In Tuesday’s column, I listed how few of the statewide candidates have been to Virginia’s westernmost county — Lee County, a tiny piece of which is closer to nine other state capitals than it is to its own in Richmond.

Only three of the 12 statewide candidates have been there, and only two of those in the course of a political campaign (Republican gubernatorial candidate Winsome Earle-Sears and Republican Attorney General Jason Miyares; Democratic attorney general hopeful Jay Jones was there earlier in his life). Some of the candidates hadn’t been west of the Interstate 81 corridor. One of those who hasn’t been to Lee County is John Reid, the Republican candidate for lieutenant governor. In the course of our email exchange, he said he planned to return to Southwest Virginia and asked me for advice on things he ought to see.

That question prompted this column, for all the candidates to see. There’s a political reason for a candidate to visit Lee County, even a Democrat who won’t find many votes there: The candidate can then claim he or she is prepared to represent all of Virginia. However, there are many places in Southwest Virginia that a candidate should visit to learn things that will come up in policy decisions later on. Since this is 2025, here are 25 of them.

I tried to keep this list focused on places west of I-81, although there are a few sites in Bristol and Washington County that made the list, simply because they represent important policy issues that prospective statewide officeholders ought to know about. The goal was to find places that represent some policy choice unique to Southwest Virginia, although that line isn’t always so bright and clear because many issues are statewide ones — they just look different in the westernmost corner of the state. Enough chatter, though, let’s get to the list.

1. Lee County Community Hospital

Whatever a candidate’s views on health care policy are, they need to accommodate these facts: Rural hospitals are under financial stress and rely heavily on Medicaid payments. Lee County lost its hospital in 2013. With much difficulty, the facility in Pennington Gap reopened as the Lee County Community Hospital in 2023. Lee is one of the lucky places. Patrick County saw its hospital close, too, and a new owner is hoping to get that reopened. There are lots of health care issues that are more visible in Southwest Virginia — the opioid epidemic began here. The region has trouble attracting doctors and other health personnel. Cardinal’s Emily Schabacker has written about how hard it is to find maternal health care in rural areas. I could devote an entire column just to the health care issues involved here. For abbreviation purposes, let’s just combine them all under one heading — and a visit to this hospital could be a good learning experience for any candidate.

2. Buchanan Mine #1

This is a more important trip for both parties, although for different reasons. A combination chemistry and geology lesson first: Not all coal is the same. Thermal coal, or steam coal, is what’s burned to make electricity — that’s the controversial coal. And then there’s metallurgical, or “met” coal, which is burned to make steel. There’s no practical way to make steel without met coal. The irony of the infrastructure bill that Democrats passed (with some Republican help) in 2021 was that it was indirectly a pro-met coal bill. If you want to build more bridges, you need more met coal mined.

Democrats would benefit from understanding that coal will remain important to the Southwest economy even if we’re not burning any for electricity. Republicans would benefit in another way: Virginia exports a greater share of its coal than any other state, so if a trade war of tariffs and retaliatory tariffs reduces international trade, then that’s bad for those employed in the met coal business. The Coronado mine has already laid off 140 workers in Buchanan County. The company’s not saying why, but it comes against a backdrop of China reducing its coal purchases from the United States and buying Canadian coal instead. So, yes, a mostly Democratic bill may have helped the met coal industry while a Republican president’s trade policy may have hurt it.

