Annie Mosby sat at her desk inside the one-room schoolhouse where she was once a student before Pittsylvania County schools were integrated.

Back when she was a student in the 1950s, a large potbelly stove used to warm the schoolhouse in the winters. But on a sunny Monday afternoon in June, Mosby didn’t miss the stove’s absence.

At 79 years old, she still comes back to her hometown once a year for several weeks over the summer, flying from California where she lives now, to catch up with family and spend time in the schoolhouse that she and her husband fixed up.

A book with a bright yellow cover sits on the desk next to her laptop. Mosby wrote the book to preserve the story of the schoolhouse and the community, Callahan Hill, that surrounds it.

“It’s a collection of this history,” Mosby said. “I never wrote it for the public. It’s a collection of our history for our family and community.”

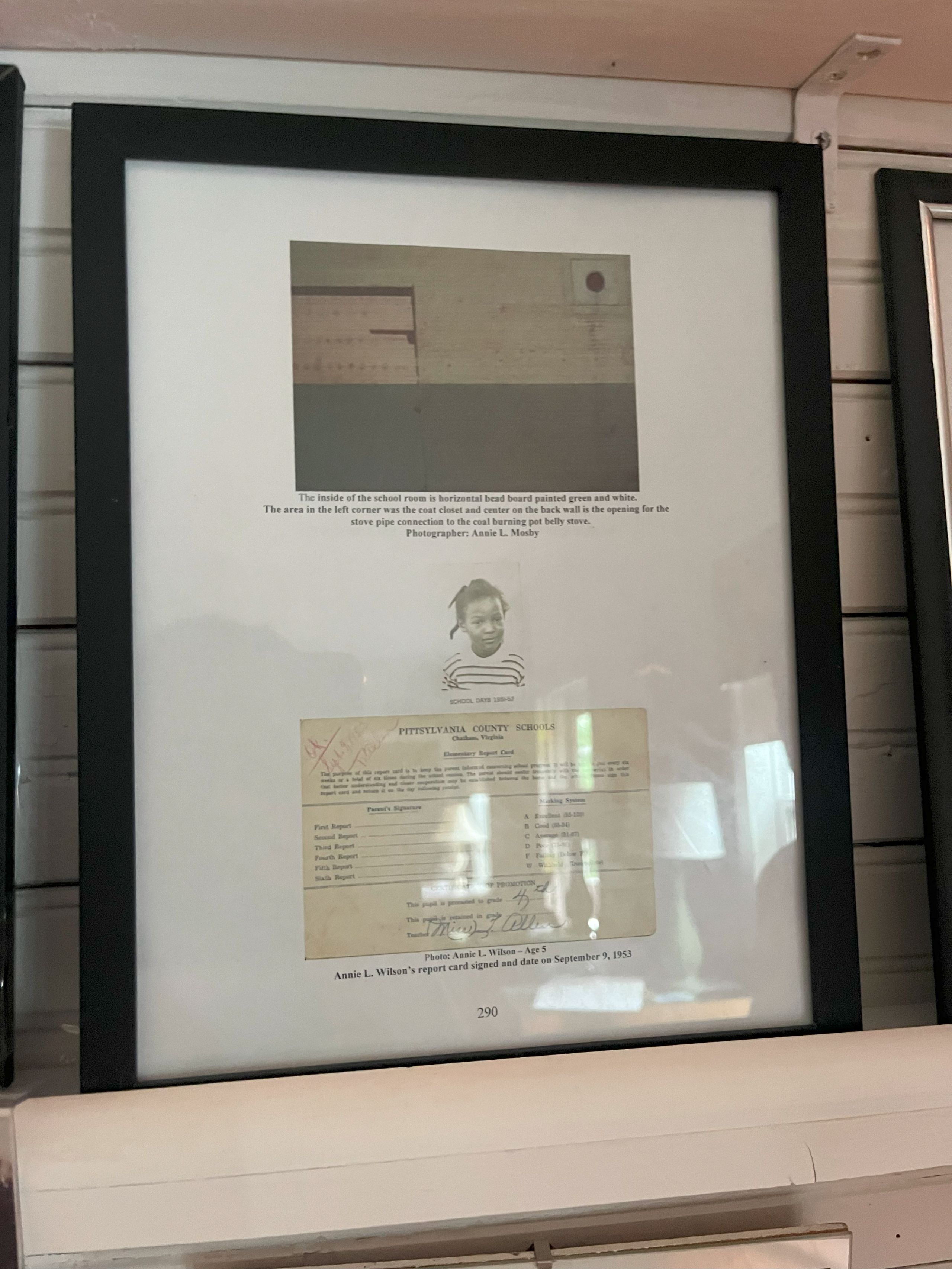

All around her are mementos from the schoolhouse’s heyday: framed class photos, grade-school books, even an old desk.

