Improving attendance at Norton public schools sometimes looks like tracking down one chronically absent student at a time. Sometimes, that entails going to find them at their part-time jobs.

Sarah Davis, the attendance specialist at the small Southwest Virginia school division, recalled one student who was skipping afternoon classes so she could pick up extra shifts at a local fast-food chain.

“That woman’s here!” someone shouted the last time Davis walked into the restaurant looking for the student. Davis knew she was hiding somewhere beyond the counter.

The student was 18, so no one could force her to attend school. Davis just wanted to have a conversation. She just wanted to find out why the student was skipping school and figure out how to get her back in class.

Davis called out that she wasn’t going anywhere. She was going to order something, and “I’m going to sit here,” she said. “So come on out.”

Eventually, the student came out and sat down with Davis to talk. She agreed to change her work schedule so she could go to class but still earn money after school. It worked.

Davis got to see that student graduate.

She only works three days a week for Norton City Schools. Her position is a new one for the division, funded by a statewide effort to improve school attendance that began in 2023. It’s a job that entails lots of outreach to families, keeping a close eye on attendance records for the city’s 850 students across an elementary/middle school and a high school, and sometimes picking up students who missed the bus.

Educators across Virginia hope that boosting attendance will accelerate the rebound of learning benchmarks that have lagged since the pandemic.

Davis’s efforts, combined with those of school administrators and a nonprofit partner organization, have made significant progress to improve attendance in Norton.

For the 2022-2023 school year, more than one-third of the 325 students at J.I. Burton High School were chronically absent, meaning they missed more than 18 days of school for any reason.

For the 2023-2024 school year, chronic absenteeism dropped from 37% to just 2%.

Across both schools in the division, chronic absenteeism dropped from 26% to 8%. Norton had the greatest reduction in chronic absenteeism by a school division anywhere in the state. Virginia’s overall chronic absenteeism rate stands at about 16%.

The division’s progress is an example of the work it often takes to get students into the classroom each day.

Relationships at the heart of effort to increase attendance

Much of Norton’s progress in boosting attendance can be credited to communication.

Before the All-In VA plan, which put $418 million in state funding toward learning loss recovery, literacy and attendance, Norton’s two schools had different attendance policies. That created confusion when a student moved from Norton Elementary and Middle School, which houses pre-kindergarten through seventh grades, to Burton High, which houses grades eight through 12.

The school board reviewed the attendance policies across the two schools and aligned them so that expectations were the same for students in all grade levels.

Norton also created an online form for parents or guardians to fill out when a child is absent, rather than needing to call the office. The form makes tracking absences easier for school staff, and though Davis said using it is encouraged, the schools still accept phone calls, along with doctor and parent notes.

Having Davis focused on monitoring attendance issues has taken some pressure off teachers, who were trying to keep contact with parents about absences along with their many other duties, said Superintendent Gina Wohlford.

Beneath the communication efforts are deep relationships — ones that were there before Norton started its attendance initiatives, but have strengthened further as the school system focuses on addressing the root causes of absenteeism, administrators said.

Some of those relationships go back generations. It can be challenging to grow up in a place where everyone knows you, said Burton High School principal Brad Hart, who has worked as a division administrator for 19 years. Norton only has about 3,500 residents and holds the title of the smallest independent city in Virginia.

Instead, Hart says he’s lucky to know each and every one of his students. “I know their families, where they live, what their economic status is, what their needs are.”

Hart said that as principal, it’s been helpful to have an attendance specialist who can keep close track of when students are starting to rack up absences. From there, administrators can determine next steps, ranging from calling a parent to conducting a home visit to find out what assistance a family might need to make sure their child gets to school. They can also recommend that a student stay after school or attend Saturday school to make up lost time.

Hart said if the school fosters a relationship with a family, they know “it’s not just about the academics,” and that the school cares about the well-being of the child and their whole family.

When families understand that, they’re more likely to send their kids to school, Wohlford said.

Nonprofit coordinators provide extra support for students in need

Sometimes the barrier between a child and regular attendance comes down to basic needs.

Nearly 38% of children under 18 in Norton live below the poverty line, compared to about 13% of children statewide, according to Census Bureau data. The median household income is under $40,000 a year. Davis said the city has a lot of grandparents raising grandkids because of addiction in the area.

“I’m usually at Walmart every day for something,” said Ashleigh Collins, to pick up clothing or other supplies a student needs. She works as Norton’s lead student support coordinator for Communities in Schools of Appalachian Highlands.

Affiliates of the national nonprofit Communities in Schools provide support to students to help them succeed academically. CISAH works with more than 20 school divisions in Southwest Virginia and has partnered with Norton schools since the 2021-2022 school year. Four student support coordinators work in the two schools.

Any student can receive personal support — there’s no academic or economic threshold — and coordinators also plan schoolwide events such as holiday parties.

“When we say, ‘Anything a kid needs to stay in school,’ it’s really anything,” Collins said. Once, a student she worked with had a terrible toothache. Collins helped the student get a dentist appointment quickly, got the insurance information from her parent, drove her to the appointment and then took her home. Addressing the toothache reduced the learning time the student would miss because she was in pain. But greater than that, it simply solved the student’s pain at the source.

Collins runs regular contests and friendly competitions to encourage students to attend school regularly. One such incentive was a raffle: Each time a student attended school for a full week, their name got entered into a drawing for a pair of Nike Air Jordans. Collins said the winner actually chose to get a pair of welding boots instead of the sneakers because he was about to start welding school.

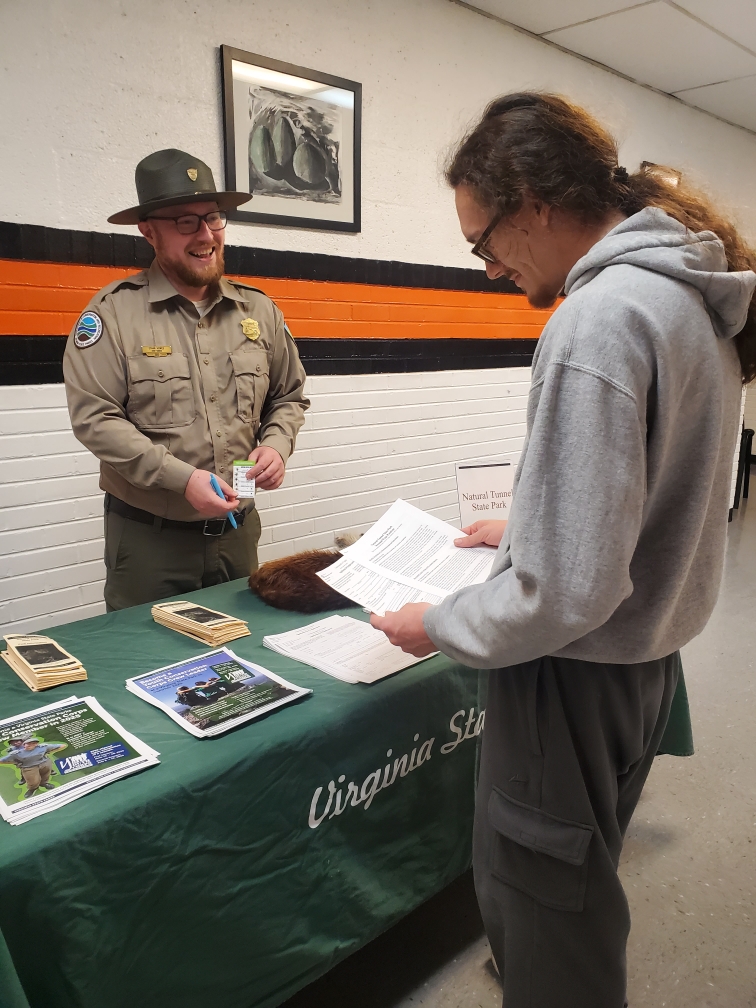

Sometimes a celebration can be as simple as a picnic in the park with a group of students, she said. She also plans field trips for career and college prep opportunities, and she brings people with different careers to the school to meet students: everything from the owner of a popular food truck to state park rangers.

Collins said she tries to tell students that attending school is their chance to change their lives. This year, she set up an all-senior signing day. It gave every graduating student a chance to be recognized for their next steps in life, whether they were going on to college or into the workforce.

Norton waits to see if huge attendance gains hold

Some of the work to boost attendance comes down to shifting families’ attitudes toward education, Hart said. “It’s sort of part of growing up around this area. It was a very big coal mining area back in the day,” he said. “A lot of people forced their kids into the coal mines a long time ago, and now we’re trying to get those families to buy into how education can help their kids.”

A 2025 survey of parents of public-school students in Virginia found that almost all parents believed their children’s attendance was “normal,” when in fact one-third of their children actually fell into the chronically absent category. The survey was conducted by EveryDay Labs, an attendance management platform used by several school divisions in Virginia.

Post-COVID absenteeism wasn’t as much of an issue in Norton as it was in some other places, Hart said, because Norton was the first division to go back to school four days a week starting in August 2020.

Chronic absenteeism doubled statewide during the pandemic, topping at 20% in 2021-2022, before starting to creep back down to 16% by the 2023-2024 school year.

“School divisions have shared with us that their most successful schools have strong teams leading this work as attendance requires an all-hands-on-deck approach,” the Virginia Department of Education Office of Behavioral Health and Student Safety said in a statement in late June.

“A few of the most effective approaches include increasing opportunities for family engagement, strengthening community partnerships, supporting students in recovering missed instructional time, connecting students to mentors, and hiring additional school-based mental health professionals,” the statement said. The state office doesn’t have data on what’s been most effective in small rural school divisions versus larger or more urban ones, it said, but it noted that each school division is encouraged to tailor its attendance initiatives to its community’s needs.

Norton’s efforts to make up missed instructional time mean administrators don’t know what their chronic absenteeism will ultimately be for the 2024-2025 school year.

“We have really been pushing our after-school and Saturday programs,” Wohlford said. Those hours can make up for missed classroom time, and the impact is calculated by the state education department. The department typically releases that info for the prior academic year in September.

Wohlford thinks attendance overall may slip a little compared to last year’s strides. “But we still think overall, we’ve made tremendous improvement as a division.”

For the coming school year, the division is working with local health care partners, hoping to expand mental health access for students, including access to practitioners who can prescribe medication where needed.

The division is also looking at ways to further alleviate transportation barriers to attendance.

Davis would like to figure out how to get funding for a van and a driver who can be sent out if a student needs a late ride to school.

Until then, she knows that if a student needs a ride to school, someone will grab their keys and go get them.