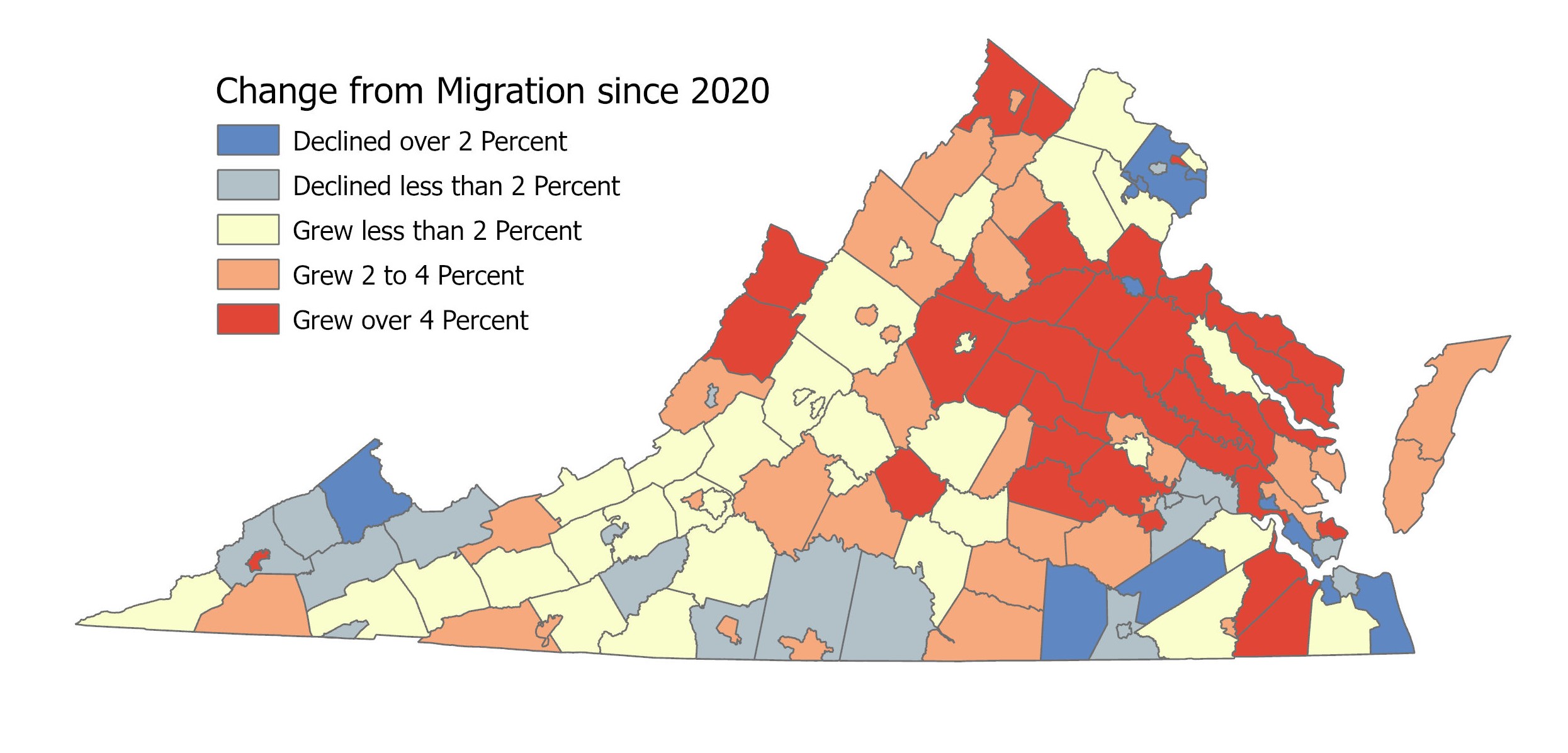

3. Buchanan County, an epicenter for outmigration

While a candidate is in Buchanan County to learn about met coal, there’s another lesson that can be learned. Until this past year, Buchanan County was losing population at a faster rate than any other county in the state. This past year, Sussex County dropped further and faster. Nonetheless, Buchanan County still ranked second.

Most of Virginia is now seeing more people move in than move out. That trend has accelerated since the pandemic. Still, there are some places that aren’t benefiting from that trend — and many of those are in Southwest Virginia. These are counties that are losing population in two ways: They’re older, so deaths exceed births, but they’re also seeing more people move out than move in. Some counties in Virginia worry that they’re seeing too much growth; there are some counties in Southwest with the opposite problem. If a statewide officeholder absorbed only one lesson from a visit to Southwest, this might be it, because so much else flows from that.

