On one side of the Danville canal, geese and their goslings mosey through tall grass. On the other side, residents walk their dogs in the shadow of a refurbished textile mill. Right in the middle, turtles swim through its slow-moving waters.

The canal site is the city’s oldest commercial structure, with a history going back about 270 years. It has transformed for different reasons over the years, and its life cycle is not over yet.

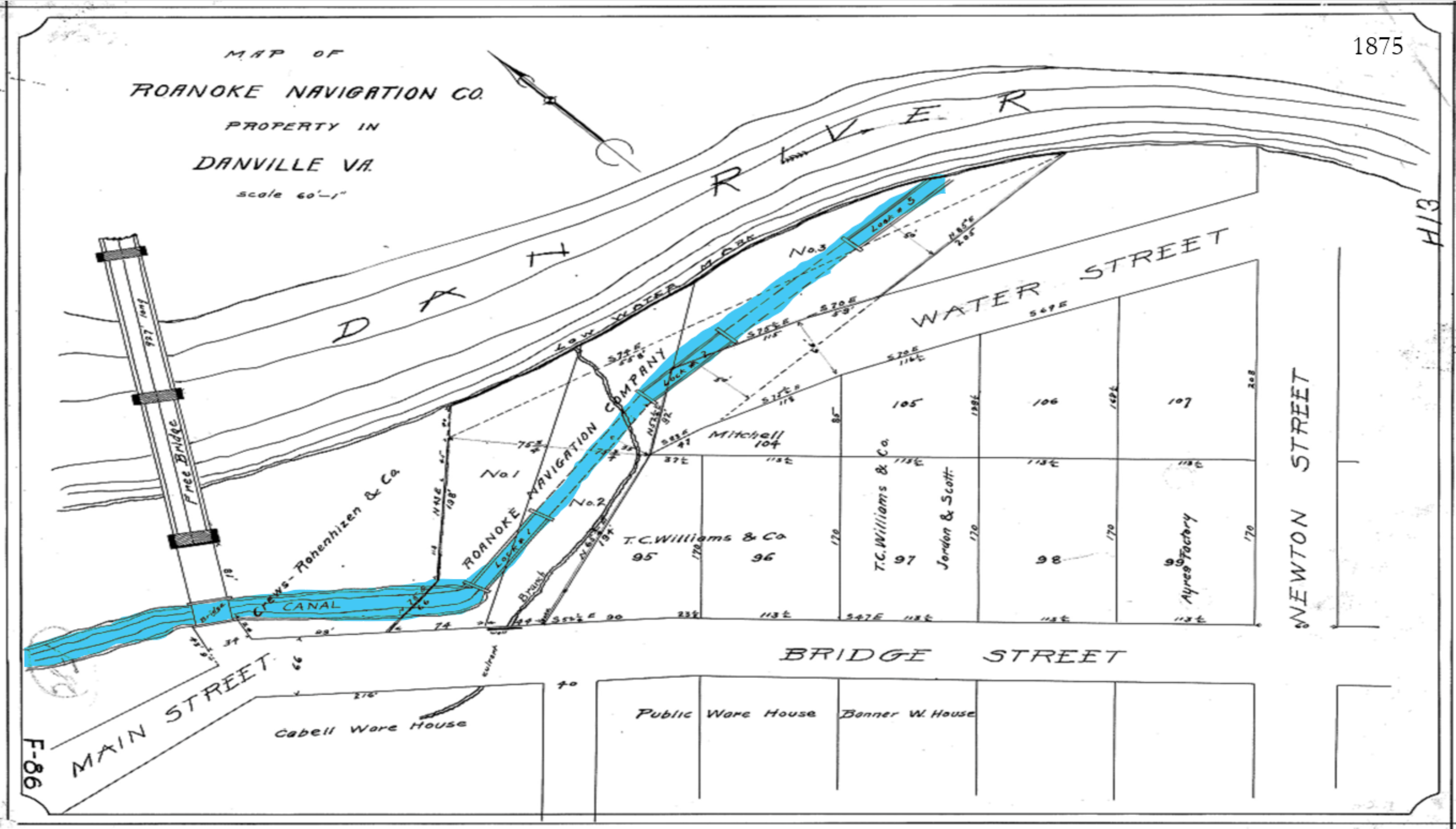

Two centuries ago, the canal was much larger — about three-quarters of a mile long, 18 feet wide and 2.5 feet deep. It expanded over time to about 40 feet wide and 4 to 6 feet deep.

