Content warning: Some of the historical content in this story includes racial slurs and racist language.

David Womack was told to avoid downtown Danville during the summer of 1963.

His parents instructed him to stay away, he recalls, though countless other kids his age were there daily — and the only difference between them and David was the color of their skin.

He knew they were participating in civil rights demonstrations, but he was 14 years old and it was summertime.

“I knew there were things going on that were impactful, but at first, I had other priorities in my life at the time,” David said, looking back on that summer 62 years ago.

But the demonstrations began to feel very real to David when he saw how much his father cared about them — and how their family was treated as a result.

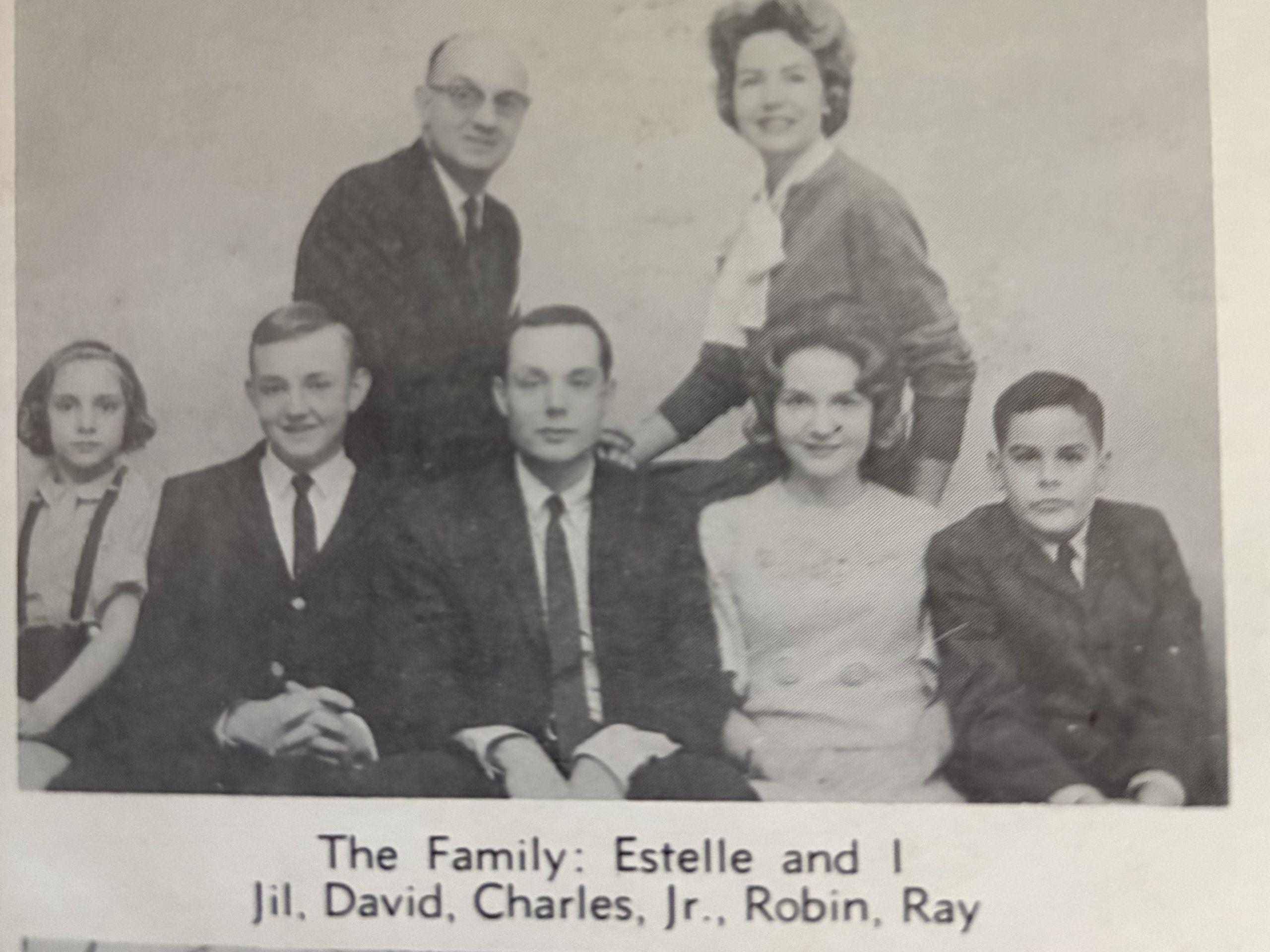

A white city councilman and the owner of a local newspaper, Charles Womack was an unlikely supporter of the movement.

David remembers reading the Commercial Appeal, as well as the daily publications, the Danville Register and the Danville Bee, on a regular basis.

“[The Register and Bee] had the best sports section,” David said. “I didn’t read the editorials, but I would certainly scan the local news section to see what was going on.”

He also heard about the movement from his father, though Charles never talked to his five children about it directly.

“I overheard a conversation between him and my mother,” David recalls. It was early June, and his father had returned home late, visibly rattled, after witnessing the demonstrations.

What bothered him was not the protest itself, David said, but the response to it.

“I remember how shook up my dad was,” David said. “I remember him coming back just unbelievably shaken…I vividly remember him saying that [white] people were walking around with knives, saying ‘I’m going to stick me a [n-word] tonight.’ He was extremely shaken by that.”

“The offshoot for him was that he lost just about every friend he had in the city of Danville,” David said. “Everybody in town knew who he was and what side he was on, there’s no question about that.”

Charles’ friends on the church boards and in the bridge club no longer wanted to be associated with him, David said.

“They didn’t want to maintain a close friendship or interact with him on a social or business level. People would ask them, ‘Why are you still such good friends with Charlie Womack?’” David said. “I remember an occasion where he went to a function at the country club and just came back really despondent…It wasn’t a comfortable event for him.”

A June 8 article in the Danville Register described Charles as an “instigator” of the movement, because of his meetings with local activists.

An August 19 article, also in the Register, detailed a council meeting where Charles made a motion to form a committee to assess the ongoing conflicts in Danville. Failing to do so would sully the city’s reputation, Womack said.

“Womack exploded an otherwise smooth business session” to suggest this, the article said.

The article quoted Councilman John Carter, who often disagreed with and disparaged Charles, saying:

“‘He speaks of giving Danville a black eye,’ Carter declared. ‘I ask you, what could give Danville more of a black eye than to sit down with the Negroes [leading the movement?]”

David remembers other family members asking his mother and father how they could stand to stay in Danville with the way they were treated.

“But he had a lot of determination about it,” David said. “And my mother never said, ‘Charlie, this isn’t good for us socially,’ or anything like that. She wasn’t a social butterfly, so that wasn’t important to her. She supported him and never did anything to deter him.”

It wasn’t until David was older that he realized how much courage it took for his father to publish an alternative narrative about the civil rights movement, when the daily papers of record at the time were working to discredit and misrepresent the demonstrations.

There wasn’t one “aha moment,” David said. But as the years went on, he would hear from folks in the community about their respect for his father that they were too afraid to express at the time, he said.

David worked for the Commercial Appeal himself one summer when he was in college, after his older brother had bought the paper from their father.

He helped with newspaper delivery and liaised with advertisers, some of whom advertised with the Commercial Appeal simply because they wanted to support Charles.

“My sense was that they never really felt like the advertising dollar was well spent [on the Commercial Appeal] because it was a weekly paper,” David said. “But I think they wanted to give us the business because of my father and the esteem they held him in, and to keep another voice in the community.”

Eventually, many Danville residents held Charles in high regard, as do today’s local historians. His obituary described him as “actively involved in promoting racial harmony during the early 1960s.”

One memory about these changed feelings toward the Womack family sticks out, and still makes David emotional.

The night after Charles died in 2005, a Danville politician who worked with Judge Archibald Aiken to criminalize the movement visited David’s house, he said.

“He had a walker and his daughter was helping him up the steps of our home. He told me who he was and I invited him in,” David remembered. “He said, ‘No, I can’t come in, but I wanted to come by and tell your family that your father was right.’”

David doesn’t know exactly why his father felt so differently than other Danville leaders about the movement, he said.

“I’ve thought about that an awful lot since,” he said. “He grew up in Martinsville, but his father, my grandfather, was a very enlightened individual, an entrepreneur and a clear thinker.”

David remembers the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, and how some folks were concerned that schools would not have enough supplies for each student after integration. His grandfather asked him, “Which little Black boy are you going to share your desk with today?”

“They were both very openminded,” David said. “And he knew the Commercial Appeal was never going to make a lot of money as a weekly paper, but he pursued that as a labor of love…He wanted to have another voice in the community.”

Having that alternative account of the protests made a huge difference in the community, former protesters say.

“Whether he got the story correct or not is possibly debatable,” David said. “But there’s no question that the Register & Bee didn’t get it right. No question about that. I think my dad tried his best to get it right.”

* * *

Andrea Burney knew where to find the news about her community in the paper. She had to flip to the back of Danville’s weekly publication to find the section called “Faces and Places,” which had been renamed from simply “Colored News.”

In addition to Faces and Places, the Commercial Appeal also had news from individual Black communities like the Schoolfield neighborhood, Andrea said.

“We didn’t have the internet, so it was our only real vehicle for news,” Andrea said.

This was especially true because there were no local Black-owned newspapers in Danville at the time.

“We had a number of non-local African American newspapers, like the Afro-American out of Richmond,” Andrea said. “They covered basically the state of Virginia, and you could submit information.”

But consistent local Black news had to be found in the Commercial Appeal.

Gwyn Mellinger, expert on civil rights-era press, said she’s never heard of a white-owned paper covering local Black news during this time period.

The publication had a reputation for “more accurately reporting the Black news,” said Karice Luck-Brimmer, a local Black historian in Danville.

“In the Register & Bee, you didn’t really get much of the Black news. That was by design,” Luck-Brimmer said.

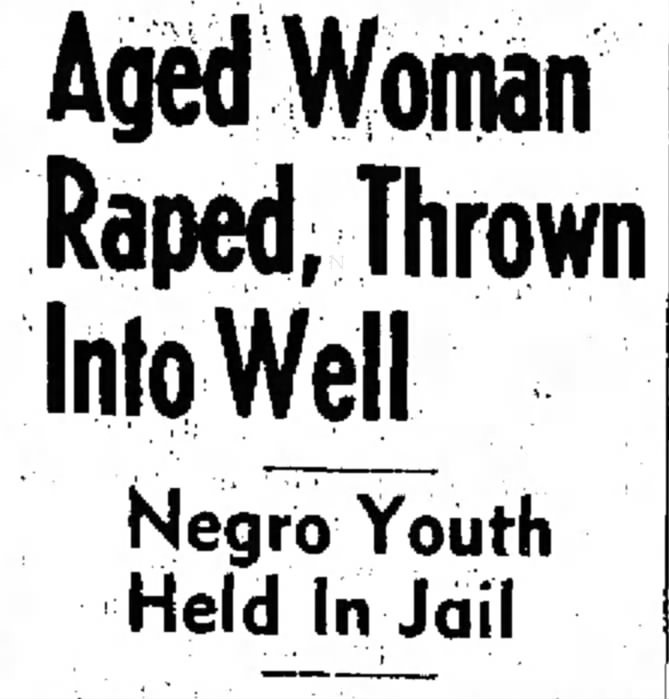

Though there was no coverage of local Black communities, the Register and the Bee regularly reported on Black people in other localities, both near and far, most often when they were accused of crimes.

The Register reported about an incident in Kansas City, Mo., on July 7, 1963, under a headline that read, “Negro Prowlers Sweep Through Park, Attacking Groups of Young Persons.”

A headline on June 29 read “Aged Woman Raped, Thrown Into Well: Negro Youth Held In Jail.” The story came from Dillwyn, Va., over 100 miles from Danville.

A July 6 headline reported “Negro Man Kills Two, Wounds Trio: Reportedly Takes Girl Hostage,” a story from Linden, N.J.

This kind of coverage was typical for the time period and geographic location, and it made white readers more likely to fear the local Black population, Mellinger said.

“In the South, newspapers that were owned and staffed by white people understood that the reader did not want to read about Black people, unless they were criminals, unless it was proving stereotypes, that sort of thing,” she said.

This fear was aided by the language the Register and the Bee used around the civil rights activity, which characterized the movement as dangerous as well.

The Register used the adjective “militant” to describe the Danville Christian Progressive Association, a local affiliate of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s organization.

Coverage often described the movement’s participants as “a highly vocal minority,” and portrayed most of the local Black community as passive and “respectable” until stirred up by outside “unamerican agitators.”

By this standard, the Commercial Appeal was “very progressive for its time,” Luck-Brimmer said.

It had Black reporters on staff as early as 1947 to report the Black news, which would have been very uncommon.

Andrea’s father George became the Faces and Places reporter for the Commercial Appeal when she was seven months old in 1954.

This was about a decade before Danville’s civil rights movement, and two decades before the other local publications, the Danville Register and the Danville Bee, hired Black reporters.

Andrea herself was the Register’s first Black reporter in 1975.

George had left the Commercial Appeal and returned to his teaching job by 1963, when Danville’s civil rights movement was in full swing. And at about 9 years old, Andrea was too young to protest.

But she remembers growing up in segregated Danville and how important the Commercial Appeal was to her community during that time.

“We depended on [the Commercial Appeal] as a community newspaper,” Luck-Brimmer said. “Even though it was founded by white people, it was part of the community.”

As Andrea pursued her own career in journalism, she caught a glimpse of what her father experienced as one of the city’s few Black reporters.

Twenty years later, she was still one of the city’s few Black reporters, though the Register and Bee included more local Black news by that time.

“I didn’t only cover Black news, but I did cover a lot of Black news,” Andrea said.

She remembers certain places in Danville and Pittsylvania County where she was reluctant to go as a Black reporter while working at the Register.

“I had to cover all different kinds of events, and I would get called the n-word,” Andrea said. “People would say we don’t want n-words here…. I’m sure my father experienced that as well. But he didn’t talk about it.”

Read all about it!

- Part I: At the Crossroads

- Part II: The Black and The White

- Part III: Two Childhoods

- Part IV: The Unusual Source publishes June 27