Here’s a challenge for our next governor: What can she do to reverse net out-migration in every county in the state?

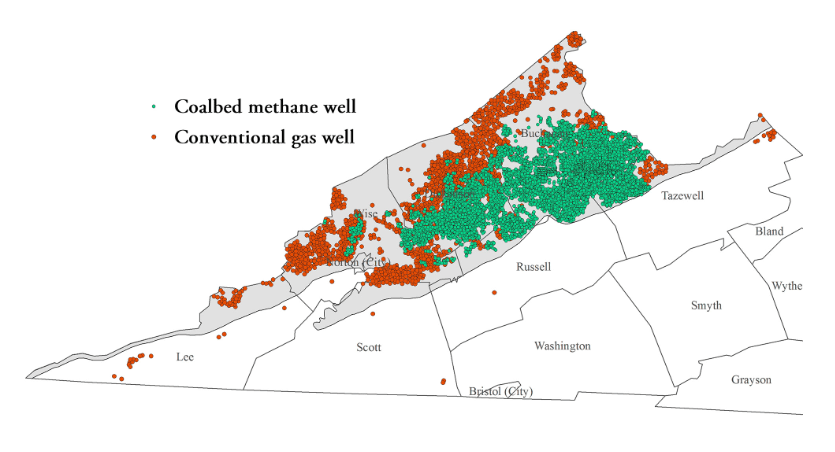

4. Natural gas wells in Southwest Virginia

Virginia is the nation’s 18th-biggest producer of natural gas. That may not be Democrats’ preferred way to generate power, but that doesn’t change the fact that these wells are still here — in six counties in Southwest Virginia, but most especially in Buchanan, Dickenson and Tazewell. These 8,398 permitted wells produced an estimated $217.1 million worth of gas in 2023, the most recent figures available. Republicans don’t need much convincing about natural gas; Democrats might need more, but even they ought to understand the economic role in the region. If some energy policy designed to curb carbon emissions were to shut down natural gas production, there would be environmental consequences — but also economic ones.

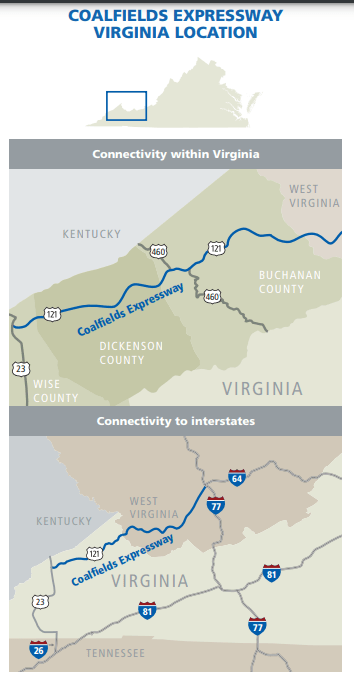

5. The Coalfields Expressway

Or rather, what someday may be the Coalfields Expressway. The road is supposed to run from the Wise County town of Pound, near the Kentucky line, to Beckley, West Virginia, and a connection with the West Virginia Turnpike (interstates 64 and 77). Much of the 65-mile West Virginia section is complete; the proposed 50-mile portion in Virginia is mostly a dream, although work on some sections is underway around Grundy.

Why is Virginia being bested by West Virginia? For one thing, the coal country of West Virginia means a lot more in Charleston than the coal country of Virginia does in Richmond.

The proposed road is also hugely expensive. A Virginia Department of Transportation report last year put the cost at $2.5 billion. While that wouldn’t have to be paid all at once, that’s still about two-thirds of the state’s annual road construction budget, which this year is $3.78 billion.

The purpose of the road is to open up Buchanan and Dickenson counties for economic development. Goodness knows they need that, but if you’re a commuter stuck in traffic on Interstate 66 in Northern Virginia at rush hour, you’d probably like to see the state’s transportation money spent on unclogging things there and not blasting away some mountains in far-off Southwest Virginia to build a road in hopes that a better highway would help lure employers. We have traffic jams now that need to be relieved; making the case for funding for a road through two counties losing population is harder to justify. Still, a future state officeholder ought to see the problem in Southwest Virginia firsthand. You really haven’t experienced Southwest Virginia until you’ve tried driving from Haysi to Vansant. Even the better roads in Southwest Virginia can be adventurous. A few years ago, state police were escorting Gov. Glenn Youngkin from the airport in Abingdon to a speaking appearance in Wise County when the motorcade was delayed because a giant boulder had come tumbling down a mountainside and was blocking the road.

6. The University of Virginia’s College at Wise

This is the westernmost state-supported four-year school in Virginia. Indeed, the only state four-year school west of Radford. Between its name and its location, UVA-Wise often doesn’t get the attention it deserves. The school is small, but not the smallest in the state. That distinction belongs to Virginia Military Institute, whose history and politics make it a frequent newsmaker. VMI’s enrollment is 1,527; UVA-Wise had 2,280 students this past year, putting it behind the University of Mary Washington, which had 3,826. While UVA-Wise naturally draws heavily from the region, that’s not the entire student body. I spoke to a class there earlier this year and had the students raise their hand by area code. Every area code in the state was represented.

Colleges all across the country are grappling with enrollment declines, some of them a consequence of the so-called “enrollment cliff” — a drop in potential college-age students due to declining birth rates. However, enrollment at UVA-Wise is rising. The enrollment last year was the school’s highest in 12 years. Former Gov. Ralph Northam once proposed making UVA-Wise a center for renewable energy research as a way to spur economic growth in the region; that idea didn’t take hold, but in the modern economy, any university is an economic asset. What can the next governor do to make UVA-Wise even more of an asset to the region?

7. Schools in Scott County and Lee County

Every candidate says they want better schools. Great. Now let’s talk about the troublesome details, especially about funding. Scott County gets 66% of its school funding from the state; no other locality is so dependent on Richmond. Still, rural localities traditionally have gotten most of their funding from the state. By contrast, Arlington County gets only 10.1%. The state’s funding formula is a complicated thing, but it’s basically driven by poverty and affluence.

There are plenty of inequities in the formula, and occasional talk that it needs to be redone. However, that’s a tricky thing because of counties such as Scott that are so reliant on state funding and naturally wary that any change might leave them at a disadvantage. That means any change to the funding formula has to be a win for everybody, and that’s hard to do.

Meanwhile, Lee County provides a different type of example related to school funding. The General Assembly has passed money for teacher raises, but they’ve been contingent on a local match. Lee County hasn’t provided the match because it didn’t think it could afford what would be an inconsequential sum in some places but is very consequential there. For the lack of $154,027, the county passed up a state match of $745,664. If the county can’t come up with $320,195 for the new fiscal year, it will miss out on a state match of $1,550,102. A governor can brag about signing a budget with money for teacher raises, but that doesn’t mean much in Lee County.

There’s another reason for statewide candidates to visit schools in Lee County …

8. Solar-powered schools in Lee and Wise counties

The coal counties of Appalachia probably aren’t a place where you’d expect to find solar panels on top of schools, but there they are in Lee and Wise. This is all part of an apprenticeship program that has been training students through Mountain Empire Community College, which now offers solar training as a standalone career studies certificate or as part of its larger energy technology associate degree program.

Large fields full of solar panels are often controversial, but rooftop solar usually isn’t. Here’s a way for taxpayers to save money on school heating and cooling bills while also training a new workforce for a new economy. You can read more about this program in this report by Cardinal’s Matt Busse and Lisa Rowan.

9. Ridgeview High School in Dickenson County

This school, in one of the poorest counties in the state, has now won back-to-back Scholastic Bowl championships in its size category. Some years ago, the late St. Paul lawyer Frank Kilgore (no relation to the more famous political Kilgores) was in Richmond to pitch the region as a site for technology jobs. One of the officials in the meeting made the mistake of asking him if Southwest Virginia “has the DNA to fill cybersecurity jobs.” He responded by writing a series of opinion pieces for newspapers around the state to call attention to the region’s high test scores — and then spent more than $10,000 of his own money to buy newspaper ads to trumpet that message. When Ridgeview won its first Scholastic Bowl, who tipped Cardinal News to that triumph? Kilgore, of course. He died last year, but would have surely let us know about the school’s second victory, too.

