The calendar that hung on the wall in Sherry Smith’s water-damaged trailer read February. It unceremoniously marked the time when life inside the mobile home stopped for her and her husband, Mike Smith.

It had been more than three months since winter storms brought widespread flooding across Southwest Virginia and about three feet of water into the Smiths’ home. They haven’t been able to move back into their trailer since then.

Instead, the Smiths are staying with in-laws after they spent a few weeks in different motels and makeshift community shelters. They are on a fixed income and can’t afford to replace the home that Sherry had owned for more than two decades. The February flood left them homeless.

“I never dreamed I’d miss home like I do. I can’t sit down, watch TV like I want to. They’re good to me,” she said of her in-laws, “But I can’t just get up and do stuff like I want to, it’s not my home. I want my home.”

Many of their neighbors, in the trailer park on Orange Street in downtown Richlands, have also been displaced. Or they have remained in water-damaged mobile homes without anywhere else to go.

Richlands is a small coal town with waterways that run through it, connected to the Clinch River. One official described the town as being “surrounded by the Clinch.” About 150 homes, many in low-income neighborhoods, in a town with a population of roughly 5,000, were affected by the February storm. Sub-zero temperatures hit the region a week later and caused floodwater to freeze in some homes, Chief Ron Holt said. Holt doubles as the Richlands town manager and the local police chief.

The February flood was the fourth major flooding event to hit the Southwest region since summer 2021.

After the widespread devastation, it took the Federal Emergency Management Agency nearly two months to approve a disaster declaration for the area, along with public assistance to help rebuild local infrastructure.

West Virginia, which borders Tazewell County where Richlands is located, received a disaster declaration and approval for individual assistance roughly one week after the storm moved through Appalachia.

When the disaster declaration was approved for Virginia, it was for public assistance to help rebuild infrastructure in damaged localities. Individual assistance, meant to help people rebuild or repair homes or relocate to new ones, was not approved. That fact has left many in the town of Richlands feeling overlooked and wondering why.

The answer lies in a formula used by the federal agency to determine whether a state would qualify for assistance, and what kind of assistance, after a disaster. That formula directly disadvantages the more rural, more impoverished — and more disaster-prone — parts of Virginia.

Six components, two factors: how individual assistance is harder to get in SWVA

FEMA has two main buckets of funding to help with disaster recovery, once a declaration has been approved: public assistance and individual assistance.

Public assistance can be put toward rebuilding and repairing roads, bridges and infrastructure — things that would be owned by the locality or the state. After a disaster, state agencies are deployed to collect an initial damage assessment to submit an application for aid to FEMA. Every state has an economic threshold to meet to receive public assistance. Once that threshold is met, it’s only a matter of time before funds start to flow into an affected locality.

Individual assistance, which can go toward rebuilding and repairing individual homes, is a bit more complicated.

The formula used by FEMA to determine whether a state or territory qualifies for individual assistance takes six different factors into consideration, an agency spokesperson said. Those six components include two principal factors: the state or territory’s fiscal capacity and resource availability, and the total uninsured home and personal property losses experienced due to a disaster.

The federal agency assigns a value that it believes Virginia is worth, as far as its economic resource availability, said Rob Ward, Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s Chief Transformation Officer. Ward has been working with the White House on disaster aid for Southwest Virginia.

Property values from across the state, including the more affluent parts, are used in the formula to determine when Virginia can qualify for individual assistance. The inclusion of those homes with high property value has caused the threshold for individual assistance to rise across the entire commonwealth.

“The challenge that we run into is that because there are parts of Virginia, Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads and other areas that tend to be wealthier and have more income, that formula disproportionately impacts less affluent parts of the state,” Ward added.

The threshold for individual assistance to be approved in places like Southwest Virginia is higher than in neighboring states of West Virginia and Kentucky. The financial metrics work in their favor in those states because the statewide property value is lower.

Of the last seven disaster declarations to be issued by FEMA in Virginia, between 2021 and 2025, five were floods that hit the Southwest part of the state. The other two were winter storms that affected Virginia’s Southside and Central regions.

High-cost, high-property value homes from other parts of the state have disadvantaged people in Southwest Virginia, where the average home cost and property value are much lower, in their effort to qualify for individual aid through FEMA.

