Just a few weeks ago, a group attending an event at a park in Dublin in Pulaski County began noticing the hair on their heads standing up as storm clouds gathered nearby.

Static positive electricity was building in and around them, increasing the risk that a negative charge generated amid the ice crystals at the tops of the clouds miles above could connect with that positive charge at any moment. They wisely moved into an automobile and then left.

A famously documented episode of a literal hair-raising experience preceding a lightning strike occurred at Sequoia National Park in California in 1975. Two brothers, their sister and a friend noticed their hair standing straight up and got snapshots of it. Seconds later, lightning struck the mountaintop area they had hiked to. They all survived, but a man nearby died.

When thunder roars, go indoors

This is the part of the program where I am supposed to double down on the National Weather Service slogan “When thunder roars, go indoors” and tell you to always go indoors into a well-constructed building or at least an automobile when you hear the first distant rumble of thunder.

And, yes, that is very good and potentially life-saving advice. Please heed it. Go indoors if you hear thunder.

But I also know many of you don’t vigilantly and perfectly heed that advice, and that I would be a hypocrite myself telling you I have always gone inside when it is thundering.

Lightning is an insidious danger, especially in summer in our region, when storms that produce frequent cloud-to-ground lightning strikes are most likely. It doesn’t take an especially strong thunderstorm to emit a few bolts of potentially deadly lightning. There are not “lightning warnings” placed on every billowing cumulus cloud that might soon become a thunderstorm.

Certainly, if you are outside with any hint of storm clouds building and you notice your hair standing on end for no obvious reason, it is time to move inside with no delay. Experiencing static electricity building in this manner does not mean lightning definitely will strike, but it is a strong indication that it is much more likely to occur near where you are than normal.

Too close for comfort

I’ve had some near-misses with lightning over the years.

As those of you who have followed me on social media over the years know, I often watched storms roll in over the Roanoke Valley from the roof garden at what used to be The Roanoke Times building in downtown Roanoke. I was usually pretty good about getting inside before there was lightning close. But one day, I was up there and heard a sudden loud sizzle like bacon frying, followed by a big bang, and then the immediate percussive crash of ear-ringing thunder. I’m not sure where it hit but it was close. I dashed in quickly, but I could have easily been struck.

Helping lead Virginia Tech’s “Hokie Storm Chase” for 14 years, we were as vigilant as we could be about keeping the students in the vans when there was cloud-to-ground lightning close by. But one time, pulling up to observe a developing storm in the Texas Panhandle, there was a sudden bright flash and hard boom, and smoke rising out of the prairie grass maybe 100 yards from the vehicle. Needless to say, there was a record-setting dash for everyone piling back into the vehicles.

Lightning has crossed my path in other dramatic ways.

A little more than three decades ago this week, a group of elite high school athletes floating a river in northern Arkansas were hit by lightning as they took shelter along the shore, killing one and injuring several others. Covering that for the newspaper I worked as a sportswriter for at the time was one of the most poignant and life-affecting stories I ever wrote in my early journalism career. Swinging on the front porch with a pastor who just lost his son and shooting hoops with a teenage girl, the Most Valuable Player of a state title-winning team the previous season, just days after she had been injured was deeply humbling and inspiring, something that has stuck with me to this day. (She and her team went on to win another state basketball championship two years later.)

Lightning can travel many miles outside storm

Fleetwood Mac was just plain wrong when they sang “Thunder only happens when it’s raining.”

We do not often have “dry thunderstorms” in the Eastern U.S., where lightning strikes from high-based cumulonimbus clouds out of which the rain entirely evaporates before the reaching the surface. That is a more common occurrence that can spark wildfires in Western states. But we do fairly often have dry lightning stirkes in the sense that a bolt hits outside the part of storm in which it is raining, sometimes even where the sun is shining.

The National Weather Service cites 10 miles as a common distance lightning can travel outside of a thunderstorm. In many cases that may be so far away that you don’t hear the thunder caused by the lightning bolt, or the rumble arrives almost a minute later (every 5 seconds between lightning flash and thunder is approximately a mile of distance). There have been some accounts of “a bolt out of the blue” traveling even longer distances to strike, usually involving people in exposed areas at alpine elevations. A 477-mile-long bolt was recorded by satellite over the Gulf Coast states, but it remained in the clouds.

The NCAA has established 8 miles as the radius around outdoor competition venues in which a lightning strike triggers an automatic delay of 30 minutes, the delay resetting every time there is a bolt within that radius.

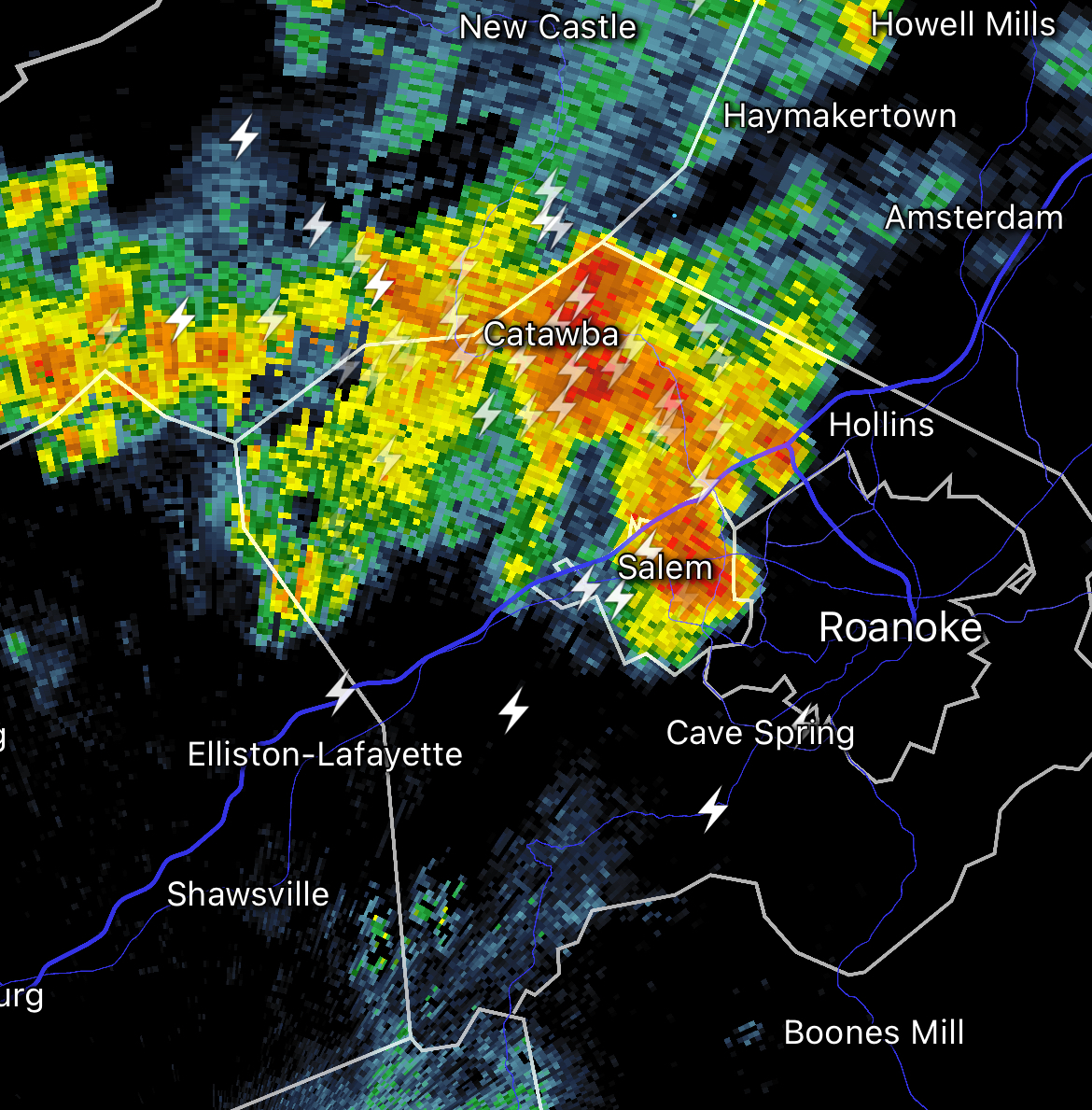

There are several weather apps that track lightning bolts and allow one to calculate how far away each strike occurs. You will notice in the photo above that I used RadarScope, but there are others available, and these can provide an alternate means of reasonable lightning safety to merely hearing thunder, which in some cases can be heard 20 or 30 miles from a parent storm. Go inside when a bolt hits, say, 8 or 10 miles from your location. This would be strongly advised for youth sports leagues to follow for their games and practices.

Bare minimum: Get out of the water if you hear thunder

Not everyone may rush inside when they hear a single clap of thunder that seems distant, but if you are in, on or near any kind of water, please heed this advice meticulously with as much haste as possible.