A visit to Ridgeview would give candidates a firsthand view of the academic skills of Southwest students. It also would underscore some other, unrelated, messages: Ridgeview was founded a decade ago when Dickenson had to close Clintwood, Haysi and Ervinton high schools due to declining enrollment. Dickenson has typically been behind only Buchanan County in its rate of population loss. When Ridgeview was built, it also took one of the last developable sites in Dickenson, which underscores the paucity of flat land in Southwest.

10. Mountain Empire, Southwest Virginia and Virginia Highlands community colleges

Virginia’s community colleges are underfunded relative to four-year schools, even though you can argue that community colleges have more long-term impact on the state. Census stats show that only 54.9% of Virginia’s four-year graduates are still in the state within five years of graduation, while 79.2% of community college graduates are. With four-year schools, we’re educating a lot of workers for other states, and we don’t even get so much as a “thank you.” With community colleges, we’re far more likely to be training our own workers. Statewide candidates can learn something by visiting any of the state’s 23 community colleges, but here’s a special reason to visit these three. In fact, we’ve already mentioned it above.

These schools now have programs in renewable energy. So do other community colleges around the state, but these programs, in or near the heart of what we once called coal country, are particularly noteworthy here. Politicians can argue over how much of our energy supply should come from renewables, but whatever their preferred percentage is, the reality is that some of it’s going to be from renewables — because some of it already is. Even in what might be considered the most unlikely part of the state, these schools are working on training that alternative energy workforce.

Speaking of energy …

11. The Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in Wise County

If you’re driving west on U.S. 58 on the way to Wise, this massive facility appears like something out of a science fiction movie. While Dominion Energy is not the utility for this part of Virginia, Dominion does have this energy plant in Southwest Virginia. (Disclosure: Dominion is one of our donors, but donors have no say in new decisions; see our policy.) Virginia City burns a mix of biomass, coal and coal waste (more on coal waste below). Environmentalists hate Virginia City. They didn’t want to see it built in the first place and would love to see it shut down. They see it as dirty and expensive. Republican legislators from Southwest Virginia are very protective of Virginia City — the facility is a major employer in a part of the state where jobs are hard to find and point out that it’s helping clean up coal waste. Southwest legislators won an exception for Virginia City in the Clean Economy Act that allows it to stay open long past the retirement date for conventional coal plants.

Energy issues are complicated and often ideological. No matter what your position, you can find a reason to cite Virginia City. However, for those who would like to see it shuttered, there’s a practical question: How would you replace those jobs?

12. The wind farm that doesn’t exist in Tazewell County

It’s usually hard to see something that doesn’t exist, but in this instance, it’s not hard at all. Just look at East River Mountain in Tazewell County. In 2009, Dominion bought about 2,600 acres there for a proposed wind farm. It was controversial, so controversial that in 2015, the Tazewell County Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance that included wind farms as “undesirable developments” that were banned from the county. This is a prime example of how hard it is to build energy generation facilities, and a case that foreshadowed the current pushback to solar elsewhere in rural Virginia.

We’ve seen Southside Virginia become a magnet for solar projects, and not everyone is happy about that. There are some in the General Assembly who have warned that the state may need to take over the role of siting large energy projects because too many rural governments are rejecting them. The focus has been on solar, because that’s where virtually all the new power is coming from, but the same principle applies to wind power. In fact, the lack of wind turbines on East River Mountain is a reminder of just how hard it is to build wind power in Virginia. Tazewell blocked wind. By contrast, Botetourt County has enthusiastically welcomed a proposed wind project, but it still took 10 years for the Rocky Forge project from the Charlottesville-based Apex Clean Energy to get approved and start construction. It’s not set to begin producing power until late 2026, which would stretch the project to 11 years.

The fact that it takes so long to get some of these projects online is part of what’s driving the solar boom; solar is relatively easy to get up and running.

13. The data center at Mineral Gap in Wise County

Some in Northern Virginia feel they’re being overrun with data centers. This past session of the General Assembly saw lots of bills introduced to slow down their growth; those bills also generally failed. There’s one part of Virginia, though, where local leaders would love to have data centers: Southwest Virginia. The big talking point is the DP Facilities data center at Mineral Gap in Wise County. (Great name, right?) There are two reasons why it’s hard for Southwest to attract data centers: Data center companies worry about not being able to find a workforce and fret that the internet speeds are too slow. Some data centers can’t be in Southwest Virginia because they need more immediate interconnection with nationwide networks. Some, though, can accept slower speeds. The 22-acre Mineral Gap Data Center stands as an example of a potential technological future for Southwest Virginia. The Energy DELTA Lab is currently working to develop a 450-acre “Data Center Ridge” in Wise County that would use underground mine water for cooling. What can state officeholders do to direct some of those data centers to places that are eager to accept them but aren’t on the radar of data center companies?

One other thing to see: The Mineral Gap Data Center is powered by the first solar development project on former mine land in Virginia.

14. Weed stores in Weber City

Virginia is the only state that has legalized personal possession of cannabis but bans retail sales of weed. This is like saying you can have tomatoes, but only if you grow your own. Not everyone is able or inclined to do that. If you couldn’t find tomatoes at a grocery store, some black market gardener would be doing a booming business with some illicit Better Boys. Throughout Southwest Virginia, we’ve seen stores pop up where you can openly obtain cannabis, law or no law. These are typically set up as “adult share” stores where, if you buy an overpriced sticker or T-shirt, the store clerk will graciously “share” some of the devil’s lettuce. Attorney General Jason Miyares has issued an opinion that says this is still against the law, but the stores remain active. Nowhere are they more visible than in Weber City, a town of about 1,200 in Scott County that appears to have no fewer than four such operations. Why Weber City? It’s just across the state line from Tennessee, where cannabis is still banned.

If you’re a Democrat — and Democrats are in favor of legal retail — then Weber City is a good place to talk about why we need a regulated market, to put these black marketeers out of business. However, Republicans ought to talk about why these cannabis stores are allowed to persist so openly and whether they intend to do anything about them.

15. The flood-stricken communities of Buchanan and Tazewell counties

Hurley, a community in the corner of Buchanan County, wedged in between Kentucky and West Virginia, was nearly washed away by a flood in 2021. The Federal Emergency Management Administration offered little help because it felt the damage didn’t total enough money to merit individual assistance. Never mind that some people lost everything. In effect, the federal government was saying Hurley was too poor to help. The state stepped in with relief funding of $11 million, the first known time that Virginia has gotten into the floor relief business.

In the years that followed, there have been multiple other floods, not just in Hurley but elsewhere in Buchanan County and Tazewell County — plus the more widespread flooding from Hurricane Helene last year. Gov. Glenn Youngkin has earned high marks in Southwest Virginia for his crisis management skills in dealing with these floods. Nonetheless, recovering from these floods is a multi-year process. In July 2022, floods washed away a bridge in Buchanan County. It took two years to get a replacement up — and before it was finished, that got washed away last year. The state has put up more flood recovery money for Southwest Virginia, getting even more deeply involved in the relief business. Any future state officeholder should see how all that’s working (or not working) on the ground.

16. Natural Tunnel State Park, Clinch River State Park, Breaks Interstate Park

Visiting any of these three would be a welcome diversion from some of the other more policy-oriented visits, but state parks are state-funded, so there’s policy here to talk about as well.

