginia Board of Visitors) to the University of Virginia’s College at Wise, Levar Stoney to Norton and a coal mine in Coeburn when he was secretary of the commonwealth. Ghazala Hashmi hasn’t been west of Floyd County in this campaign but in the past has been as far west as Scott County. (Of note: She also was one of only two votes in the state Senate against a bill that would have rescinded the charter for the town of Pound in Wise County.) You can see all their answers in the accompanying list.

How far west have candidates been?

Governor:

Winsome Earle-Sears (R): Lee County

Abigail Spanberger (D): Norton

Lieutenant governor:

John Reid (R): Scott County (Devil’s Bathtub waterfall)

Alex Bastani (D): Russell County

Ghazala Hashmi (D): Scott County

Babur Lateef (D): Wise County

Aaron Rouse (D): Bristol

Victor Salgado (D): Did not respond

Levar Stoney (D): Norton

Attorney general:

Jason Miyares (R): Lee County (Cumberland Gap)

Jay Jones (D): Lee County prior to this campaign

Shannon Taylor (D): Abingdon

Now, there’s not much practical reason for a Democratic candidate these days to go to Southwest Virginia and certainly not to Lee County. In last year’s congressional primaries, there were more Democratic votes cast in some precincts in Northern Virginia than there will be in the whole of Lee County in this year’s primaries. However, I will happily get up on my soapbox and make the case that every statewide candidate — Democratic or Republican — should make a point of visiting Lee County.

One reason is simply symbolic. If a candidate wants to claim they’re representing all Virginians, there’s no better way to demonstrate that than to go to literally the farthest corner of Virginia. Of course, when they do, those candidates shouldn’t say they’ve gone to the farthest corner. People in Southwest Virginia will counter that the Cumberland Gap isn’t where Virginia ends, it’s where Virginia begins. That’s not exactly so historically, but you get the idea: “Far Southwest Virginia” isn’t far to the people who live there; it’s the halls of power in Richmond that are.

Speaking as someone who has been there, I can testify that your perspective on Virginia changes when you start counting all those other state capitals that are closer than Richmond — yet the laws passed in Richmond apply just the same. Whoever our next governor, lieutenant governor or attorney general is won’t be spending much time thinking about Lee County; that’s just a matter of numbers. Those future officeholders could learn quite a bit, though, in Lee County, that might (or should?) change how they govern. For instance:

1. Virginia’s economic disparities are vast.

At some level, we all understand this. Every state has its affluent places and its not-so-affluent ones. But let’s talk real-world examples and not broad phrases. Last year, the General Assembly passed a raise for teachers, contingent on local governments providing a match. In some places, that probably wasn’t even an issue. In Lee County, the board of supervisors didn’t come up with such a match. For the lack of $154,027, the county passed up a state match of $745,664. If the county can’t come up with $320,195 for the new fiscal year, it will miss out on a state match of $1,550,102.

You could, of course, argue that the Lee supervisors were simply too parsimonious or, perhaps, insufficiently interested in education. However, let’s look at the world as they see it. There’s simply not much in Lee County to tax. Lee isn’t overrun with data centers the way Northern Virginia feels it is. The median household income in Lee County is $42,269; that’s not the lowest in Virginia, but it’s a lot different than the $178,707 in Loudoun County. I can already hear our readers in Loudoun responding to point out that the cost of living is higher there, too, and they’re right.

However, there are other factors that limit Lee County in a way that local governments elsewhere don’t face. The population is older; nearly a third of the population in Southwest Virginia is over 65, only about 18% of the population in Northern Virginia is. A county where such a large percentage of the population is living on fixed incomes is a county that simply doesn’t have much flexibility. Where, exactly, was this extra money supposed to come from? Raising property taxes on a lot of older, low-income people doesn’t seem like something either political party would find tenable.

What seemed like an easy idea in Richmond — let’s give teachers a raise and require a local match — wasn’t quite so easy once it got to Jonesville.

2. The farther away from Richmond you are, the more important state government is.

This may seem backwards, but here’s how I figure this. Rural governments get most of their school funding from Richmond. Lee County doesn’t get the most per student in school funding; that distinction belongs to Scott County next door, where 66% of school funding comes from the state. In Lee, it’s 50.4%. In Arlington County, the figure is 10.1%. This is why the political turbulence in Washington matters: Reducing the federal workforce may be good for the country (others can debate that), but if those cuts slow down the economy in Northern Virginia, that’s bad for the state treasury and ultimately bad for all rural counties who look to Richmond to keep their schools funded.

3. Southwest Virginia has assets the rest of the state doesn’t even know exist.

Here’s one: We have a national shortage of veterinarians. Do you know which school graduates more veterinary students each year than any other? You probably didn’t guess Lincoln Memorial University. It’s across the line in Tennessee, but those students now get part of their training at a facility in Ewing.

When Gov. Glenn Youngkin held a ceremonial bill signing for a new law to set up a program to produce more large animal vets, he did it at a farm in Montgomery County. That makes sense: close to the vet school at Virginia Tech and in the district of state Sen. Travis Hackworth, R-Tazewell County, who sponsored the measure. But there’s an even bigger vet school that’s partially located in Lee County.

4. People in Lee County can’t take for granted some of the things other Virginians do.

Take health care, for instance. In 2013, the hospital in Lee County closed. It’s since reopened, but that’s something of a miracle because rural hospitals across the country are financially stressed. Because of the large percentage of the population that’s on Medicaid, it’s often Medicaid funding that keeps rural hospitals open. We’ve addressed that in more depth in other columns, but suffice it to be said here that in a place like Lee County, these philosophical debates in Washington have a very practical impact. Nobody in the urban crescent has to worry about their local hospitals — plural! — closing. Throughout much of rural Virginia, that’s a real concern, as people in Lee County and Patrick County can attest.

5. Virginia is a diverse state in ways that aren’t always apparent.

Candidates often talk about what a diverse state Virginia is. They usually mean racial diversity or geographical diversity or economic diversity. There are other types of diversity, though, some of which don’t become fully apparent until you go to Southwest Virginia, and especially Lee County.

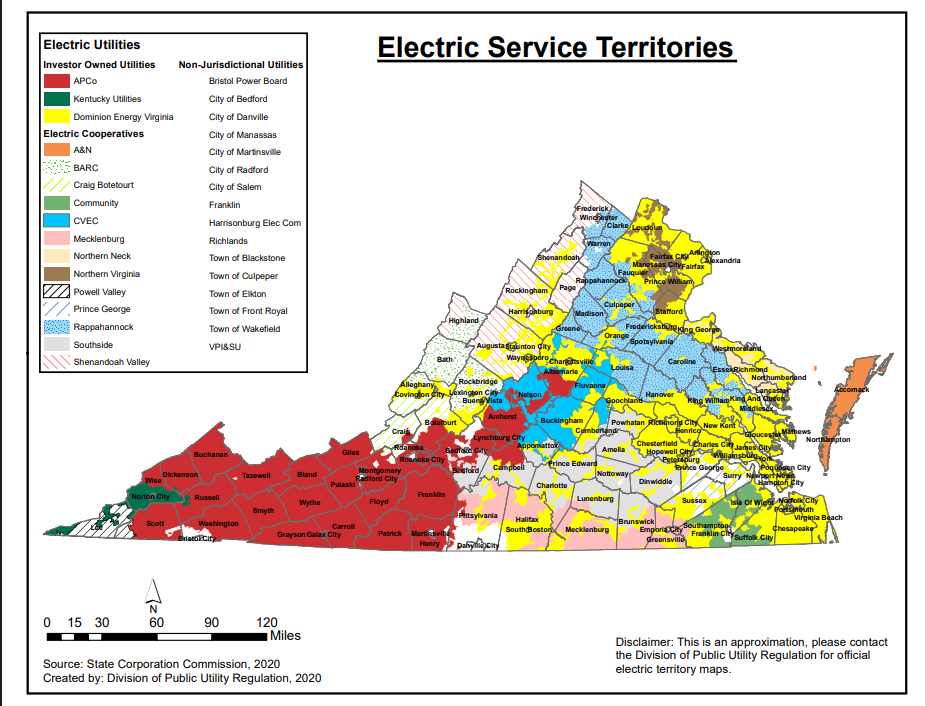

I was recently interviewing some environmental leaders about Virginia’s energy policies. They framed their answers in terms of how their complaints or proposals would apply to Dominion Energy. I gently tried to remind them that Dominion has only a scant presence in Cardinal’s coverage area; Appalachian Power is the main utility out here. (Disclosure: Dominion is one of our donors, but donors have no say in news decisions; see our policy.) Out here, Dominion is somebody else’s utility. However, right now, we have a Republican candidate in one House of Delegates primary (Mitchell Cornett of Grayson County) who is basing much of his campaign on running against Appalachian Power. However, if you go to Lee County or some other parts of Southwest, even Appalachian’s service territory runs out — and the local utility is a subsidiary of Kentucky Utilities.

The Tennessee Valley Authority even extends into Lee County, not for power delivery but for management of the rivers that flow into its hydroelectric operations further south. The TVA works with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources on stream access projects along the Powell River.

The rivers in much of Southwest run south, into Tennessee, and so do people. Migration patterns show that when people move out of Lee and Scott counties, most of them move to a different state — primarily Tennessee, just across the line.

That may seem geographically obvious, but there are cultural differences that come with all this. Most of Virginia falls within the sphere of influence for Washington-based sports teams. Once you pass Lynchburg and Roanoke that ceases to be true — that’s where, in football, you start picking up the Charlotte-based Carolina Panthers radio network. In parts of the westernmost tip of Virginia, though, football fans are in range of Tennessee stations broadcasting the Nashville-based Tennessee Titans. These cultural differences are even more pronounced in baseball. The Cincinnati Reds have long had a strong fan base in Southwest Virginia, thanks to a radio network that includes affiliates in Abingdon and Wise in Virginia and Johnson City, Tennessee. That’s part of the rationale for why the two teams playing a game at the Bristol Motor Speedway on Aug. 2 are the Atlanta Braves and the Cincinnati Reds.

I can’t guarantee that a candidate who visits Lee County, turns on the radio and picks up a Cincinnati Reds game is going to suddenly change some core principle — nor should they. However, they might gain some appreciation for just how diverse the state really is, and ideally that ought to help make them a better representative for all of Virginia. I’ll even offer an incentive: If any statewide candidate visits Lee County and sends a picture from there, I’ll run it in our weekly West of the Capital political newsletter. If you’re not already signed up, you can sign up here:

Today, I dealt with five broad reasons why statewide candidates ought to visit Lee County. Later this week, I’ll spell out 25 specific places in Southwest Virginia that candidates should visit where they might learn things to inform their policy decisions.

Virginia primary is one week away

Virginia holds primary elections on June 17. Democrats have statewide primaries for lieutenant governor and attorney general. There are 17 primaries for House of Delegates nominations (nine Democrats, eight Republicans) and, in the western part of the state, 10 Republican primaries for local offices.

You can see how all these candidates answered our questionnaire (or declined to) on our Voter Guide.