West Virginia and Kentucky qualified for individual assistance, why not Southwest Virginia?

A state’s fiscal capacity is a principal factor for considering the need for FEMA’s individual and housing assistance program.

That fiscal capacity indicates a state’s ability to manage disaster response and recovery by considering its means to raise revenue to respond and recover following a disaster. Factors used to determine a state’s fiscal capacity include the state’s total taxable resources or gross domestic product and per capita personal income, along with other factors, according to a March report by the Congressional Research Service.

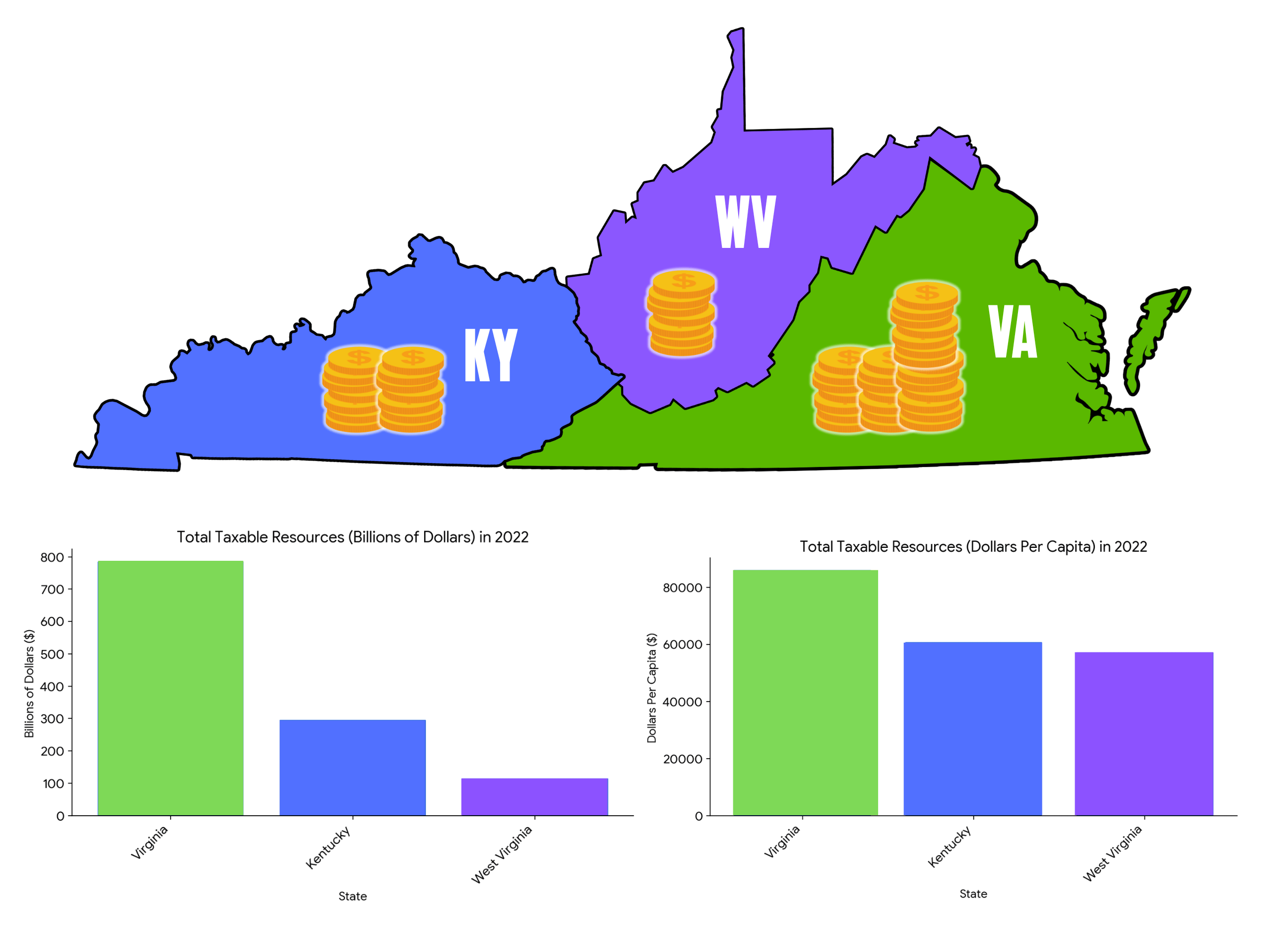

Virginia’s total taxable resources were estimated at $785.2 billion in 2022, while West Virginia’s were estimated at $114.2 billion and Kentucky’s were estimated at $295.8 billion that same year, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Virginia’s dollars per capita, or the average per person, was estimated at $90,476 in 2022, while the dollars per capita in West Virginia and Kentucky were among the lowest in the country, at $64,393 and $65,565, respectively, that same year.

Because Virginia’s total taxable resources and per capita income are higher than both West Virginia and Kentucky, Virginia has a higher threshold to meet than its neighbors to the west before residents are able to receive individual assistance from FEMA. And that includes Southwest Virginia’s vulnerable residents.

The maximum amount a household could receive in individual assistance to rebuild or repair their home is set at $43,600 for fiscal year 2025, according to the Federal Register. That amount could go a long way in helping people in Southwest Virginia’s impoverished communities to recover, if Virginia had qualified for individual assistance following the February floods.

The cost to completely replace a single-section home with two bedrooms and two bathrooms would be around $85,000, said Randy Grumbine, executive director of the Virginia Manufactured and Modular Housing Association.

A used 14-foot by 66-foot mobile home in Tazewell County was recently listed on MH Village for $33,000.

“We’ve seen it before, back with the Hurley floods and then the White Wood floods, we did not receive individual assistance. And yet, right across in West Virginia, or right across in Kentucky, they do, and it has to do with the fact that the formulas work against Virginia,” Youngkin said during a visit to Southwest Virginia in April.

Youngkin was appointed that month to a council, formed by President Donald Trump in January, that has been charged with reviewing FEMA’s existing ability to “capably and impartially address disasters.” The council’s first meeting took place in May.

“What we hope to do going forward here is to work with FEMA to see if there’s a way to evaluate those things on a more regional basis because we have people in these communities that can see West Virginia and can throw a rock to West Virginia or Kentucky and those folks are receiving the benefit but the folks in Virginia, just across the line, are not,” Ward said.

In the meantime, the Virginia General Assembly has taken steps to attempt to fill the gaps without help from the federal agency, though the state lacks a standing fund for disaster recovery.

The General Assembly included $50 million in the budget amendments packages during the 2025 session to provide funding to recover and rebuild for residents who were affected by Hurricane Helene and the February floods. That $50 million will be split up into two categories: $25 million for recovery and rebuilding for home and business owners, and $25 million for mitigation efforts to rebuild flood-stricken communities to be more resilient to those kinds of disasters.

No money had been put aside for disaster recovery despite the state’s relative wealth, before the storm, nor was any such standing fund created by the state during the 2025 General Assembly session to protect against future disasters after the $50 million is tapped out.

Months after disaster struck, still no aid

Youngkin signed the budget amendments package on May 2. Richlands officials received word that the application process to receive flood assistance opened on June 23, nearly two months later.

The $50 million included in that package is an effort to fill the gaps where funds are still needed to rebuild and recover, like in the town of Richlands.

Laura Mollo, a Richlands town council member, said she started to receive regular calls from residents affected by the February storm asking when they would be able to receive state assistance after the legislation was signed.

“I have a group of four, five ladies who call me every week like clockwork to say, ‘Have we missed it? When’s the funding coming?’” she said.

Residents are concerned that $25 million slated for home and business owners may not stretch far enough to fund recovery and rebuilding for everyone in need, following the two disasters.

Henrietta Johnson is one of those people.

“I kinda heard that it might be like first come, first served,” Johnson, 67, said.

She has lived down the street from the Smiths, in the same trailer park, for about two years. Floodwater ripped her back porch off of her trailer, and about nine inches of water swept through her home on her birthday.

“It sure made a mess,” she said. “I cleaned up mud for a week.”

Johnson is living in her trailer now, but she suspects mold may be growing under her floorboards. The Red Cross and United Way helped her to replace her water heater, dryer and refrigerator after the flood, but she hasn’t been able to receive other help.

“My insulation is probably ruined and the floor in my house is probably ruined,” she said.

The first repair that she would make, if she had the resources, would be to rebuild her back porch, she said. The back door sits right next to her bedroom, and Johnson, who walks with a cane, is concerned she would not be able to make it to the front door in time if there were a fire. She was able to evacuate her home on the night of the flood with the help of a police officer who carried her, piggyback, to higher ground.

“Those are the only three things I want fixed, is flooring, insulation and my porch,” she said.

The total cost of those three items is hard to come by, but Grumbine estimated that it could be between $13,000 and $16,000.

“It’s hard to say for sure because the way the homes are built, the first thing that goes down is the subfloor, so if you can just cut out the old floors and leave the floors in place, that’s a heck of a lot cheaper,” he said.

The cost to replace the subflooring and to lay down new flooring would cost somewhere between $4,000 and $7,000, Grumbine said, with another $2,000 for new insulation.

The cost to replace Johnson’s covered wooden deck would be around $7,000, he said.

Same storm, different states — different outcomes

Immediately after the February flood, the Virginia Department of Emergency Management and FEMA teams came into the community to assess damage. Nearly two months later, the federal agency determined that Southwest Virginia qualified for public assistance as a result of the storm. That determination came weeks after Kentucky and West Virginia were greenlit to receive individual and public assistance to help them recover from the same storm that hit Richlands.

“Why that happened, I’m not sure. We talked pretty closely with folks on that side of the fence and they got theirs relatively quickly,” Holt said, of the disparity in response from the federal agency between the states.

Tazewell County, where Richlands is located, borders West Virginia, and the proximity of the town in Virginia to a state that received a speedy emergency declaration upset Richlands residents.

“That’s a frustrating piece both for them and for us, from a local government standpoint, because we want to help them but we have limited resources,” Holt said. “Financially, to try to respond to a disaster of that proportion — and we’re talking in Tazewell County, it was 220 homes impacted, 150 of those were in the town of Richlands. We took the brunt of it.”

Two of the poorest neighborhoods in the community were the hardest hit, Holt said.

“These are people who already don’t have the resources, they barely can make it, much less the resources to recover after a major disaster,” he added, and noted that the people need money in their pocket to help them relocate or rebuild or replace some of the things that they lost.

“That formula really does hurt us here in Southwest Virginia because it’s the same formula they use across the entire commonwealth. So when you try to reach a $400,000 threshold in Northern Virginia, you might have two houses that are damaged,” Mollo said, referring to a hypothetical level of property damage that may need to be reached to allow the state to qualify for individual assistance following a disaster.

“You do that here, you’re not going to hit $100,000 but it’s been 30, 40, 50 houses. People that are displaced from those houses. That formula is working against us here.”

“This has been months of frustration,” she said.

‘Come hell or high water’

Sherry Smith, now 51, and her first husband had fixed up and moved into her trailer after it was given to her by a friend about 21 years ago. Her first husband died later on in the trailer, before she and Mike Smith, now 62, met and married. They had been living together in the mobile home for about 16 years.

“I had preached, I want to move, want to move, want to move. I said, come hell or high water, but I didn’t mean actually high water,” she said, as she stood outside of her home on a sunny Saturday afternoon and smoked a cigarette. “This one tore my trailer all to pieces.”

Inside, Sherry pointed out stains left by floodwater on the couch that served as a marker for how high the water got in the trailer. The oppressive, earthy smell of mold and mildew hung in the air and made it hard to breathe under the N95 masks she and Mike wore. Sherry had just gotten out of the hospital after a bout of pneumonia, and Mike is battling lung cancer and cirrhosis of the liver, she said.

Mike pointed out stains and evidence of leaks in the ceiling from the rain and bowing in the hall wall from the floodwater. The ghostly outline of pictures and a television set were visible on the water-stained walls.

Outside, ducks waddled past, fresh out of the swollen creek that ran less than fifty yards from where the Smiths’ mobile home stands in downtown Richlands, Virginia.

A severe storm had blown through the area the night before and brought with it heavy rain and anxiety for town residents who had lived through February’s flood.