Pharmacy closures and transportation barriers are making it harder for Virginians, especially those in rural communities, to access health care. On Wednesday, staff with the Joint Commission on Health Care presented preliminary findings from two studies that could shape policy discussions in next year’s General Assembly session.

State studies on pharmacy deserts and medical access

Written comments are open through June 27.

Comments can be emailed to jchcpubliccomments@jchc.virginia.gov or mailed to 441 E. Franklin St., Suite 505, Richmond, VA 23219.

The studies focused on pharmacy deserts and the challenges Virginians face getting to medical appointments. Researchers drew on state data as well as on insights from interviews with pharmacists and community leaders. Now, they’re inviting the public to weigh in through June 27.

Public comment periods are important as they help ensure policy recommendations are also based on real-world experiences. Personal perspectives help illustrate how distance to pharmacies and lack of transportation impact people and the communities they live in.

“It will be important to understand the impact of pharmacy closures, not just in areas that are already pharmacy deserts but also to understand the needs of the communities that are experiencing pharmacy closure,” said Estella Obi-Tabot, senior health policy analyst with the state commission.

This will help policymakers develop strategies to prevent pharmacy deserts from happening, she added.

A declining number of pharmacies

Virginia is feeling the national trend of pharmacy closures. Major chains like Walgreens and Rite Aid have shuttered nearly 2,000 locations nationwide as part of restructuring efforts, with some of the closures hitting Virginia. Independent pharmacies are also struggling. Low Medicaid reimbursement rates and dispensing fees can leave small businesses footing part of the bill for prescriptions filled for Medicaid patients.

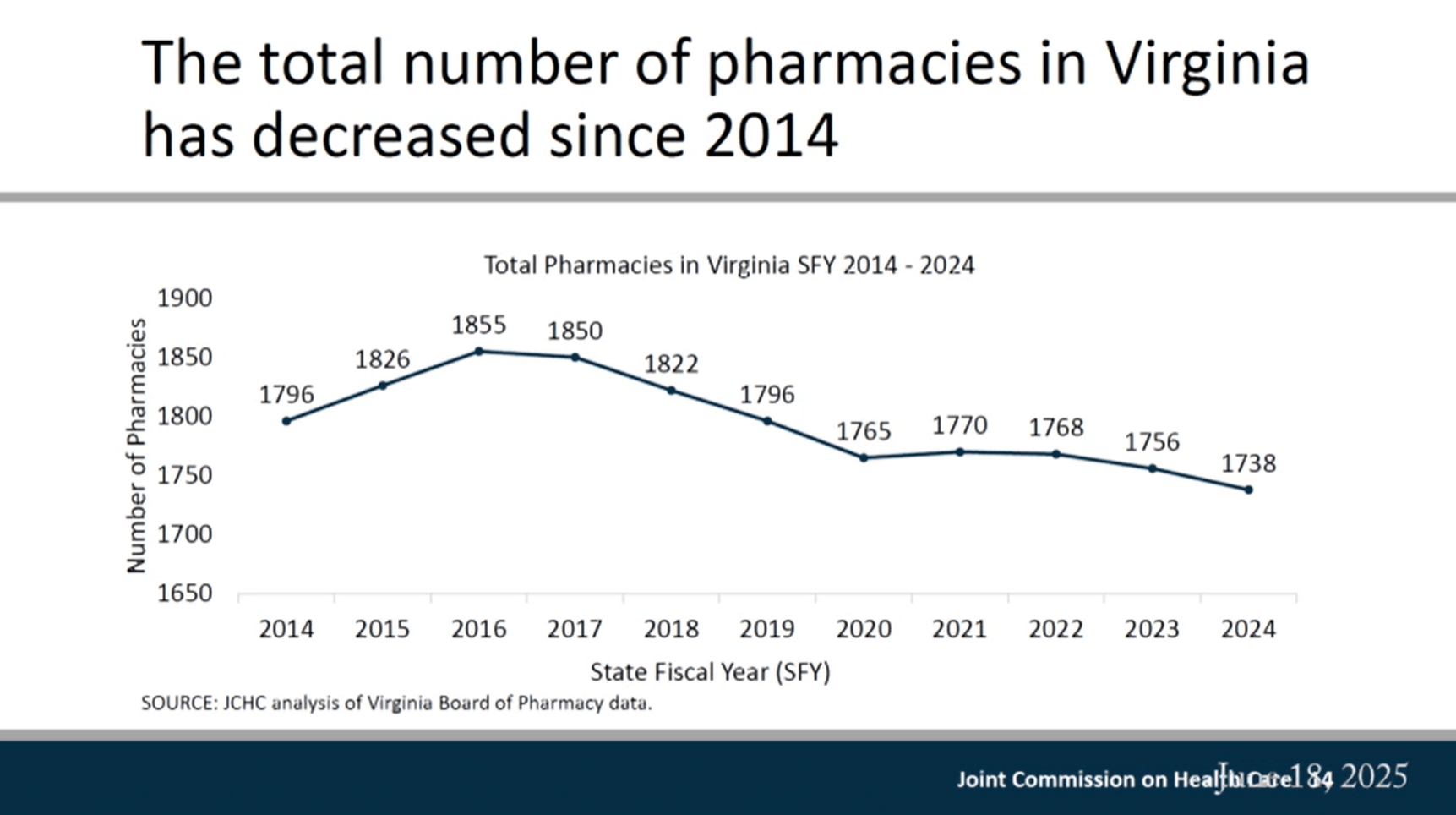

In 2024 alone, 50 pharmacies closed across the commonwealth, according to data from the Virginia Board of Pharmacy.

In response, state lawmakers initiated a study late last year to assess pharmacy deserts, identify the factors limiting access to these essential services and recommend strategies to protect and expand that access.

The early data confirms the concern: The number of pharmacies in Virginia is declining.

From 2016 to 2024, Virginia lost 6% of its pharmacies. That picture varies across the state, as 36 localities saw no change in pharmacy numbers and 30 experienced growth, while 61 localities lost pharmacies. Of those that lost pharmacies, 25 localities saw numbers drop by 25% or more. This includes Dickenson and Patrick counties.

At the end of 2024, 51 small community areas across 28 localities met the definition of a pharmacy desert, where the distance to a pharmacy was more than 1, 5 or 10 miles for areas designated as urban, suburban and rural, respectively, and where 20% of residents live below the federal poverty level. Southwest and Southside counties with pharmacy deserts include Wise, Grayson, Floyd, Halifax, Charlotte and Bath. Some counties — including Carroll, Alleghany, Botetourt, Rockbridge and Nelson — not only qualify as pharmacy deserts but also saw pharmacy numbers decrease by 25% or more.

Not every locality that has seen heightened closures is also designated as a pharmacy desert, and that’s important to note, according to Obi-Tabot.

“Pharmacy closures have negative impacts on people and their communities whether it’s defined as a pharmacy desert or not,” she said.

Pharmacies do more than fill prescriptions. They provide immunizations, medication counseling and help patients avoid harmful drug interactions. When pharmacies close, patients — especially those managing chronic conditions, living in rural areas or facing financial hardship — are more likely to miss medications and need expensive emergency department visits, Obi-Tabot said.

Transportation barriers compound access problems

Getting to care is another challenge. In 2020, about 6% of Virginia households lacked a vehicle, according to the Department of Rail and Public Transit. In Southwest Virginia, that figure was closer to 7%.

Without reliable transportation, patients are more likely to miss appointments, skip medications or delay needed care, all of which can lead to more emergency room visits and hospitalizations or even increased risk of death, said Emily Atkinson, associate health policy analyst with the commission.

Patients who need frequent care, such as dialysis or other treatments, face the steepest hurdles. Rural hospital closures have only made things worse, forcing people to travel farther for essential services. And for low-income families, the cost of owning a car or paying for public transit — if it’s available — can be out of reach.

Urban areas offer services such as paratransit, a form of public transportation for people with disabilities who can’t access regular bus or rail services. But many rural parts of the state lack any public transportation at all. Without access to a personal vehicle, residents in these communities have few options for getting to medical appointments.

When neither public transit nor personal vehicles are available, some people resort to using non-emergency EMS services to reach care, said Del. Bobby Orrock, R-Spotsylvania County.

“It’s an example of impacts in other areas that result from a lack of transit,” said Sarah Stanton, executive director of the commission. She added that the commission will have more information on this particular impact in the final report in October.

Virginia does have two state-funded programs that serve residents with transportation barriers: the Medicaid Non-emergency Transportation Program and the Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities Program.

The Department of Medical Assistance Services contracts with a company called ModivCare to provide federally required medical transportation services for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Navigating these services can be difficult, Atkinson said. Eligibility rules, mileage limits and other restrictions often prevent patients from using transportation programs. Even when eligible, patients may find that the available services can’t meet their needs, particularly for recurring appointments or specialty care that requires specialized vehicles.

“A major theme that arose in most interviews JCHC staff conducted was the intense demand for transportation services as well as transportation providers’ inability to keep up with that demand,” Atkinson said.

Rising operation costs without additional funding make it impossible for many programs to expand. Without more resources, transportation providers struggle to hire full-time drivers or offer competitive wages, making it harder to recruit and retain staff.

The commission’s final report will present policy options and evaluate the two state programs. It will also include feedback from stakeholders and patients to assess how well these services are working and where improvements are most needed.