Content warning: Some of the historical content in this story includes racial slurs and racist language.

The group of Danville City Council members, all white and all men, gathered in the municipal building meeting room, with its high ceilings and dark wooden columns and pew-like bench seating.

Mayor Julian Stinson, a middle-aged man who wore a suit and had his dark, short hair slicked back, presided over the June 10, 1963, meeting, which began ordinarily enough.

The council approved a budget appropriation for a capital improvement project and OK’d the continued operation of city kindergarten classes. It approved another project to acquire property that would allow for the widening of North Ridge Street, and deferred a few other items to a later date.

Then, something more unusual happened: One council member made a motion to censure another.

Councilman John Carter said Charles Womack had debased the city circuit court by meeting with several local civil rights leaders.

The Thursday before, Womack had spent two and a half hours meeting with movement leaders the Rev. Lawrence Campbell, the Rev. L.W. Chase and the Rev. A.I. Dunlap.

The ministers also brought demonstrators Julius Adams, Arthur Pinchback and Harry Wood to help them plead their case. The men were hopeful that the sit-down with city leaders would lead to integration and fair hiring practices.

Most city officials refused to negotiate with movement leaders until the demonstrations stopped.

Womack was the only city leader receptive to such a meeting. He convinced Stinson to attend, and the city manager, city attorney, police chief and fire chief also agreed.

Carter said that Womack’s organization of “the bi-racial committee” had undermined the Danville court, which had issued an injunction against these demonstrations.

Womack had explained his decision in an editorial in that morning’s edition of the Commercial Appeal.

“It is obvious that I was approached on the matter of existing racial differences with the view to a solution,” Womack wrote. “As a duly elected servant of the people, I felt it incumbent upon me to do no less than bring the matter before city council and city officials. I feel that no other responsible city official could have done differently than I did under the circumstances.”

Carter’s censure motion failed to gain a second. Instead, council members adopted a resolution naming the mayor, who referred to demonstrators as “criminals,” as the sole spokesperson for the city when it came to the protests.

This would not be the last time that Womack was targeted for his views and actions on the civil rights movement.

He continued to come under fire for the Commercial Appeal’s reporting.

In addition to the editorials by Charles Crowder and Womack, the June 10 edition of the Commercial Appeal also reported on the indictment of the movement leaders.

It named the leaders, the charges and the bond amounts, saying that “the charges are a result of recent racial demonstrations.”

The reporting does not seem particularly inflammatory. Much of the Commercial Appeal’s coverage of the movement is similarly straightforward.

It was meaningful enough for Black readers to regard it as “the truth” — and for the white community to alienate Womack.

“[The Commercial Appeal] quoted us much better than the Bee,” former protester Dorothy Moore-Batson recalled. “They would print what we actually said. They would interview the ministers leading the movement and actually print what was said.”

Treating the civil rights movement with ordinary respect was a daring thing to do, said Gwyn Mellinger, a professor at James Madison University and an expert on civil-rights era Southern press.

“Regardless of their own feelings, newspaper owners in the South understood that if they treated Black people as if they were normal citizens, a large portion of their readership would feel betrayed,” Mellinger said.

Many of Womack’s friends and peers distanced themselves because of the Commercial Appeal’s coverage, though he gained respect in Danville’s Black communities.

“Mr. Womack, he knew he was welcome wherever,” Moore-Batson said. “We would always see him around High Street [Baptist Church], which was the center of the movement. … At the time, I don’t even remember if I knew his name. I just knew this was a white man who came from the Commercial Appeal.”

Womack’s own support of the movement was the primary reason for the Commercial Appeal’s fair coverage.

A newspaper’s ownership was very important to its journalistic content in the 1960s, said Mellinger. Owners would have been calling the shots about what to cover and how to cover it.

“I haven’t found many cases in this time period … of news reporting that isn’t in lockstep with what’s on the editorial page,” Mellinger said. “What owners did was essentially filter what news was covered, and they may have had strong feelings about race themselves.”

The owner and editor of the Register and the Bee in 1963 was a woman named Elizabeth Stuart Grant, who went by her middle name and inherited the papers at the age of 17 when her father died. She owned and published the Register and Bee for 53 years.

“The speculation is that Stuart Grant just kept out of a lot of things that she didn’t want to cover,” said Joe Scott, former archivist with the Danville Historical Society.

The daily coverage hardly ever mentions the purpose of the movement — the Black community’s effort to end segregation and discrimination.

“They focused on the businesses, the police department, the mayor and the city government, as opposed to printing stuff that happened to us,” Moore-Batson recalled.

Despite the backlash, Womack spent the rest of his council term calling for “racial harmony,” proposing a fair employment practices bill and continuing to publish unbiased coverage about race relations in Danville.

He did not run for reelection in 1966, announcing this decision in an editorial in the Commercial Appeal.

Womack expressed his “personal desire to retire from the political arena” after four years of “attempted intimidation, continued public ridicule, continued attempts to distort my motives, inaccurate news stories and uncalled for tongue-lashings on city council floor…not to mention the possibility of one of the dirtiest campaigns in Danville history as my antagonist seeks to have me defeated.”

* * *

After the city council meeting on June 10, demonstrators gathered outside the jail to hold a prayer vigil for the protesters that had been arrested that day.

A night that began with prayer ended with at least 47 people injured.

The police department deputized municipal workers to help break up the crowd using nightsticks and fire hoses, and this became the first violent clash of the summer.

The next day’s edition of the Bee described a “wild night” and focused primarily on the city’s response to the situation — considering a curfew, calling in state troopers and arresting demonstrators under the injunction that limited protests.

The article also included lengthy descriptions of court proceeding logistics and a list of the names, ages and addresses of over 70 protesters who had been arrested, further characterizing the demonstrations as criminal.

A June 17 article published a similar list of names, this time of demonstrators scheduled to appear in corporation court. The list encompasses almost an entire column of text on the page.

The Bee published photos of fire hoses aimed at protesters with a caption that downplays and justifies the police brutality.

“Some of the demonstrators obviously thought it was fun when their legs were doused with the first sweeps of the hose,” the caption reads. “When the demonstrators didn’t clear out the hose was turned on full force, sending them falling and scrambling between parked cars.”

Because an edition of the Commercial Appeal published the morning of June 10 and the next issue would not be for another week, there was no immediate coverage of Bloody Monday in that publication.

“With a [weekly publication], you lose timeliness,” Mellinger said. “You’re not going to be able to pivot and cover breaking news.”

The Commercial Appeal’s next edition after Bloody Monday was published June 17. It included a front page article that recapped the week of ongoing demonstrations.

The article described a visit to Danville by two national civil rights activists: the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, chief lieutenant to Martin Luther King Jr., and William Kuntsler, an American Civil Liberties Union lawyer.

This article included viewpoints and quotes from the national activists, voicing their encouragement to Danville’s protesters.

The Register and the Bee covered Walker and Kuntsler’s visit, but did not quote their support of the local movement. The daily papers rarely quoted even the local civil rights leaders.

“I cannot remember them [Register and Bee reporters] interviewing anyone,” Moore-Batson said. “You would just see them snapping pictures with their little notebooks in front of them, writing this and that, but I never saw them talk with anyone.”

Instead, the Register and the Bee deferred to police chief Eugene McCain, the mayor and other city officials for information.

This was a common journalism practice at the time, said Patrick Walters, a journalism historian.

“One of the things that journalists have relied on for so long is tilting towards and favoring official sources much more than quote-unquote non-official sources,” Walters said. “The longtime journalistic perspective is, ‘We’ve got to rely on the police, we’ve got to talk to the elected person.’”

Published quotes supporting the movement were subversive for the time.

“‘I think everything you have done is lawful and legal. … Keep doing the demonstrating. Keep going on,’” the ACLU’s Kuntsler said in the June 17 Commercial Appeal.

The article also reported that Kuntsler planned to “ask for a federal court injunction to halt alleged police brutality.”

The June 17 edition of the Commercial Appeal detailed charges and the trial process, though without publishing the names and addresses of those arrested, as seen in the daily publications.

On many days, articles about the ongoing court cases made the front page of the Register or the Bee rather than coverage of the demonstrations themselves. Front page headlines reported “Corporation Court List has 205 Cases,” “Court Actions and Conferences Come in Wake of Race Trouble,” and “New Demonstrations Not Held; Court Actions Continue.”

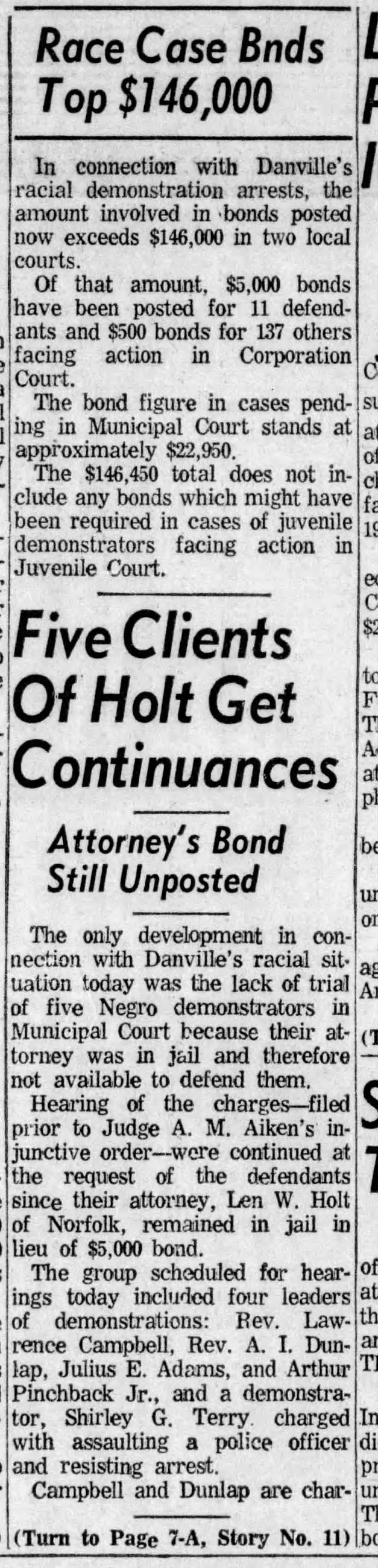

Smaller articles kept track of total bond amounts for arrested demonstrators and the outcomes of specific trials.

The Register and the Bee published editorials praising the segregationist judge who presided over the trials, Judge Archibald Aiken, and a statement in his support written by the Danville Bar Association.

Meanwhile, over the course of the entire summer, there is not a single front page article in the Commercial Appeal that mentions local court cases in its headline.

There, front page headlines said “City Remains Quiet as Negroes Mass March and Rally Wednesday,” “Hope Rises with Meeting on Racial Crisis Here” and “City Streets are Quiet but Racial Developments Unfold Behind Scenes.”

By mid-June just a few weeks after the demonstrations began, the Register and the Bee described the movement as petering out. Moore-Batson and fellow protesters like Connie Chaney Carter recall daily, well-attended protests throughout the summer.

“Demonstrations which had kept Danville in the grip of racial unrest seem to be weakening today as only a few demonstrators showed up for a scheduled mass meeting,” reported a June 15 article in the Bee.

“Things didn’t really die down until after the March on Washington” in August of that summer, Moore-Batson said. “On June 15, things were still heating up.”

Womack would come under more fire as the summer went on, the fallout reaching his family of seven. Black residents would continue to rely on the Commercial Appeal for their news about the movement. And the Register and the Bee would continue to mischaracterize it.

Read all about it!

- Part I: At the Crossroads

- Part II: The Black and The White

- Part III: Two Childhoods

- Part IV: The Unusual Source publishes June 27