17. Spearhead Trails

While we’re talking outdoors, candidates ought to understand one unusual way that Southwest Virginia is trying to develop an outdoors economy. The Spearhead Trails (run by a state authority) are a series of trails, often on old mine property, where you can ride your four-wheel vehicle. Vrrrrrrooooom …

Now for the serious part: These trails have spurred business along their route, but they’ve also drawn criticism from environmental groups who say all this four-wheeling has done “significant damage” to some waterways.

18. The Starlink families of Dickenson, Russell, Tazewell and Wise counties

Broadband access is better than it was, but we still don’t have everyone online. Broadbandnow says only 49.7% of those in Bland County have access. That’s not the lowest in Virginia (that’s 35.2% in Greensville County), but it’s not exactly the 100% in Falls Church, either. While there seems to be universal political support for universal broadband, behind the scenes, there’s been a fight between those who insist on putting fiber in the ground and those who think that satellite internet (through Elon Musk’s SpaceX or Amazon’s Kuiper or some other service) is a better technological workaround. That’s now come out into the open; the Trump administration recently issued orders to do away with a preference for fiber and let satellite-based systems compete on an equal footing for certain contracts. (See this story by Cardinal technology reporter Tad Dickens.)

Before any candidate makes up his or her mind, it might be wise to talk to some families in Wise County. That county became the first in the state to give some students access to satellite internet. See our previous reporting.

19. Red Onion State Prison or Wallens Ridge State Prison

Criminal justice is always a policy issue, and the end result for some cases is that inmates wind up in one of these two prisons in Wise County near the Kentucky line. Red Onion has been beset by allegations that prisoners have been mistreated, so there’s lots to talk about here, no matter what a candidate’s views are. I toured Red Onion a few years ago when Miyares visited the facility; it was probably the scariest thing I’ve done as a journalist, even more so than the time I almost ran afoul of the Pagans motorcycle club over a story I was writing. Even if there were no controversy attached to Red Onion, a future statewide officeholder ought to see the prisons they will be responsible for.

20. The substance abuse treatment centers in Dickenson County

The Happy Valley Industrial Park in Clintwood has an unusual tenant: Dickenson County Behavioral Health Services. Unfortunately, the agency is a fast-growing employer due to opioid addiction. Employment has more than doubled in the past few years, from 35 to 75. Drug treatment centers in Dickenson have doubled as both health clinics and economic development, both for the employment they provide and for the people they hope to help and get back into the workforce. That’s why the Virginia Coalfields Economic Development Authority has helped fund two drug treatment centers in Dickenson — one for men, one for women.

This is a difficult topic; nobody likes to call attention to a community’s problems, but if state officeholders want to understand the challenges confronting the region, this is a necessary stop.

21. Coal waste sites

Nobody knows how many coal waste sites there are across the coal-producing counties of Southwest Virginia. The Virginia Department of Energy (which prefers the shortened title of Virginia Energy, even though that sounds like a power company) has identified 245 such piles — more than 80 in Buchanan County alone — but a 2022 report by the Appalachian School of Law in Grundy noted that inventory is “acknowledged to be incomplete,” although it probably does cover the biggest sites. As for just how much waste coal is in these 245 sites (“pile” suggests something smaller and more compact than what some of these are), nobody knows that, either, because they’ve never been fully surveyed. Some sites that have been cleaned up in the past were pretty darned massive, though. More than 1 million tons were hauled away from the Hurricane Creek site in Russell County when it was cleaned up in 2014.

The Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center mentioned above helps get rid of some of this coal waste, but not all. That 2022 report says only piles within 45 miles of the plant are economically feasible due to transportation costs. That covers 186 sites but leaves at least 59 others out of range. Furthermore, the report says that small sites within the 45-mile range may not be economically feasible for Virginia City, either, “due to the fixed costs associated with removal and remediation efforts.”

These coal waste sites are polluters. They leach into the groundwater or sometimes into streams. That Hurricane Creek site released about 200 tons of waste coal into the Clinch River each year before it was cleaned up, the report says. So much waste coal flowed into Stone Creek in Lee County that the Department of Environmental Quality found it to be “lacking the ability to sustain aquatic life.” Some catch fire, and once they start smoldering, those gob fires are hard to put out. That Appalachian School of Law report outlined ways to speed up the cleanup of these sites. That sounds like required reading for a future governor to me, in conjunction with a visit to one of these sites.

