Content warning: Some of the historical content in this story includes racial slurs and racist language.

There was a routine to Sundays in the Moore household. A big breakfast and the morning paper, followed by church service.

It was June 1963, and the cool mornings warmed up quickly into long, sticky days.

Eighteen-year-old Dorothy Moore sat with her parents and her sister at the kitchen table of their home in Camp Grove, a historically Black neighborhood in Danville.

Like usual, Dorothy’s father passed around different parts of the daily local newspaper, the big Sunday edition of the Danville Register.

He handed Dorothy and her sister the comics while he and his wife split the other sections.

Dorothy considered her parents to be courageous people. They participated in the city’s civil rights demonstrations that summer, a movement that was mostly made up of teenagers since Black adults in Danville were at risk of losing their jobs.

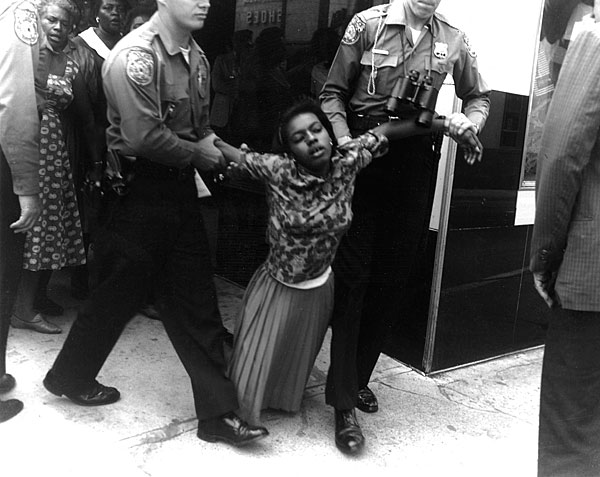

Dorothy can still picture her mother’s long floral skirt draped across the concrete as she lay on the city sidewalks with other Black women, holding signs calling for equal rights.

She remembers they saw each other in passing at the city jail, where they had both been arrested for participating in the demonstrations. Dorothy was being released just as her mother was being escorted inside.

So Mrs. Moore was not the kind of woman who was easily shaken, Dorothy said.

But she still remembers her mother’s gasp at opening her section of the paper that Sunday morning, June 17.

On the front page of the second section, which reported local news, there was Dorothy looking back at her. In a black and white photograph, police officers gripped Dorothy by each arm as they hauled her sagging body, clad in a floral top and pleated skirt, down the street.

“Oh my God, that’s my child,” Dorothy remembers her mother exclaiming.

A newspaper photographer had snapped her picture as she was carried, her knees dragging on the ground, to a police car and taken to jail.

Alongside the photo, the article described “a new technique employed” by demonstrators, going limp to make arrests more difficult without actively resisting.

Dorothy is not named in the article or the photo caption, which only mentions her by saying “a demonstration of the ‘limp’ by young girl.”

The demonstrations were “dwindling,” declared the article only a week after Bloody Monday, the most intense clash of the summer. Dorothy would not remember it that way.

The protests had not remotely slowed down by mid-June, recalls Dorothy, who is now in her 70s and hyphenates her last name as Moore-Batson after marrying her husband Freddie.

But this was typical language for the Register and the Bee, Danville’s daily publications, which characterized the movement as criminal, violent and futile.

Though Dorothy protested every day of that hot, tense summer, and though her photo was published in the Register, no reporter approached her for an interview the entire summer.

* * *

The story of the 1963 civil rights movement in Danville — and how it was met with police violence and challenged by the city government and a segregationist court system — would go largely untold for decades.

Decades, because of an unwillingness to talk about the tumultuous time period. It was shameful for the city, and painful for members of the Black community to recall.

Decades, because the paper of record tried to make it “dwindle” away in the minds of its readers.

“Journalism is the first draft of history,” said Patrick Walters, a journalism historian and professor at Washington and Lee University. “If the first draft of history doesn’t get written, then it’s not surprising that it wouldn’t make it into the history books.”

In 1963, the morning Danville Register and the afternoon Danville Bee were the two editions of the daily newspaper, owned by the same company. They eventually merged into one morning edition, the Danville Register & Bee.

During the first week of protests in early June 1963, not a word about the local movement appeared in either daily newspaper. The hope was that the demonstrations would die out without attention from the press, according to staff at the Danville Historical Society.

The publications misrepresented the movement by characterizing the peaceful protests as out of control, and by placing a heavy emphasis on the arrests and trials that followed. They covered the civil rights movement in other localities and nationally far more often than local activity.

Coverage of the national movement portrayed demonstrations as riotous, and always mentioned when violence occurred, especially toward white people.

Another local paper, a weekly publication called the Commercial Appeal, took a different approach.

“The Commercial Appeal told the truth about what was happening,” said Connie Chaney Carter, who was 15 years old in 1963 when she participated in the movement every day.