Just last week, 18 people were injured, 12 requiring hospitalization, when lightning struck a lake in South Carolina. It was sunny at the lake at the time the lightning struck, traveling out of a storm several miles to the south. Metal cables and buoys in the water contributed to the electricity being channeled toward the swimmers.

In a similar vein, a 29-year-old man on his honeymoon was killed just a day before at New Smyrna Beach, Florida, when lightning from a storm not yet overhead struck him standing ankle deep in the ocean.

Water is a dangerous conductor of electricity, the current traveling easily within bodies of water. Getting out of water, away from tall objects or metal, dramatically reduces your chances of being hit by lightning even without getting inside a sturdy structure. There is nothing to be gained by being in water with a storm that is at all visible or audible. (That includes the shower and bathtub in your home as well!)

Perhaps a close second to this would be getting off the golf course.

You’re in a large open area with a few isolated trees, often the tallest object for many yards around, sometimes teeing off from a hilltop. You’re carrying metal clubs in a bag and may be wearing metal-spiked shoes and there are often water hazards nearby, “hazards” having a whole new layer of meaning where lightning is concerned. You are a prime lightning target.

Professional golfing great Lee Trevino was struck by lightning at a 1975 tournament.

It is simply not worth trying to beat your handicap to stay on the course if there is a storm anywhere remotely nearby.

What if you can’t go indoors?

