Virginia voters made lots of history in Tuesday’s primary election, setting up a general election campaign with lots of “firsts.”

For a long time, one writer after another has proclaimed a “New Dominion” in the “Old Dominion.” That is now quite apparent in Tuesday’s primary victories by Ghazala Hashmi and Jay Jones in the statewide Democratic primaries for lieutenant governor and attorney general, respectively. As the great political analyst Elizabeth Barrett Browning once said in a different context, “let me count the ways.”

1. Not a single straight white male will be on the statewide ballot this fall

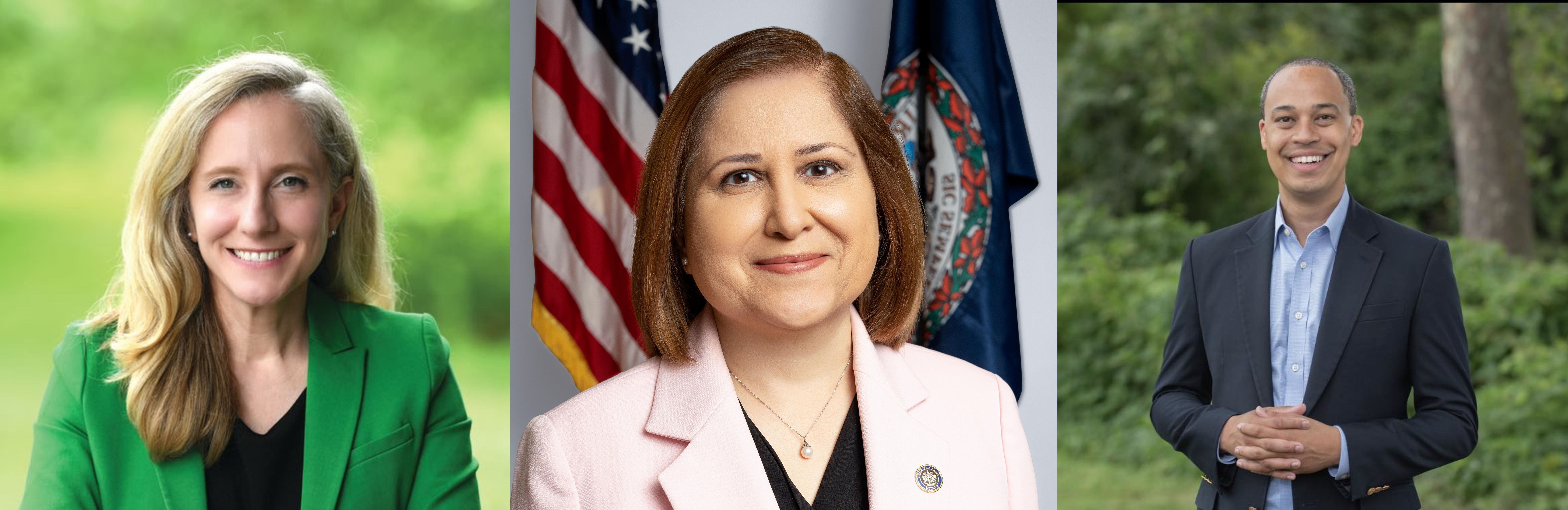

And technically, just one white male, period. Democrats have nominated Abigail Spanberger for governor, Hashmi for lieutenant governor and Jones for attorney general. Republicans have nominated Winsome Earle-Sears for governor, John Reid for lieutenant governor and Jason Miyares for reelection as attorney general.

Reid is the only white male of the six statewide candidates and he’s gay. Miyares, whose mother was Cuban, is Latino. In a year in which Republicans have tried to banish “DEI” — diversity, equity and inclusion — from the national lexicon, both parties in Virginia have nominated their most diverse tickets ever.

We’ll definitely have our first woman as governor. For lieutenant governor, we’ll either have our first Muslim and Indian-American or our first openly gay statewide officeholder. We’ll either have our first Black attorney general or keep our first Hispanic attorney general.

It’s a New Dominion, indeed.