On the wall above Mosby hangs her first-grade class picture and report card. Almost every inch of the walls are covered with keepsakes like this.

They’re joined by items commemorating the country’s Black history, like the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle announcing Barack Obama’s election to the presidency, its headline proclaiming “The World Has Changed.”

About 15 years ago the schoolhouse sat empty and abandoned, back in the woods of a farm where even its former students had forgotten about it.

“Hardly anyone knew it was out there,” Mosby said. “Most schools like this in the county were torn down or sold, so we didn’t know it was there.”

Mosby grew up without hearing stories about her family history. Most of the community was descended from sharecroppers or enslaved people, and folks weren’t keen on recounting those times, she said.

She started learning about Black history in college, and became obsessed finding out more about her own family and community history.

When she rediscovered the old schoolhouse, formerly called the Harvey Colored School, she felt she had to restore it.

“My husband bought it as a birthday present for me in 2003, because that’s what I wanted,” she said.

Mosby and her husband, St. Elmo, began moving the school from its original location off U.S. 58 near the Danville-Pittsylvania County line, and onto her family land in 2011.

It was a long process — especially with Mosby only in Pittsylvania for a few weeks out of the year — but by 2018 the schoolhouse had been relocated and restored.

Now, it’s a sort of museum and gathering place for Mosby’s family and the community.

“It’s our family history,” she said. “This is the homeplace for us.”

Rediscovering history

In college, Mosby’s art professor asked the question: “Where in Africa are your ancestors from?” She was shocked to realize that she didn’t know.

Mosby never thought about her ancestors before she went to Norfolk State Community College, an all-Black school, in 1964.

“No one in my family had ever told me I had African ancestors,” she said. “I didn’t know, because no one ever talked about it. That’s when I got interested, and I came home and asked my mother about it. She didn’t know either.

“I said, ‘Mother, y’all saved no history for us,’ and she said, ‘Well, the schoolhouse is out there in the woods.’”

Her mother took her to the former Harvey school, and that was the first time Mosby had been back since she was a student there, attending first through sixth grade. She had forgotten about it entirely — almost everyone had.

The Harvey schoolhouse was built in 1880, predating even the Rosenwald schools of the 20th century. The Rosenwald Schools were a network of more than 5,000 schools to educate Black children in the rural South.

Before that, most schools for Black children originated in churches, said Karice Luck-Brimmer, a Black historian and genealogist in Danville.

“The Harvey Colored School, it started from the Mount Lebanon Baptist Church,” she said. “It pretty much educated people all up and down 58 West. … A lot of students were the descendants of enslaved people at the Berry Hill plantation. The Hairstons, Perkins, Wilsons — they all attended this school.”

Mosby is a Wilson, one of the families that was enslaved at Berry Hill. Wilson is her maiden name, which she changed to Mosby after marrying St. Elmo 59 years ago.

After revisiting the schoolhouse with her mother, Mosby said she wanted to learn everything she could about her family and community history by talking to her elders. She learned that her great-grandparents were born into slavery and owned a farm after emancipation, which was more lucrative than sharecropping.

Gathering these oral histories, she heard tales of the tight-knit community that she had experienced as a child.

“Callahan Hill was a village filled with relatives, friends and neighbors who knew it was their responsibility to care for loved ones, parents, and grandparents,” she wrote in her book. “Every adult was watchful and a guardian of the neighborhood children. I felt secure from the harshness of the world outside of Callahan Hill.”

She was shocked by the stories she heard, and how they differed from what she learned in school. Mosby decided to take it upon herself to preserve the history of the community — and the schoolhouse.

“I would have rather heard the African American version of slavery than the white-washed version written in the history books,” she wrote in her book, “The African American Village of Callahan Hill.”

The book includes many of these stories, and details what life was like in Callahan Hill — fond memories like listening to blues on the jukebox in her Uncle Oliver’s restaurant, the Chicken Shack, alongside the hardships of living in the South during segregation.

There weren’t many copies of the book printed, and it’s not meant to be distributed to the public, Mosby said.

Instead, it’s personal. It’s “the path I took to learn about my ancestors,” she wrote. “The book is a reference book for our children. I hope it will inspire individuals to ask questions, research and learn more and share it with their families.”

Plank by plank

By 2003, Mosby was seriously interested in buying and restoring the schoolhouse. It had closed in 1964, when county schools were integrated.