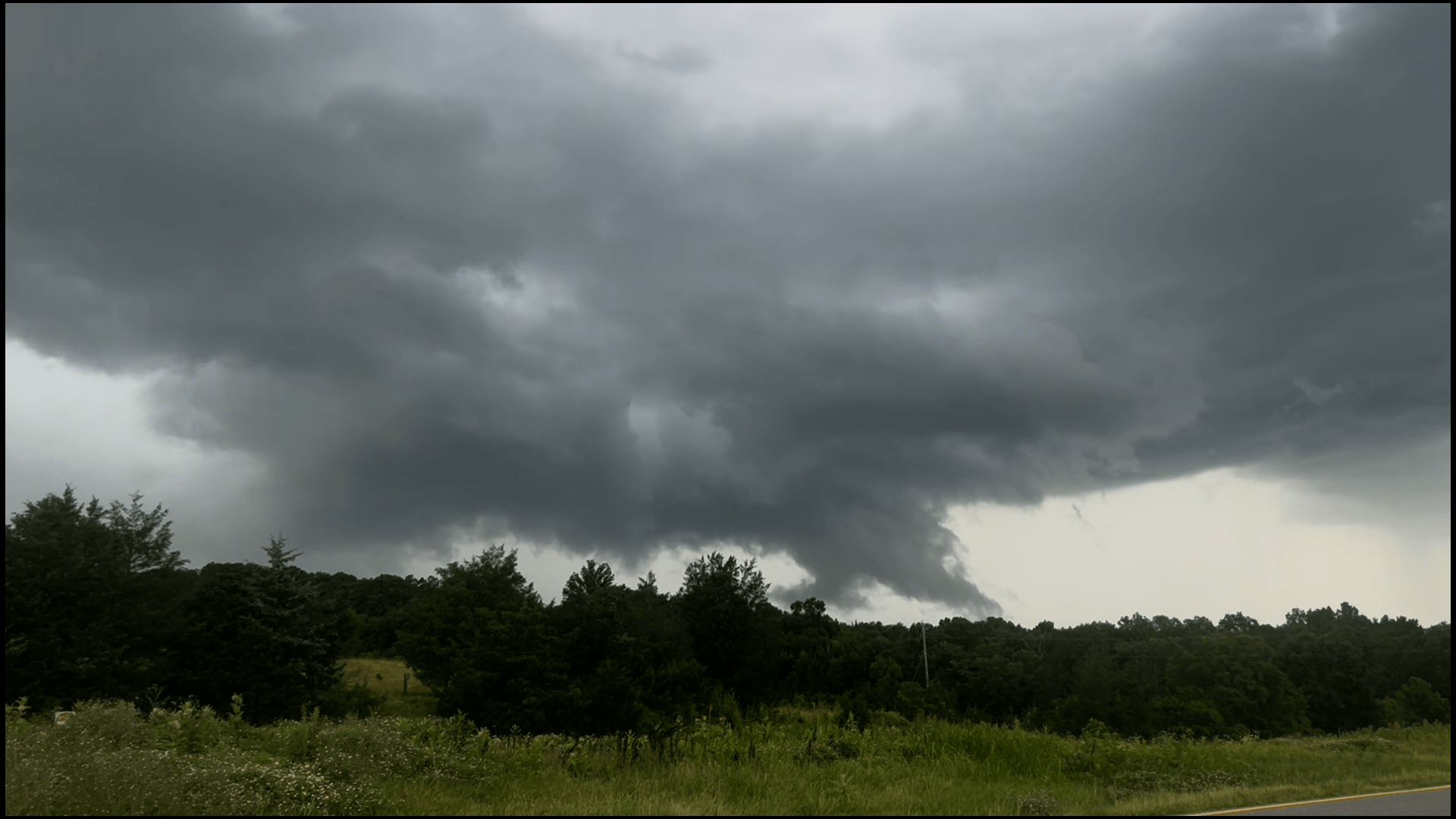

Caught in the outdoors with no indoor shelter nearby as a storm moves in, as I have been on a few occasions during longer hikes, the most important thing is to not be the tallest or highest object around and to not be very close in proximity or connected in any way, say through roots, to the highest or tallest object around.

Heading to the lowest location nearby and staying as far away as possible from tall trees and rock outcroppings is a reasonable safety step. Be aware, though, not to be in a spot that floods quickly if you are in heavy rain or a place that puts your feet in a puddle, remembering the water conduction dangers.

If the lightning seems particularly intense and close, crouching down while balancing on the balls of your feet can do the most to reduce both your height and the surface area of your body touching the ground. Never sit or lie on the ground, as current can travel through the soil, and those postures would maximize one’s surface contact.

Statistically, there is very little chance any particular tree near you will be struck if you are walking through a forest of fairly even-sized trees away from rock outcroppings and ledges. But don’t take shelter under an isolated tree in a meadow or forest opening.

Avoid standing under rock overhangs or in shallow caves during lightning. They may seem sturdy enough to block lightning, but the current can jump the gap like a spark plug and fry whatever or whoever is below.

Why an automobile is relatively safe

If you are not touching any kind of metal connected to the outside of the vehicle, being inside one is a statistically safe place to be in a thunderstorm.

It’s not because the tires are made of rubber — that rubber is often laced with steel belting, and in any event, the thickness of rubber in tires would not be enough to deter a millions-volt bolt from blasting through, no more than rubber sneakers can stop a person from getting struck.

An automobile’s metal frame creates a “Faraday cage” in which electricity flows through the path of least resistance around its occupants rather than through them.

This doesn’t mean the automobile won’t be rendered immobile as its electronics are fried by lightning. ESPN commentator Lee Corso’s rental car drove only a short distance before dying after famously being hit by lightning outside the canceled Georgia Tech-Virginia Tech football game at Lane Stadium in August 2000.

Heat lightning is not a thing — and neither is heat lightening

By the way, there is no such thing as “heat lightning,” or lightning that is entirely caused by high temperatures.

What does often happen in the summertime is that storms pop up in the heat and humidity — we’ve seen plenty of those in previous days. Sometimes these storms are beyond the horizon of our view. When it gets to be evening, we may see the flash of that lightning spreading beyond the horizon but be too far away to see the bolt, hear the thunder, or sometimes even see the thunderstorm clouds. That is “heat lightning.”

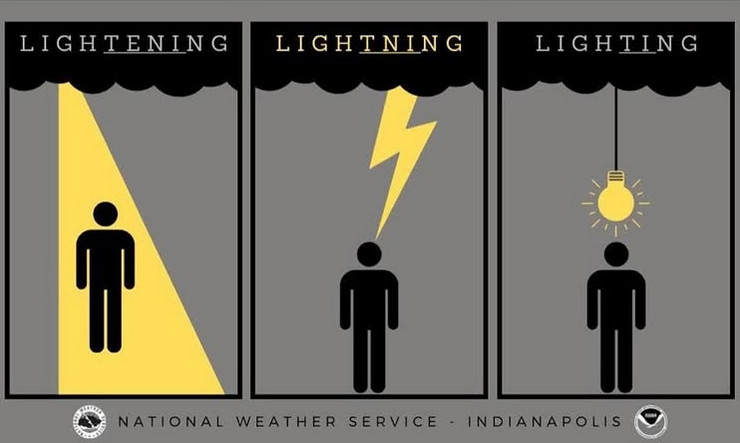

And while we’re at it, always remember that “lightning” doesn’t have an “e” in it. It’s not “lightening.”

Journalist Kevin Myatt has been writing about weather for 20 years. His weekly column, appearing on Wednesdays, is sponsored by Oakey’s, a family-run, locally-owned funeral home with locations throughout the Roanoke Valley. Sign up for his weekly newsletter: