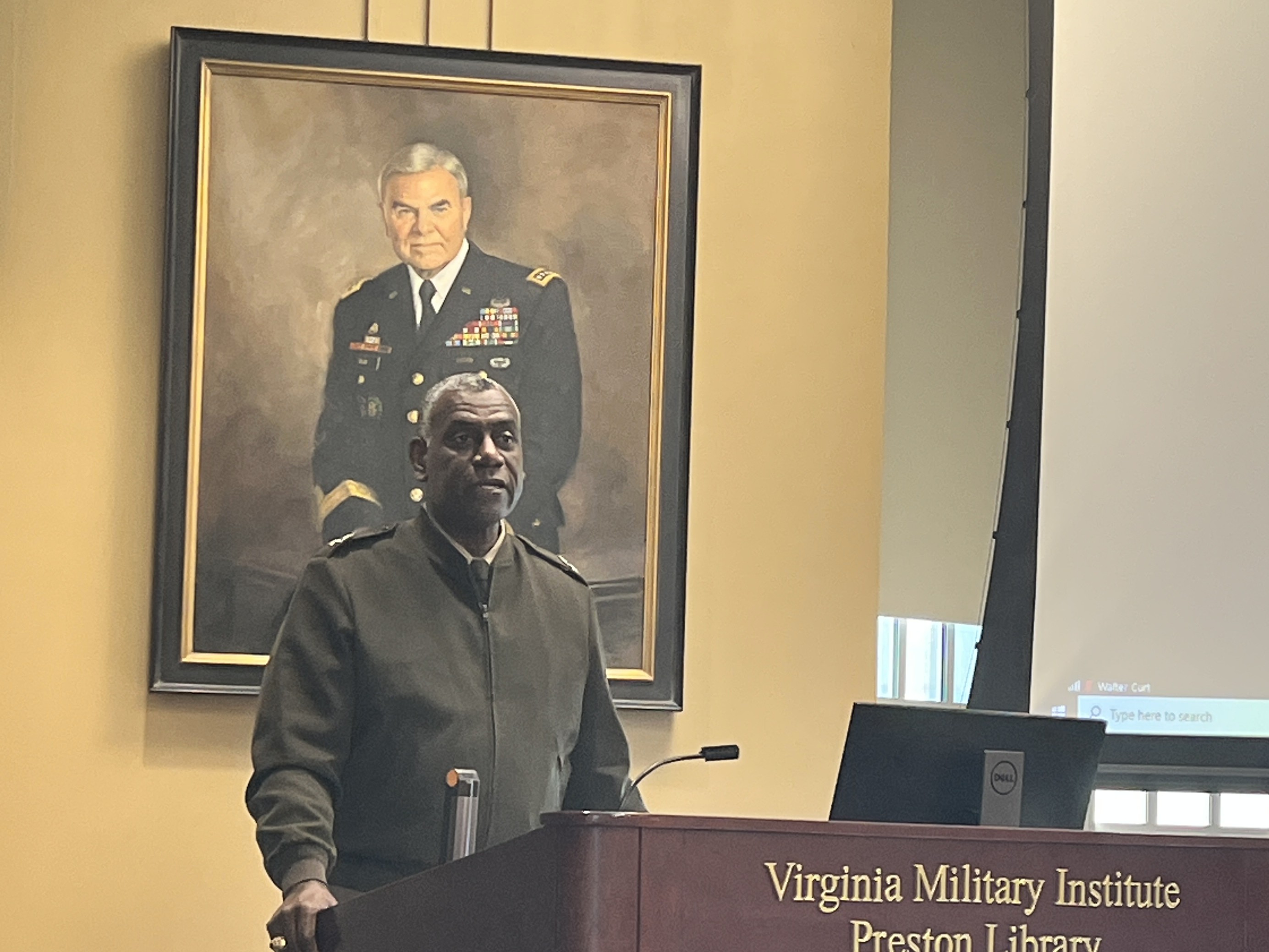

A few days before graduation at Virginia Military Institute, Superintendent (Ret.) Maj. Gen. Cedric Wins spoke with the class of 2025 for the last time. “We’ve come in together and we will leave out together,” he told them.

The class of 2025 was the first to matriculate at VMI under Wins’ leadership. In May, it was the last to graduate before his tenure ends this month.

The state-run senior military college in Lexington has undergone many changes since Wins, its first black superintendent, first took on the role nearly five years ago.

VMI has been grappling with its reputation since fall 2020, when Washington Post reports of widespread racism and sexism there led to a state investigation of the school’s practices and traditions, the resignation of VMI’s longtime superintendent and the relocation of Civil War monuments from campus.

Most recently, the board of visitors, which has recently gone through rapid turnover of its own, has opted not to renew Wins’ contract.

The search for a new superintendent is underway. In the public eye, debate continues about the kind of place VMI, with its deep roots in the Confederate South, should be for incoming generations of students.

At a board of visitors meeting in early May, seven speakers spoke during the public comment period. Six were alumni, their comments showing the wide political spectrum of VMI’s graduates, from scolding the board for ousting Wins despite his achievements reforming VMI to applauding the board for its work to “combat the cancer” of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and restore the institute’s traditions.

The seventh speaker was a student. Isaiah Glover, then in the last few weeks of his second year at VMI, pointed to a “sinister feeling on post,” VMI’s term for its campus. He said that since 2020, the corps has had three commandants — the role that oversees the corps’ military training — and is about to have its second superintendent.

He urged the board to grant the cadet corps a greater influence in the board’s decisions about the future of VMI. Cadets already take an active role in student body governance due to the leadership training built into life at the institute.

Glover, who is Black, cited Wins’ presence at the school as a significant factor in his decision to come to VMI two years prior.

He’d been nervous about moving to Lexington from Pennsylvania, but was comforted by a video he saw featuring Wins. “I was relieved by both his face and his words. It filled my bones with the courage to undertake a 10-hour-plus bus ride here to post,” he said.

“I came to VMI with nothing,” he added. “But an inclusive culture [here] gave me everything.”

Now, as leadership transitions at VMI, it’s unclear what shape the institute’s continuing evolution will take.

Bolstering recruitment efforts amid headwinds

VMI’s enrollment decreased in the aftermath of the state investigation of its culture, which coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prior to 2020, it typically saw incoming classes of slightly more than 500 students, better known as rats. In fall 2022, the admissions cycle that followed the release of the state-ordered equity report, VMI matriculated just 375.

That dip caused concern for institute leadership. The college’s total enrollment has fluctuated over the years, from around 1,300 in the late 1990s to more than 1,700 in the years leading up to 2020. Now, VMI has about 1,500 students.

VMI is the oldest state-supported senior military college in the U.S., one of just a handful of schools that provide military instruction alongside academics. Unlike at the U.S. service academies, senior military college graduates are not required to serve in the military after graduation, though many of them choose to do so.

Students who attend a senior military college over a college that only has a reserve officer training program are looking for an immersive experience, said Col. (Ret.) Craig Alia, vice commandant of the Virginia Tech Corps of Cadets, VMI’s nearest neighbor among military colleges. They know they want to serve in some capacity, though they may not be sure how when they arrive, he said. “They want to serve as leaders and they want to be challenged.”

But with so few schools offering that immersive experience, today’s senior military colleges are all competing for the same students, Alia said. At Tech, he said, recruitment efforts are aided by the size and reputation of the school. About 1,200 cadets live and train together on campus among more than 30,000 civilian students. Many of them are drawn to the military education experience there because of the wide breadth of majors and activities Tech offers, Alia said.

Smaller, more isolated military colleges such as VMI can have a harder time recruiting in the current educational landscape. That’s especially true as colleges face a period of decline in the number of college-age people in the U.S.

VMI has modernized its recruitment efforts over the past few years.

Admissions campaigns increasingly target ninth- and 10th-grade students instead of waiting to court those closer to high school graduation. The school has dropped its $40 application fee. In summer 2023, it started using the Common App, a platform that lets applicants fill out one application for multiple colleges, which has driven a significant increase in applications. It was among the last of the senior military colleges and service academies to offer the Common App, Wins told Cardinal News in May.