The land it sat on was part of a larger tobacco farm, which was then owned by former Danville City Attorney Ewell Barr and his wife, Lamar.

The Barrs had inherited the land but had no connection to the schoolhouse, which they were using for tobacco storage and were willing to sell, Mosby said.

Mosby and her husband bought the schoolhouse — just the building, no land — for $1,500 and began the process of relocating it, one piece at a time.

It was like taking apart a puzzle and putting it back together, Mosby said.

They worked with a local architect, William Jerome Johnson.

“I’d hire him every summer and I’d come home for 30 days,” Mosby said. “We took the school apart plank by plank, and labeled every piece of wood.”

They put the boards on a trailer and pulled them to Callahan Hill, to the yard behind the house where Mosby’s brother and sister live. That’s where they started to put it back together.

“Everything in this schoolhouse is original except for the windows and the doors,” Mosby said. “The roof is original, too.”

They added a few extra rafters, Mosby said, because modern building codes require less distance between rafters than the 1880 original build.

With that exception, and the absence of the potbelly stove, the structure looks about the same as it did when Mosby attended school there.

This exact replication was possible because the schoolhouse was in good condition, despite its age. It had been built on cinderblocks, which acted as stilts and allowed air to get underneath the building, Mosby said.

“They never underpinned the house, so over all those years, the air circulated underneath it and it didn’t rot,” she said.

The Harvey School is also unique in that it wasn’t demolished, like so many other segregated schools of the time, Luck-Brimmer said.

“Almost all of them have been torn down,” she said. “There are some Rosenwald schools that have been repurposed for someone to live there, but a lot of those early schools that predate the Rosenwalds, they don’t exist.”

The Harvey School is likely the oldest school in Southside Virginia that is still standing, she said.

Luck-Brimmer is working with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources to collect photos, videos and other documentation of the schoolhouse so that its story can be told. She’d love to eventually see a state highway marker recognizing the Harvey School, she said.

Still, the motivation to restore the schoolhouse was mostly personal for Mosby. She wanted it to belong to the community it served.

From start to finish, the project cost between $40,000 and $50,000, Mosby said. All of the money came out of her own pocket, and she even took a carpentry class during the process.

“I worked a part-time job in California and saved my money. … I saved every penny,” she said. “And every year I came home and I had set aside so much money, so much planning, so much time to work on this.”

They began the process in 2011, and by 2018, the schoolhouse had been reconstructed and Mosby had decorated the inside with Black history memorabilia, both local and national.

The decor pays tribute to teachers at the Harvey School, like Thelma Allen and Lelia Richardson.

When Mosby attended the Harvey School, Allen was the only teacher in the one-room schoolhouse, where she sometimes taught as many as 72 children from first to seventh grade, Mosby recalled.

“You can’t imagine a teacher having 72 students, so what she would do was take a kid who was good at math and put him with a kid who needed help with math,” Mosby said. “She would use the kids to help each other.”

Callahan Hill families knew each other and kept an eye on one another’s children, Mosby said.

“We were all in the same neighborhood, our parents knew each other, and your teacher had an investment in you because she knew your parents,” Mosby remembered. “And we respected Ms. Allen because she had the permission of our mothers to discipline us. You didn’t act up too much in school because even without phones, sometimes the message got home before you did.”

‘The homeplace’

Mosby doesn’t want the schoolhouse to be open to the general public. It belonged to the Callahan Hill community when it was operational, and it should stay that way, she said.

Her family uses it as a home base for gatherings. She also gets visits from former students who want to see the schoolhouse again.

Mosby has tried to track down all of the Harvey School’s former pupils. She advertised the formation of a Harvey School Historical Society in newspapers and at churches in 2004, and found a lot of former students that way.

Johnson, the architect who helped her relocate the school, died in 2017, a year before the school was entirely rebuilt. Although he wasn’t formally trained in this trade, Johnson had an eye for building, Mosby said.

“Without him, that school wouldn’t be here,” Mosby said. “So many African Americans back in the day didn’t have the opportunity, even though they may have had the skill. … You know how people just naturally play piano by ear? He had housebuilding just in his head like that.”

Mosby uses the schoolhouse as an office when she comes back to Virginia. Luck-Brimmer likes to visit the schoolhouse, just to soak in its history and community.

It means a lot to the Callahan Hill area to have the schoolhouse restored, said Luck-Brimmer, adding that she’d love to see a historical marker there someday.

“As far as early education, to have a schoolhouse right there within the community, it meant a lot.” she said. “Schools like these were few and far between.”