2. Half the statewide candidates are women; that’s a record in Virginia

We already knew we were going to have our first woman as a governor, we just don’t know which one yet. Until now, the most women we’ve had on a statewide ballot at any one time is two — four years ago, Earle-Sears and Hala Ayala competed for lieutenant governor. With Hashmi joining Spanberger on the Democratic ticket, we have a party for the first time in Virginia nominating two women at once for statewide office and, with Earle-Sears on the Republican side, three of the six statewide candidates are women.

Fun fact 1: The first woman nominated by a major party in Virginia for statewide office was Hazel Barger of Roanoke, who was the Republican nominee for lieutenant governor in 1961.

Fun fact 2: The first woman to win a statewide office in Virginia was Democrat Mary Sue Terry of Patrick County, who was elected attorney general in 1985 and reelected in 1989.

3. Two of the statewide candidates are immigrants, another record

Earle-Sears was born in Jamaica; Hashmi in India. And, as noted earlier, Miyares is a second-generation American.

4. Hashmi is the first Muslim nominated for statewide office in Virginia

This is a fact that will likely get more attention nationally than it will here at home, simply because that’s not how we know Hashmi. We know her more as a state senator and a committee chair, at that — the Senate Education and Health Committee.

5. Hashmi’s winning percentage is the lowest of any statewide primary winner in Virginia ever

By the unofficial returns, Hashmi took 27.39% of the vote in a six-way race. Until now, the lowest winning percentage was 32.9%; that’s what Leslie Byrne won with in the 2005 lieutenant governor’s race.

Prediction: This will inspire some to make the case for ranked-choice voting in statewide races.

6. Hashmi won the closest statewide Virginia primary since 1945

Hashmi’s winning margin is 0.75%. That’s the closest of any statewide primary in Virginia since the disputed 1945 Democratic primary that was decided in court. I dealt with that colorful saga in a column last year but here are the highlights: That year saw a three-way Democratic primary between two members of the Harry F. Byrd Sr. “organization” — aka, the Byrd Machine — and an anti-Byrd candidate. The two pro-Byrd candidates nearly tied. Charles Fenwick of Arlington County took 38.3%, Pat Collin of Smyth County 37.8%. That’s a difference of 0.5%. However, there were, shall we say, some discrepancies. Two counties posted inexplicable landslides that were at odds with all their neighbors — Appomattox for Collins, Wise County for Fenwick. Collins went to court to challenge the results, targeting that suspiciously large margin for Fenwick in Wise County. (Fenwick never questioned the suspiciously large margin for Collins in Appomattox County. After all, he was the winner and didn’t need to question anything.) An investigation found poll books in Wise missing — some say “burned.” There were reports that large sums of money had changed hands to “fix” the results in Wise.The judge declared that Wise County was “impregnated with political crooks and ballot thieves” and voided all the votes from the county, which handed the election to Collins.

There are no such allegations of impropriety here. This is simply a close election with a very explainable outcome, which I’ll get to shortly.

7. Jones won the closest attorney general primary in Virginia ever

To be fair, Virginia doesn’t have a long history of competitive primaries. Virginia went through a long period in the 1970s and 1980s in which primaries were out of vogue for both parties. Jones won by a margin of 2 percentage points. Until now, the smallest margin in an attorney general primary in Virginia was the 4.1 percentage points that Donald McEachin won by in the 2001 Democratic primary. Coming in second that year was John Edwards of Roanoke.

8. Richmond’s water crisis likely sank Stoney

Former Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney had contemplated a run for governor. Seeing that Spanberger was so strong, he dropped back to the LG race and began as the frontrunner. He had the most money of any candidate and the endorsement of former Gov. Terry McAuliffe and lots of other well-known Democrats. So how did he lose?

Two ways. One is a more conventional political explanation: Aaron Rouse carried all of Hampton Roads (winning 68.79% in his hometown of Virginia Beach). That deprived Stoney of a lot of Black voters in Hampton Roads, who would have been expected to be part of his base. Once you get outside Hampton Roads, Rouse didn’t win much except in Southwest Virginia while Stoney ran exceptionally strong — with one exception — in communities with large numbers of Black voters. In rural, eastern Southside especially, Stoney racked up the vote, taking 79.29% of the vote in Greensville County, 78.85% in Emporia, 73.88% in Brunswick County. That should have carried him to victory, even with Rouse peeling off Hampton Roads.

It’s that one exception that did Stoney in: his hometown of Richmond. He managed just 20.73% of the vote in the city where he was mayor for eight years. Instead, Hashmi took 58.15% of the vote there. Maybe there are other reasons Richmond Democrats were dissatisfied with Stoney but the city’s water crisis earlier this year — in which the city went nearly a week without water — was surely something that focused their attention. The irony: That water crisis, blamed on a power failure at the city’s water treatment plant, happened after Stoney left office. Still, he got the blame on social media for his administration leaving the plant in such a sorry condition — and on Tuesday, he appeared to have gotten the blame at the ballot box.

If he’d done better in Richmond, he’d have won statewide. He didn’t even need to carry the city, just do better than he did. He lost statewide by 3,597 votes (a margin that might change a bit), but he lost Richmond by 10,509 votes.

9. Utilities haven’t lost this badly since the Henry Howell era

For those who need a refresher, Howell was the populist Democrat who spent much of the 1960s and ’70s crusading against what was then Virginia Power (and today is Dominion Energy, which happens to be one of our donors, but donors have no say in news decisions; see our policy or what I’m about to write).

Utilities are going 0-for-4 so far this year.

Let’s start with the Democratic contest for attorney general. There didn’t seem to be many differences between the two candidates except for this: Taylor took a lot of money from Dominion Energy and Jones took a lot of money from Clean Virginia, often regarded as the anti-Dominion political group. In a close race, anything can be said to have made the difference but that Clean Virginia money vs. Dominion Energy money was such a contrast, it’s hard to avoid drawing the conclusion that this is what tipped the balance in that race.

Now let’s step back further: Clean Virginia is Spanberger’s fifth-biggest donor, at $465,000. Hashmi’s biggest donor is Sonjia Smith at $475,000; Smith is married to the founder of Clean Virginia. We now have a Democratic ticket that’s getting a lot of money from an anti-utility group. Clean Virginia celebrated this Tuesday night by framing this somewhat differently: “For the first time, Virginia voters have selected a full statewide ticket of candidates who refuse contributions from regulated utility monopolies.”

Dominion wasn’t the only utility that lost Tuesday; so did Appalachian Power. In House District 49, Mitchell Cornett started as the underdog for the Republican nomination in a bright red district. He also spent much of his campaign attacking Appalachian Power for its electric rates. In one campaign ad, the Grayson County farmer and county supervisor looked into the camera, wearing a Donald Trump hat while attacking Apco. In that district, that’s pushing two hot-buttons at once. Assuming Cornett wins this fall (and this is a 78% Republican district), the legislators who criticize utilities will gain another voice in Richmond. Henry Howell would be proud.

10. Gov. Glenn Youngkin lost his first race

Until now, Youngkin’s endorsement had been a powerful blessing in Republican nominating contests. It wasn’t Tuesday. When Del. Jed Arnold, R-Smyth County, unexpectedly announced his retirement earlier this year, Youngkin and other top Republicans lined up behind Adam Tolbert, the party’s 9th District Republican chair. What they didn’t count on was Cornett jumping in, and running that spirited anti-utility campaign. This appears to be the first time a Youngkin-endorsed candidate has lost a party nomination. That’s probably not a reflection on Youngkin — this doesn’t seem an anti-Youngkin vote — although Youngkin also didn’t seem to do much for Tolbert. He made no campaign appearances on Tolbert’s behalf, for instance. Lt. Gov. Winsome Earle-Sears did; she campaigned with Tolbert on Tuesday in Smyth County, but by then it was likely too late. Grayson County only accounts for 18% of the voters in the district, but Cornett stirred up his home county to the point where on Tuesday 38% of the votes cast came from Grayson. He then carried Wythe County and that was that; he won with 54.49% of the vote.

Want more politics? Sign up for West of the Capital, our weekly political newsletter? I’ll have more analysis of the primary results.