The college has also reduced the time gap between notifying a student they’ve been accepted and offering them a financial aid package, Wins said. Condensing that timeline helps keep admitted students interested before another school can tempt them away.

By fall 2024, the number of matriculating students had bounced back from its 2022 low to 498 new rats. Racial diversity among cadets has increased — about 30% of cadets are non-white, compared to about 23% in fall 2019. The percentage of women in the corps has remained steady, according to data published by the college. The institute began admitting women in 1997, the last military college to do so.

This fall semester, VMI anticipates about 500 new students will matriculate.

VMI added diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement and the state investigation that brought some of its controversial features, including alleged hazing practices and claims of widespread racism, to light.

VMI has adjusted its student experience, too. First-year cadets, known as “rats,” once reenacted the Civil War battle at New Market, in which 250-some cadets fought for the Confederacy.

In Lexington, Wins said the atmosphere at VMI has “come a long way from the time I arrived,” and that a cloud hanging over morale at the institute has lifted.

But as Wins implemented new policies and programs at the behest of the state and the institute’s board, both VMI and Wins, as its leader, have faced vigorous opposition from some alumni. Some alumni have complained that changes to make the institute more inclusive have weakened the rigorous atmosphere they felt was integral to their education there and that the removal of the statue of Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson from campus erased the school’s history. The Spirit of Virginia, a political action committee, and The Cadet Foundation both were formed in 2021 during former Gov. Ralph Northam’s administration. The foundation publishes The Cadet newspaper, which reports on campus issues including DEI efforts. According to its IRS filing, the newspaper serves cadets and alumni with cadets maintaining editorial control of its content.

Unlike American service academies, which are run by the federal government, senior military colleges such as VMI have a governance structure that gives the board more power, said Ty Seidule, a visiting professor of history at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York. Seidule, a retired Army brigadier general, is the author of “Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause.”

The board sets the vision for the school, then tasks the superintendent — the sole administrator it hires — with carrying out those goals. Twelve of VMI’s 16 appointed board members must be alumni.

But the power to select those board members ultimately comes down to the governor’s appointments, which can make it challenging to build and maintain a consistent vision for the institute, even during times of less internal leadership turbulence.

The challenges of a one-term governor

Since governors in Virginia serve only one term, Seidule said it’s difficult for VMI to adapt to that frequent change in political direction. “It’s hard for an institution to react that quickly,” he said.

Surmounting its challenges would require “a state consistent in what it wants,” Seidule said. “It doesn’t have that,” he said, due to potential political changes every four years, or sometimes more frequently, depending on party power in the General Assembly.

One example of this: In 2022, new Gov. Glenn Youngkin ordered the state office for diversity, equity and inclusion, created by Northam just three years before, to be renamed for Diversity, Opportunity and Inclusion, and ordered that “divisive” concepts related to history and race be removed from public education. Debate over DEI initiatives at VMI and elsewhere in the state in 2023 led to the sudden departure of the institute’s first chief diversity officer.

Thirteen of the current board members have been appointed by Youngkin, including two quick additions made by the governor ahead of the vote to oust Wins after the General Assembly rejected two appointments Youngkin made in 2024. Bickering by state legislators before and after the board’s nonrenewal of Wins’ contract reopened debate about whether VMI should even exist as a state-run school.

Some previous board members have said that the political party of the governor making appointments didn’t matter in previous iterations of the governing board. Former President Tom Watjen resigned from the board in March with just a year left on his second four-year term, saying it was clear he was out of alignment with the majority that had voted not to renew Wins’ contract.

In an interview with Cardinal News in early April, Watjen acknowledged increasing politicization of the board compared to when he joined it in 2017. “It almost feels like a takeover,” Watjen, who described himself as a moderate Republican, said. For a board, “That’s not a good cultural dynamic.”

After Watjen resigned, President John Adams suddenly left the board as well, less than a year into the role.

Adams was replaced in the interim by Teddy Gottwald, who is often cited by alumni as an example of the board’s increasing politicization. Gottwald is in his second term on the board, but his first term was interrupted in 2020, when he was one of two VMI board members who resigned immediately before the board voted to remove the Stonewall Jackson statue. Gottwald was reappointed to the board by Youngkin in 2022.

The board of visitors has not responded to a letter signed by more than 700 alumni asking for greater transparency from the board. But a few members spoke to defend the board’s dynamic during the April board meeting to elect Gottwald as interim president.

“I have seen no evidence of anybody on the board whom I have served with conducting themselves in any way other than with integrity, respect and honor,” said Kate Todd. “I’m pretty sure at this moment I’m not acting emotionally or with any partisan bias or with any other bias label that could be thrown at me” or other board members, she added.

Her statement repeated the language Wins used in a March statement following the vote to end his tenure, where he claimed he was being pushed out because “bias, emotion and ideology rather than sound judgement swayed the board.”

Wins claimed that the board undermined VMI’s legacy for political gain and said that instead of advancing the school and its mission, “we risk returning to an obsessive focus on our distant past believing it will produce tomorrow’s leaders of character.” He added that the board’s “choice to subject cadets to a cycle of politicization is misfeasance,” endangering both VMI and the nation.

The battle for power on the board of visitors has continued. On Monday, a state Senate committee rejected a list of Youngkin appointments to university boards, with some Democrats expressing reservations about the qualifications and motivations of the nominees. On the list were three appointments to VMI’s board of visitors: the two named days before Wins’ contract was rejected for renewal, and one named in April to fill Adams’ open seat.

Alumni have strong ties — and strong feelings

To weather the political pendulum, Wins said in his May conversation with Cardinal News that VMI and its leadership would do best to lead in “an apolitical fashion.”

“If we remain apolitical, then we can take [political swings] into account and talk about the mission of the institute,” he said. And VMI’s mission of training students for leadership roles “is about as apolitical as you can get.”

But VMI’s continuing effort to remake its image gets slowed down by politics and by its own alumni corps.

The superintendent search committee conducted a survey this spring to learn what the VMI community thought were essential qualities of the next superintendent. Recurring themes, according to a report during a search committee meeting in late April, included a need for unification of the VMI community, leadership ability to navigate political headwinds and the importance of retaining tradition in a changing higher education landscape. The majority of stakeholders who responded to the survey were not students, faculty or staff, but rather self-identified primarily as alumni of the institute.

Alia of Virginia Tech said the experience of attending a senior military college is special. Cadets form quick bonds in their structured training cohorts and “automatically have a cohort of folks they are tied to for life,” he said.

But the special bond that unites VMI alumni could be the thing that continues to splinter the school’s progress.

At senior military colleges, the experience graduates go through is so difficult that “they don’t want anything to change,” Seidule said. “They think anyone who went through it after them won’t get the same thing they got.” That alumni base can be even more resistant to change than a typical alumni group might be.

Lester Johnson, a 1995 alumnus who was appointed to the board by Northam in June 2020, said he’s “kind of stepped away” from VMI since he left the board. His appointment was not renewed in 2024.

He said a lot of African American alumni have done the same. It would be hard for him to attend sports or other events there, “knowing that my school is being led by people who I feel like put the school in a bad situation,” Johnson said, speaking of the board of visitors. “It makes me sad.”

“VMI has a fundamental issue with regard to its alumni base,” that didn’t exist several years ago, he said. “VMI teaches us that we’re all brothers. I question that now.”

Sean Lanier, a 1994 alumnus appointed by Northam in November 2020 to finish Gottwald’s term, said VMI’s leadership needs to move on from a “good old boys” mindset. “You can’t operate today with [the idea], ‘I’m with VMI, screw everybody else.’ Not in Virginia, let alone everywhere else.” Lanier was on the alumni association board before his time on the board of visitors.

He said the success of the institute rides on it being able to increase enrollment and provide more scholarships to incoming cadets. As older alumni classes dwindle in number, the institute needs young people graduating without college debt who will want to contribute as alumni.

Younger alumni don’t have the deep pockets of the generations before them, he said. And even worse, a lot of them are “checked out” because of the political forces tearing at VMI. “It’s going to be hard to recover them.”

________________________

Clarification 4:50 p.m. June 11: This story has been updated to more clearly explain the relationship between the Cadet Foundation and The Cadet newspaper.