Danville’s Black communities would read the Commercial Appeal to get more accurate news about the movement, recalled Chaney Carter, now in her 70s.

This might surprise modern readers who look at archived editions of the Commercial Appeal, which are available online.

It is not a pro-civil rights publication. Compared to today’s standards, the coverage is fair at best — maybe even non-committal — reporting on the movement in a straightforward way and publishing editorials that both celebrated and admonished civil rights activity.

But its reception at the time, and the way it is remembered today, speak to how revolutionary it was in the 1960s South.

“A lot of people didn’t like [the Commercial Appeal], I guess because it told the truth,” said Moore-Batson.

* * *

The first mention of local civil rights activity in the daily papers came on June 6, about a week after the demonstrations began.

Though national news about civil rights was often included on the front page of the morning Register, the first article about Danville’s movement was on page 9. This was the start of the “second section” of the paper, where the local coverage began.

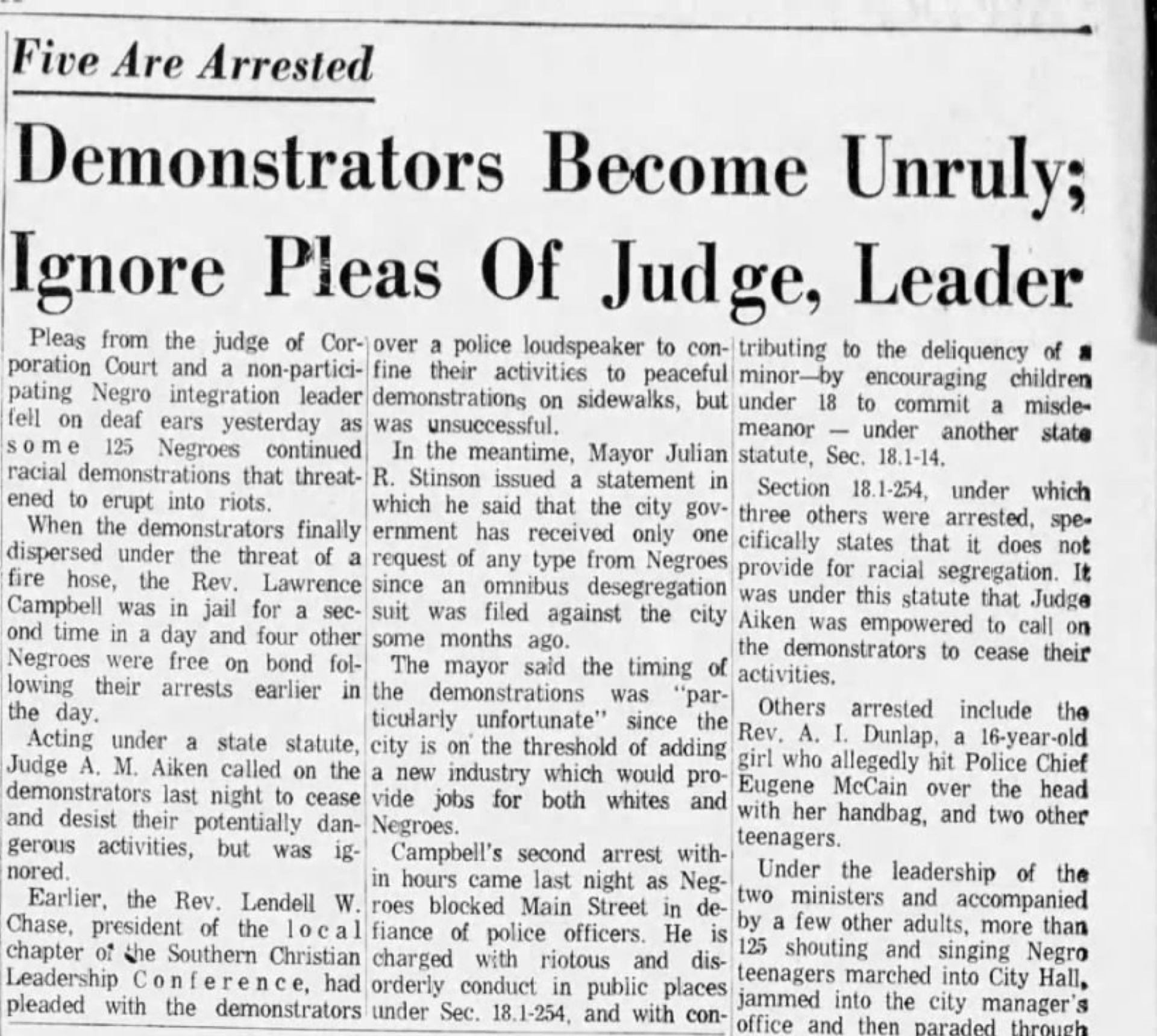

The summer’s first headline about the local civil rights activity read “Demonstrators Become Unruly; Ignore Pleas of Judge, Leader.”