Now we turn to four other places in Southwest Virginia that aren’t west of the I-81 corridor:

22. The proposed inland port site in Washington County

An inland port has nothing to do with water, at least not directly. It’s a freight cargo center that serves two purposes. One, it’s a place to assemble cargo before shipping it to the port. Two, inbound cargo to the port can get sent here to be processed, thus speeding up turnaround time at the port and avoiding bottlenecks. More to the point, these inland ports are a way to direct traffic to that state’s port and not some rival one. Virginia already has one inland port, near Front Royal. The purpose there was to lure Midwestern traffic bound for ports at Philadelphia or Baltimore to divert to Front Royal — and ultimately Hampton Roads — instead.

The inland port itself doesn’t employ many people, but the one at Front Royal has spurred the creation of thousands of jobs in the northern Shenandoah Valley — warehouses and trucking companies. The state has appropriated $2.5 million to begin planning a second inland port, this one in Washington County. It’ll need more money for actual construction. Those seeking to lead the state should understand what this project is about.

23. Bristol’s landfill

Bristol built a landfill that, well, stinks. There are lots of reasons why it’s stunk so much — let’s just say it was poorly built. The landfill is now closed but is still costing millions to clean up. Bristol’s been on the hook for some of that, but it’s also been one of the most financially stressed cities in Virginia, so the state government has stepped in to help pay some of the costs. The next governor, lieutenant governor and attorney general ought to understand why this is happening.

24. State Street in Bristol

There are lots of good reasons to visit Bristol: the Birthplace of Country Music Museum, multiple music venues, the Hard Rock casino if you’re into that kind of thing. The last time I was in Bristol, I saw the Canadian bluegrass band The Dead South in concert and ate at the Burger Bar, said to be the last place where Hank Williams was seen alive. I ordered the Cold, Cold Heart Burger, which is hot, hot because it’s loaded with jalapenos. State Street — the main drag that goes along the state line — is a curious attraction, too. I’m reminded of the Steve Earle song “Carrie Brown,” where the protagonist has a rivalry with another man for Carrie’s affections:

We met again on State Street

Poor Billy Wise and me

I shot him in Virginia

And he died in Tennessee

That’s the kind of thing that can get you sent to Red Onion. However, here’s another reason statewide candidates should visit State Street: It’s easy to compare the effect of Virginia tax policies with those of Tennessee right across the street. Tennessee has no income tax, but the second-highest sales tax in the country. Different parties are going to see those taxes in different lights, but whatever your views, here’s a chance to do an up-close compare and contrast.

There’s one more reason the two gubernatorial candidates should visit Bristol:

25. A gubernatorial debate in Bristol

There’s been a debate between the candidates for governor in Southwest Virginia for the past three cycles. In 2013, there was one in Blacksburg at Virginia Tech. In 2017, at UVA-Wise. In 2021, at the Appalachian School of Law in Grundy. We’d like to see that tradition continue. This year, Cardinal has partnered with the Appalachian School of Law and PBS Appalachia to propose a gubernatorial debate — to be held in the new PBS Appalachia studio in Bristol.

We formally invited both Democrat Abigail Spanberger and Republican Winsome Earle-Sears shortly after they were confirmed as their parties’ nominees in early April. To date, we have yet to receive a commitment from either. If you’d like to see them debate in Bristol — a debate where we’d like to focus the questions on issues confronting the region — feel free to let them know.

This isn’t meant to be a comprehensive list. And I’m sure there are lots of other places across Virginia that candidates could visit and learn something unique about policy matters. Here’s your chance to tell us, and them, what they are. Fill out this form, and we’ll publish some of the responses.

Want even more politics? We publish a weekly political newsletter, West of the Capital. This week I’ll have a final update on early voting in the primaries, plus other political intel. Sign up below: