This year marks a full century since Roanoke ceased to be “the Black Hollywood.”

If you never knew that Roanoke once held that title, then we have a lot of catching up to do before we get to why Roanoke’s status is back in the news, at least indirectly.

For four years, from 1922 to 1925, Roanoke was the home of Oscar Micheaux, who is regarded as America’s first Black filmmaker — even though he wasn’t, but that’s just one of many things about his life that weren’t quite so. He was, however, undoubtedly, the first major Black filmmaker — one who operated completely outside the Hollywood studio system of the time (and sometimes outside the law). The films he made were not necessarily great art, but the fact that he was able to make them at all is a testament to his hustle and his fortitude at a time when both racism and censorship (not to mention a lack of funds) constrained his work.

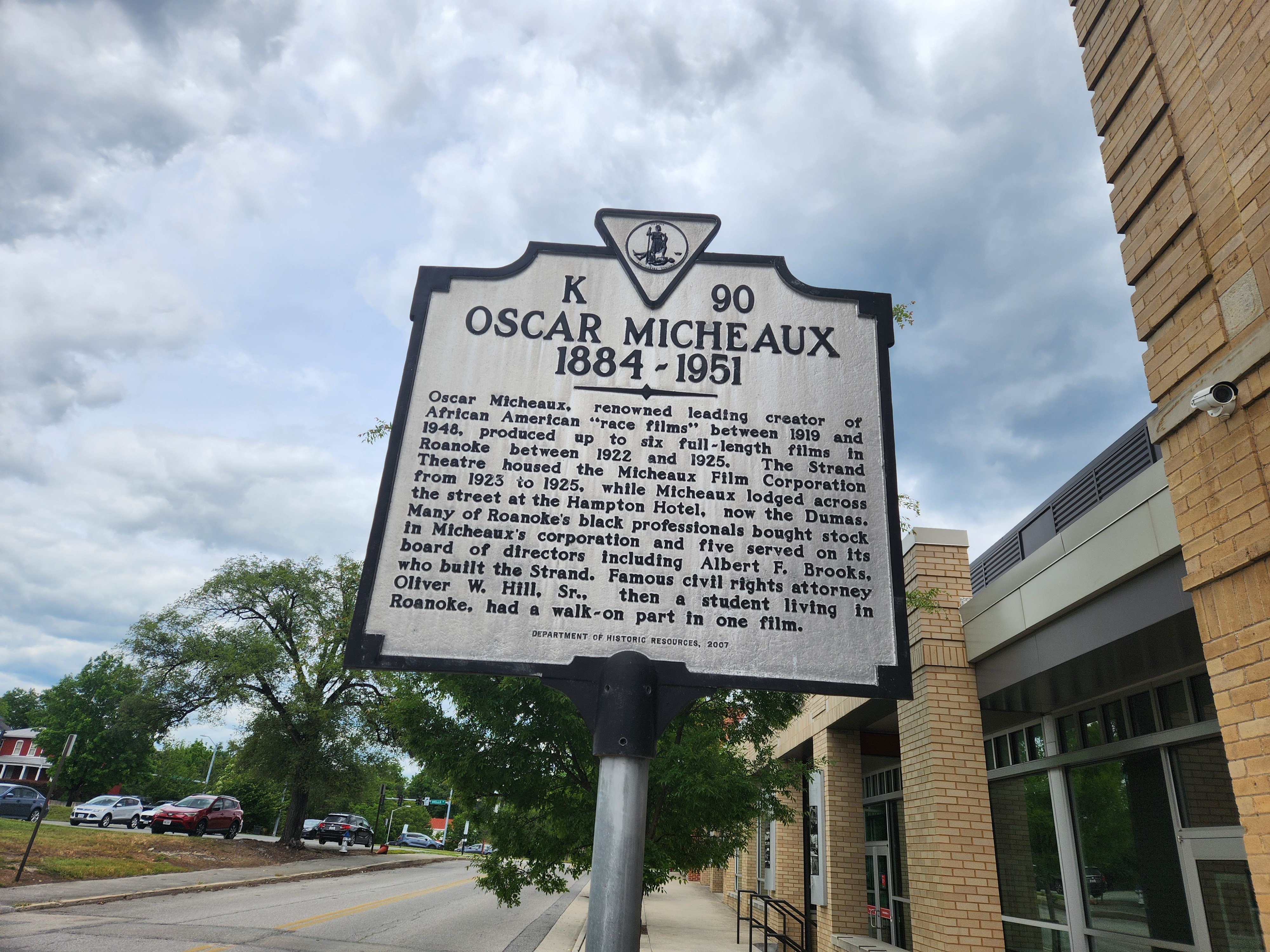

Every independent filmmaker today, Black or otherwise, owes some debt to Micheaux, whose name is now largely lost except to film historians. The “largely” adjective exempts Roanoke, which has a historical marker to Micheaux in the Gainsboro neighborhood where he operated. The event that has brought Micheaux back into the news is that a New York-based film distribution company has recently released a five-disc set that it bills as “Oscar Micheaux: The Complete Collection.”

Alas, “complete” is not what it may seem. Micheaux may have made as many as 44 films; only 18 survive, and some of those are incomplete. This collection contains the 15 complete ones.

Even more sadly for us, none of those are the ones he filmed in Roanoke.

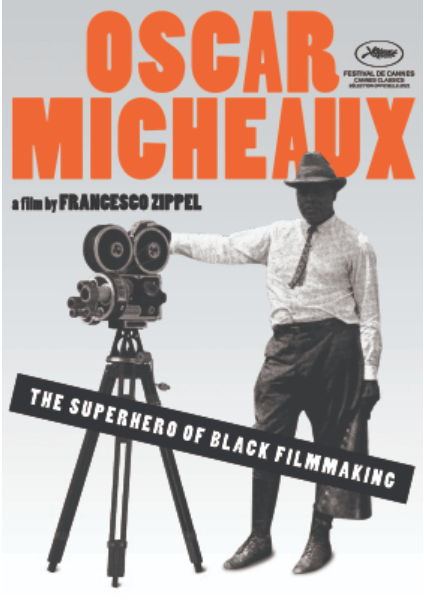

Nonetheless, Micheaux stands as a forgotten giant in American culture. Besides releasing this “complete collection,” the Kino Lorber film company has also released a DVD version of the 2021 documentary “Oscar Micheaux: The Superhero of Black Filmmaking,” which includes appearances by Morgan Freeman and the late John Singleton.

All this was enough to merit attention recently in The Wall Street Journal, which said Micheaux “displayed remarkable artistic ambition and an abiding interest in exploring the social issues that Hollywood preferred to sidestep.”

For four eventful years, Micheaux conducted that exploration in Roanoke.

* * *

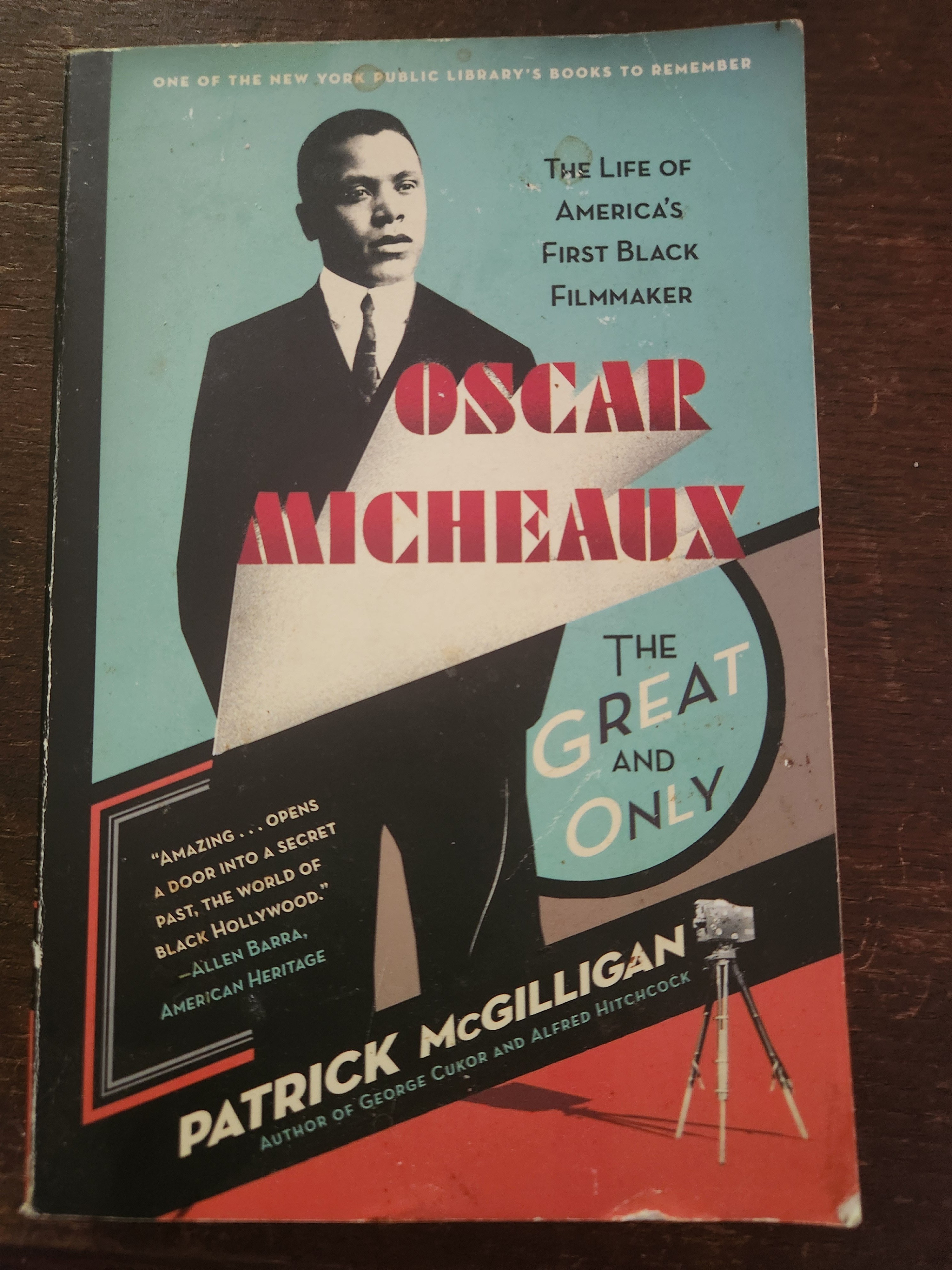

If you want to know more about Micheaux, I recommend the definitive biography: “Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only” by Patrick McGilligan. His life was far more complicated than I can capture in a single column.

Micheaux was born in 1884 in downstate Illinois. He had no interest in farming, his father’s occupation. Young Oscar was an entrepreneur at heart, although he didn’t realize that yet. At 17, he moved to Chicago. For a time, he ran a shoeshine operation, his first business. At 19, he signed on as a Pullman porter, then considered a prestigious job for a Black man because it offered steady employment, travel and decent wages for the time. McGilligan also explains that these jobs were often rife with shady operations where porters underreported the cash they collected from certain ticket sales and pocketed the rest. Micheaux nervously took part in those embezzlements, the biography says, although his nervousness appeared to stem more from fear of being caught than misgivings about the morality of it all. After two years, he was fired, not for these “knock-downs,” as they were called, but for pinching $5 from a passenger’s purse.

Nonetheless, those two years as a Pullman porter fattened Micheaux’s bank account, introduced him to wealthy white businessmen who would later be helpful to him and gave him lots of time to read. “Micheaux absorbed everything he got his hands on: newspapers, muck-racking articles in magazines, government land reports, history books and novels,” McGilligan writes. He read Shakespeare, he read Westerns. “What I liked best,” Micheaux later wrote, “was a good story with a moral.”

Although he grew up hating farming, Micheaux decided to try his hand at it anyway, in South Dakota. He entered into an unhappy marriage to a preacher’s daughter that embittered him toward all ministers. He took to writing articles about the supposed glories of homesteading in South Dakota for The Chicago Defender, an influential Black newspaper of the day. That led to Micheaux writing a novel based on his life, “The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer,” which he then set out to sell as both an author and publisher. A second novel followed, then a third, all loosely based on his life.

Another medium was starting to mesmerize the public, though: movies. Micheaux decided to turn his third novel into a movie. He was not the first Black filmmaker. William Foster of Chicago founded the Foster Photoplay Company in 1910. His film, “The Railroad Porter,” is said to be the first film with an all-Black cast. His business closed three years later, though. Micheaux came along with his first film in 1919 — and he stuck around.

Micheaux was a good promoter and, thanks to his Pullman days, had connections across the country. What he didn’t often have, though, was money, or a coherent approach to storytelling. His films were “often interrupted with digressions, social observations and data, flashbacks (even flashbacks within flashbacks),” McGilligan writes, which often rendered his work “tedious and confusing.” In those days, that didn’t matter much. No one was doing what Micheaux was doing: producing films for a Black audience.

Micheaux often made topical films that incorporated whatever the news of the day might be (especially if it was scandalous). He portrayed lynching and white-on-Black sexual violence “with a luridness and savagery rare in the American cinema,” McGilligan writes. Those themes also ran afoul of many censorship boards that dictated what movies could be shown. “Everywhere in America, but especially in the Deep South,” McGilligan writes, Micheaux’s films “were scrutinized for every conceivable violation, any inference that defied that prevailing social order.” One reason so few of Micheaux’s films survive is that he couldn’t afford to make many copies of each one, and some of those copies were physically cut apart and spliced back together to eliminate troublesome scenes. The results were often choppy stylistically. That also meant there might be different versions of the same film in circulation (much like how there are multiple versions of Shakespeare’s plays for the same reason).

Micheaux migrated across the country, hoping to stay ahead of creditors and find more agreeable censorship boards. From South Dakota, he went to Chicago, then to New York and, in 1922, to Roanoke. Micheaux had already set up a business office in Roanoke to service the South. He decided to move there full time because it was cheaper than New York and he could shoot a lot of scenes outdoors. He also liked Roanoke, McGilligan writes, because it had “enterprising Black businessman who ran a few theaters.” Micheaux’s story gives us some insight into Roanoke’s complicated history.

The Association of Commerce — presumably a forerunner of the chamber of commerce — welcomed Micheaux’s arrival in the spirit of what today we’d call economic development. “In time,” McGilligan writes, “the civic organization would schedule private screenings of the Roanoke films for local white businessmen at the city’s white theaters.” When Micheaux filmed “The Virgin of the Seminole,” “a local farm was turned into a cattle ranch and the parks and streets of the city were momentarily filled with galloping dark-skinned cowboys.” The movie was a big hit nationally, which helped Micheaux’s finances — at least temporarily.

It’s unclear how many movies Micheaux shot in Roanoke. Some films were announced but never produced. Some might have been filmed but never released because Micheaux couldn’t pay a lab to develop the film. Other films might have been seized by creditors. Sometimes, partially produced films might have been spliced together to create an entirely new one. McGilligan details how Micheaux had lots of trouble with all those things and was often content with less-than-perfect work.

It’s possible Micheaux made as many as eight movies during his time in Roanoke. The only one that survives, “Body and Soul,” was shot in New York, though. It’s notable for another reason: It marked the film debut of Paul Robeson, who went on to stardom.

Micheaux himself was not so lucky.

He was often in trouble with the law. Micheaux’s 1924 film “Birthright,” filmed in Roanoke, was considered a groundbreaking work about racism in the South, but that made it suspect in the eyes of Virginia authorities. McGilligan says the film was shown in Lynchburg, Roanoke and Norfolk without approval of the state censorship board. When “outraged white citizens” alerted the board, it sent notices to mayors and police chiefs across the state, warning them that “it is an audacious violation of the law to display this picture and theater managers exhibiting it are liable to prosecution.” The theaters in question claimed they didn’t know the film hadn’t been approved yet; it appears that Micheaux had “fraudulently” attached his authorization from a different film.

The censorship board wanted to prosecute Micheaux, but Attorney General John Saunders advised it would be sufficient to ban his future productions until he made “Birthright” available to the censors. Micheaux wrote the board, pleading that someone else had mistakenly shown the film. McGilligan calls that letter “a masterpiece of cunning and dissembling.”

The board wasn’t appeased. Micheaux’s next Roanoke-made film was “A Son of Satan,” a “quasi-comedy about a haunted house taken over by a Ku Klux Klan.” Based on the reviews, McGilligan calls it “one of the most intriguing of Micheaux’s lost works.” Virginia authorities weren’t moved by what the reviewers said, though. When “A Son of Satan” was set to open in Norfolk, “the state censors sent a telegram to stop the film, followed by a ‘detail of policemen’ who seized the print and turned away ‘scores of theatergoers’ on the opening night of a three-day engagement.” That’s another reason why some Micheaux films were lost: Prints were seized and never returned.

Micheaux was also constantly in debt; it was money troubles that eventually forced him to move back to New York to be closer to a bigger market. When he began making movies, he was a darling of the Black press. As time went on, critics multiplied. One recurring complaint by Black critics: Micheaux’s heroes and heroines were often light-skinned, his villains more dark-skinned. Both technology and economics began to work against him. Hollywood could produce spectacles that he simply couldn’t afford. Movie houses catering to white audiences adopted air conditioning; those aimed at Black audiences couldn’t afford that.

Over time, Micheaux’s movies became more infrequent, and less celebrated. “The Betrayal,” which came out in 1948, was a bust. Micheaux never made another. He was out of money, and his health was failing. He died three years later and was buried in an unmarked grave in Kansas.

* * *

Decades later, Micheaux was “rediscovered.” Scholars began to study his work. Fans raised money to put up a headstone. The historical marker in Roanoke went up. And now documentaries are made about him. Film scholars to this date hope that some of Micheaux’s lost work may someday be found. However, it’s been almost three decades since the last such discovery, and celluloid of that era deteriorates. That newly released “complete” collection may be as complete as it ever gets.