The article described the ongoing protests as disorderly, saying “some 125 Negroes continued racial demonstrations that threatened to erupt into riots.”

The Commercial Appeal’s first article about the local protests appeared in the June 10 issue.

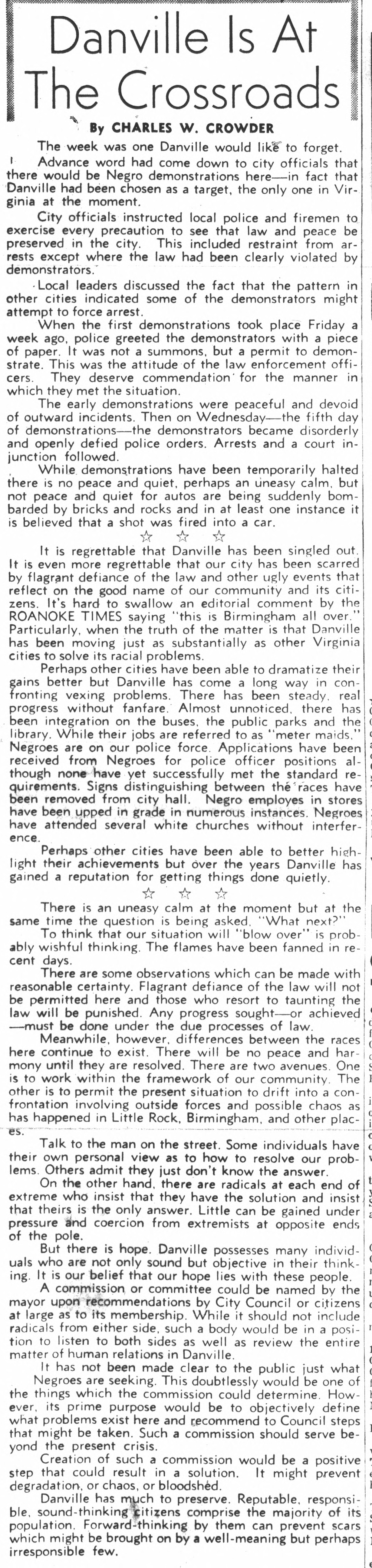

On the front page of the June 10 Commercial Appeal is an editorial by staff writer Charles Crowder, headlined “Danville is at the Crossroads.”

The article is not in open support of the movement, but neither does it discredit it.

It described the first few days of demonstrations as “peaceful and devoid of outward incidents,” consistent with descriptions of the movement from former protesters.

“We were always peaceful,” Moore-Batson said. “[The leaders] had told us that this was a nonviolent movement. And if you can’t be nonviolent, they don’t want you to participate.”

In contrast, the Register and the Bee reported violence on the part of the protesters, saying they carried knives, ice picks and rocks during the marches. No reporter’s name was attached to these stories.

Both the daily publications and the Commercial Appeal reported damage to cars caused by demonstrators and shots fired during the protests. Incorrect, according to former protesters like Moore-Batson and Chaney Carter, who said the demonstrators never participated in violence or caused damage. Movement leaders didn’t condone that, they said.

Still, the Commercial Appeal’s reporting was different enough from the Register’s and the Bee’s that the Black community relied on it for more accurate news about the movement.

Crowder’s editorial ends with a suggestion of forming a committee of community members to “listen to both sides.” It should “serve beyond the present crisis” and would “be a positive step that could result in a solution. It might prevent degradation or chaos or bloodshed,” Crowder wrote.

Meanwhile, the Bee published a statement by a group of white residents criticizing the idea of a committee.

“If the mayor or the council should appoint such a committee, it would be a concession on their part that they had failed,” the published statement said. “From what we have learned of bi-racial committees in other cities, such committees are only used as ‘whipping boys’ by irresolute council members who do not have the courage to assume the responsibilities they have sworn to take.”

The owner of the Commercial Appeal, Charles Womack, was one of the few politicians who was willing to meet with movement leaders and form a committee. Womack, a white city councilman, would face the consequences of his open-mindedness at a council meeting on that very same day, hours after the Commercial Appeal published Crowder’s editorial about the merits of such a group.

But neither the editorial nor the council meeting was the most memorable thing to happen on June 10, 1963.

By the end of the evening, the entire course of the movement would have changed — though Womack didn’t know it yet as he headed to City Hall for the regularly scheduled meeting.

Danville City Council members voted on a variety of mundane items during the meeting, unaware of the chaos that would ensue later that night — a night that would later become known as Bloody Monday.

Read all about it!

- Part II: The Black and The White

- Part III: Two Childhoods

- Part IV: The Unusual Source publishes June 27