It was used for transportation and power generation. Today, the 1,400 or so feet left of the canal runs in front of the Dan River Falls building.

Soon, the canal may evolve yet again into a recreational feature on the Dan River, reestablishing it as a part of the city’s economy — though in a much different way.

Throughout its lifetime, the canal catalyzed the first joint venture between Virginia and North Carolina after the American Revolution, called the Roanoke Navigation Company. The canal was the subject of lawsuits and lengthy business negotiations. It survived for so long because local businesses relied on it for power.

And eventually, it was almost entirely filled in with pieces of demolished buildings and paved over to create Memorial Drive during Danville’s urban renewal era.

Despite the canal’s previous significance to the city and its future potential, many folks in Danville don’t know its full story, said local historian Jonathan Hackworth.

It’s “something that nobody really talks about,” he said. Hackworth is trying to fix that.

He has submitted an application for a state highway marker dedicated to the canal, which the state Department of Historic Resources will consider at its quarterly meeting Thursday.

If approved, the marker will stand outside Dan River Falls, a former textile mill that has been rehabilitated into a mixed-use development for residential and commercial purposes.

The past: A story across centuries

Many people in Danville assume that the canal was built in the early 1800s by a businessman named Benjamin Cabell, Hackworth said.

Hackworth himself didn’t discover that this was untrue until he started researching the canal to give a presentation about it to a local organization.

“When I started digging into old newspapers, I found that what we thought we knew didn’t really hold water,” he said.

What tipped him off was a newspaper advertisement from 1819 — Cabell’s firm was putting the canal property up for sale. This didn’t make sense to Hackworth, because Cabell had only moved to Danville in 1816.

“That was too short of a timespan,” Hackworth said. “That got me looking. If he built it, how did he do it that fast? If not, what’s really the story?”

Hackworth had to work backwards, tracing property record transfers, ancestry websites and newspaper archives, and visiting the Library of Virginia in Richmond.

His research led him to a 1771 advertisement in the Williamsburg Gazette that offered to lease a tract of land with a gristmill and mill race, a man-made channel that carries water to a mill.

This tract was in the right spot, just where Hackworth knew the canal should be.

Most gristmills in that area of the city were built between 1754 and 1760, which means the construction of this mill race was likely around that time, too. This dates the early formation of the canal site decades earlier than previously thought.

He then began the search for information about how the canal, as we know it today, was built. At the Library of Virginia, he found a chancery court case that mentioned the canal, dating its construction to 1794.

Over the years, the canal was improved to be more suitable for transportation. The Roanoke Navigation Company, a joint effort between Virginia and North Carolina to improve waterways in the region, was responsible for much of this work.

The Dan River crosses the Virginia-North Carolina state line eight times on its 214-mile journey from the Blue Ridge Mountains to Kerr Lake.

The collaboration between the two states speaks to the importance of the canal, Hackworth said, because Virginia and North Carolina had not worked together since they were colonies, fighting the British for independence.

“Virginia and North Carolina had never really gotten along well, but both states realized that unless they started improving their rivers to get goods to the coast easier, they were going to lose out on money,” Hackworth said.

The Roanoke Navigation Company negotiated with Cabell’s firm for about three years, angling for permission to make improvements to the canal.

When negotiations finally concluded in 1821, the company began widening and deepening the canal using enslaved laborers.

Hackworth found evidence of this labor in a report written in 1825, right before the improvements were completed. The report says that “50 of the company’s Negroes are employed on the canal” at this time.

“That is the only documentation that we have about how many slaves were forced to build the canal,” Hackworth said.

After improvements, the canal featured three lower locks that allowed control of the water’s elevation.

Over the next several decades, the Roanoke Navigation Company declined due to flooding that led to costly repairs and the rise of locomotives, which made river travel less popular.

“Then the Civil War hits, which officially brings the company back from the brink,” Hackworth said. “The Northern Army is tearing up railroads, so the South had to utilize the river for transportation. The Civil War artificially kept the company afloat, but when it ended, it wasn’t long before the company folded.”

The Army Corps of Engineers came through Danville during Reconstruction, Hackworth said, and dubbed the canal inoperable, saying it essentially only operated as a dam.

The Union Street dam was built after that, in 1882, and the canal was improved to become a source of power generation. Eventually, textile companies bought up all of the property along the canal.

The canal existed primarily for power generation until 1969, when the city’s urban renewal era began. This involved demolishing more than 60 buildings on lower Main Street, in an effort to modernize the downtown area and bring in more visitors, Hackworth said.

“When they demolished all of those buildings, they took all of the debris and threw it in the canal and packed dirt over top of it and then put a street there and called it Memorial Drive,” he said.

That street, built in 1973, is one of Danville’s main thoroughfares today.

The present and future: A reimagining of the Danville canal

Danville has been working to capitalize on its riverfront in recent years through residential, commercial and recreational projects along the river.

The White Mill, a 550,000-square-foot building that was once a textile mill, has been rehabilitated into mixed-use space that will have 190 apartments and commercial and retail space when complete. The building is now called Dan River Falls.

Between the building and its parking lot runs the Danville canal. A sidewalk stretches along the canal, and a bridge crosses its waters, where Dan River Falls residents can regularly see wildlife.

The building’s parking lot opens up onto Memorial Drive, where cars stream along the pavement that covers what was once the rest of the Danville canal.

Down Memorial, adjacent to Dan River Falls, a riverfront park is under construction. These two riverfront projects will eventually be joined by a third: a whitewater channel created from the remaining canal.

The channel, which is not expected to be complete for several years, will be about 2,000 feet long and used both for recreation and for swift-water rescue training.

The canal’s 1882 headgate system, which controls the flow of water, will allow the water elevation in the channel to be manipulated for both of these purposes.

“The amazing thing is that it’s the oldest commercial structure in Danville and it’s still somewhat functional,” Hackworth said. “When the canal project is done it will be the oldest functioning structure in Danville.”

Preserving history on a changing riverfront

To fit the criteria for a state highway marker, a subject must focus on people or places with regional, state or national significance. It must extend past local impact, Hackworth said.

The Danville canal aided transportation along the river for decades and also did several stints in power generation over the years — certainly making a regional and state impact.

A state marker explaining the history of the canal would have local impact, too, Hackworth said, because most folks in Danville are unfamiliar with the canal’s long, rich lifetime in Danville.

Hackworth said he hopes the marker’s 120-word synopsis of the canal’s history provides a good introduction, prompting people to go look for more information on their own.

If approved, Hackworth’s 85-page application would be pared down to fit on a sign that’s about 42 inches by 40 inches.

To present a more in-depth look at the canal history, Hackworth also gives presentations on his research. His most recent was at the public library at the end of May.

The presentations delve into topics that wouldn’t fit on a historic marker, like estimated transportation expenses for traveling along the Dan River, and how the boats transporting goods, called bateaux, were primarily manned by freed Black men who played dice and arm-wrestled to pass the time on board.

State highway markers are approved in two phases, said Jennifer Loux, manager for DHR’s highway marker program. The first phase approves the marker application itself, and the second approves the exact text.

If Hackworth’s application is approved, the text will be refined and put to a vote at the board’s September meeting.

DHR uses the time between June and September to do additional research, fact-checking and editorial work before finalizing the texts that will appear on the markers, Loux said.

The application is supported by the city’s Industrial Development Authority, which owns this property.

“The canal is an interesting part of Danville’s history and Jonathan has done a tremendous amount of research and spent much time preparing the application,” said Neal Morris, chairman of Danville’s IDA. “I personally think it will be a very informative marker for people visiting the property.”

The riverfront projects around the potential marker site are highly visible developments, Hackworth said.

“That gives us a way to really interpret and tell the complete history that the state marker gives an introduction to,” he said.