The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

A thin layer of clouds stretches across the late-winter sky while children take advantage of an early March thaw to play in their yards and ride bicycles along Ivy Farm Road. Down on the corner, a few neighbors converse in a driveway dressed in sweatshirts as the temperature hovers in the low 60s.

Just five miles away, the popular Barracks Road Shopping Center, at the intersection of Barracks Road and Emmet Street, hosts more than 80 shops and restaurants and is described by the Charlottesville Albemarle Convention & Visitors Bureau as “the cream of the crop” of Charlottesville retail, bringing together “the best of local and national brands in one, convenient spot just minutes from the University of Virginia, Monticello, Michie Tavern, and downtown Charlottesville.”

It’s a far different vibe than what Schüler Von Selden experienced when he arrived in Albemarle County in mid-January 1779, following a 70-day, 650-mile march from Boston.

Von Selden, a German officer who fought with the British, made his way to what is now the Ivy Farm subdivision a few miles northwest of Charlottesville as a prisoner of war, captured at the seminal 1777 Battle of Saratoga, New York. Nearly 4,000 other prisoners of that battle accompanied Von Selden, caught up in a game of political chess between the British government and the Continental Congress.

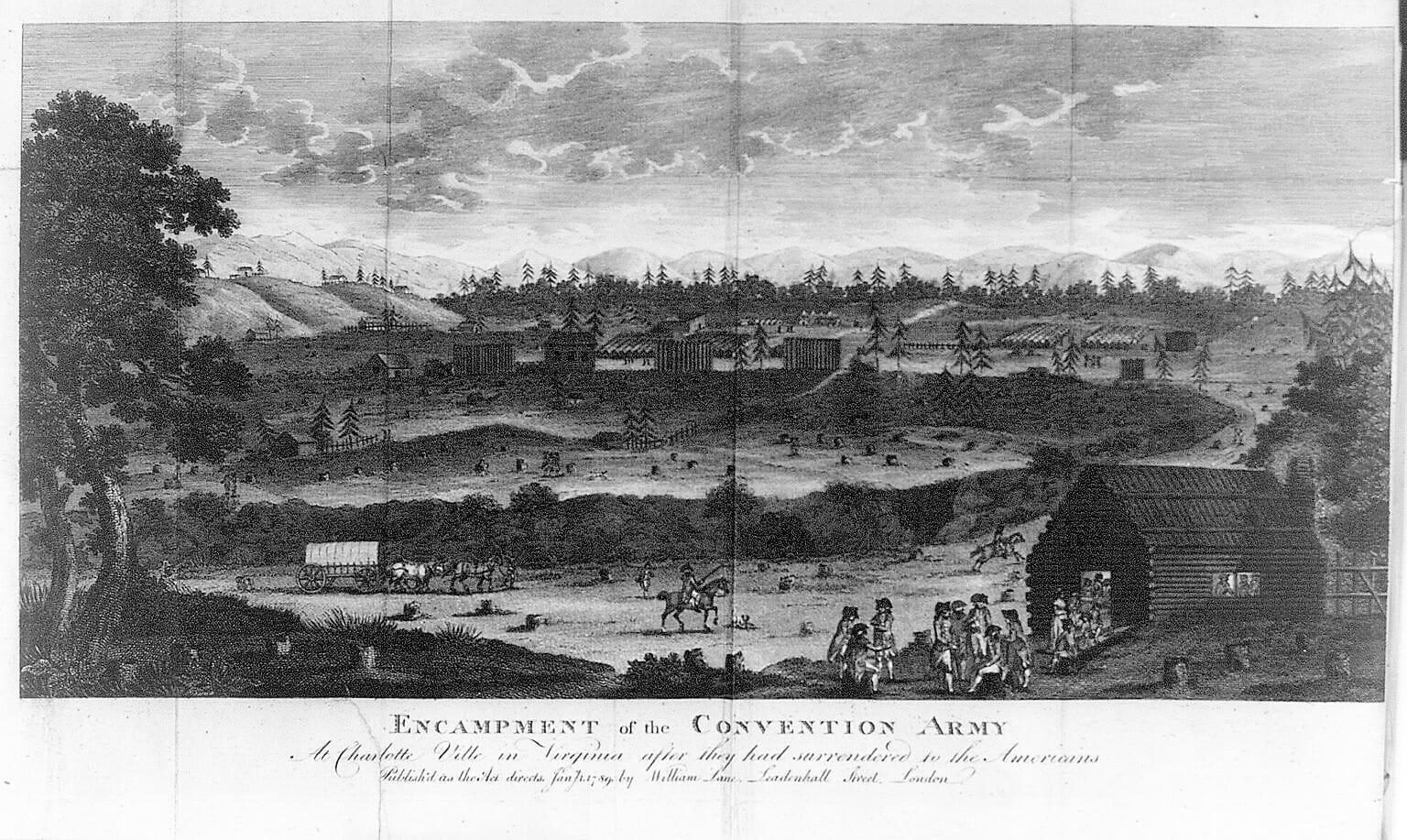

“The sight was not especially pleasant,” Von Selden wrote about his first glimpse of the prisoner barracks in a journal article published in 1839 in the German Journal for the Science of War. “A four-sided square 1,000 feet wide and long was surrounded by high stockades and equipped with two gates. In the interior were blockhouses, but only roughly built, for they had neither chinked the space between the logs nor installed windows nor doors, there was not even a fireplace in them, say nothing of any sort of household goods like tables, benches, etc. The weather was raw, wet and windy, our clothing, the most wretched in the world, but complaining did not help, everyone had to help himself as best he could.”

Von Selden and his fellow prisoners were labeled the “Convention Army” after their surrender was arranged through an agreement between British General John Burgoyne and American General Horatio Gates. Among the terms of the agreement, or convention, was that the British and German combatants would be marched to Boston and sent back to England after vowing never to return to the war against the Americans. Another 1,000 Canadians who fought alongside the redcoats were allowed to return to their homeland.

To the dismay of Burgoyne and Gates, the Continental Congress balked at the agreement to send the rank-and-file British and German troops home, stipulating that that part of the arrangement would not be honored without ratification by the British government. Unfortunately for the Convention Army, the British government had no intention of approving the deal, a move that would signal recognition of the U.S. as a legitimate nation rather than an unsavory rebellion consisting of murderers and traitors.

And thus began a yearslong odyssey for the Saratoga prisoners, held for a year around Boston, then marched to Virginia in the middle of winter 1778-79 and finally to Frederick, Maryland, in 1780-81 for the remainder of the war. By the summer of 1779, the Convention Army had lost about 2,000 men to death and desertion, about 1,000 of them after leaving Massachusetts.

The odyssey begins

Following Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga, the Convention Army offered the Continental Congress a chance for both retribution and leverage to gain better treatment of American POWs, according to the book, “Captives of Liberty: Prisoners of War and the Politics of Vengeance in the American Revolution,” by Purdue University history professor T. Cole Jones.

Before Saratoga, Jones explained, the Americans expected the British to conduct the war based on norms of European warfare, “in which conflict was carried out by nation-states with standing armies, regulated by discipline, and officered by gentlemen of honor who restrained the use of violence to the field of battle and humanely treated prisoners of war in its aftermath.”

However, the British violated those norms after the battles at Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill, overcrowding American prisoners into tight quarters, many aboard prison ships, where they suffered from inadequate food, clothing, sanitation and medical care, Jones wrote. Despite the prisoner abuse, the Americans continued to treat British and German, or Hessian, prisoners humanely in hopes of setting an example for better treatment of American POWs.

When hundreds of British soldiers were captured during the first significant campaign of the war, the American invasion of Canada in 1775-76, Congress “created a system of prisoner management largely consonant with European norms,” Jones wrote. “Through their treatment of British soldiers captured in Canada, American leaders conveyed a powerful message to both their antagonists and each other: though reduced to the necessity of taking up arms to obtain redress for their grievances, how they fought would reflect why they fought. ‘The Glorious cause of liberty’ had to be defended with honor and propriety.”

By the time Burgoyne and Gates signed their convention, Congress and the American public, which learned of British atrocities through newspaper accounts, had grown weary of the mistreatment of American prisoners.

According to Jones’s book, William Livingston, the first governor of New Jersey and a member of the Continental Congress, wrote in the New-Jersey Gazette under the pseudonym “Adolphus,” “The detention of Burgoyne and his army, until the Convention of Saratoga is ratified by the Court of Great Britain, is a measure founded on the truest policy and strictest justice.”

Reminding his readers of the plight of the Fort Washington garrison, Livingston asked how they could trust the British to uphold the Saratoga Convention when “three thousand freemen capitulate on condition of being treated as prisoners of war — but the moment their arms are out of their hands, they are treated as rebels, crowded together in the holds of transports or amidst the unwholesome damps of churches and suffered to perish with hunger and cold. … we have born their cruelty and frauds with a patience unparalleled in history.”

The only recourse Americans possessed was to treat the British as they deserved, “as robbers and murderers when they presume to treat us as rebels,” Livingston wrote.

The Convention Army spent a year in the Boston area before the arrangement became untenable, largely because Congress did not provide funding to care for the prisoners. Major General William Heath, “begged and borrowed enough food stuffs and necessities to keep the men from starving that winter, but by the spring of 1778, the general was absolutely at the end of his tether,” Jones wrote.

“From Congress’s perspective, provisioning the troops was not an American problem. Under the terms of the convention, the British were supposed to repay or replenish the supplies consumed by the prisoners.”

The detained prisoners also became a burden to the people of Boston. “While Boston merchants and Cambridge landlords had prospered from the British presence (officers were allowed to rent rooms and basically live free in town), most residents resented the hauteur of the convention officers and the relatively lax confinement of the enlisted men,” Jones wrote.

“Cavorting about the taverns of Cambridge, the paroled officers offended many Bostonians, while enlisted conventioners who escaped from the barracks were a constant source of frustration for American magistrates. As their detention dragged on, the soldiers suffered from the twin plagues of early modern armies: boredom and alcohol abuse.”

Even law-abiding conventioners presented a threat to the civilian population with smallpox and typhus spreading among the troops. Smallpox claimed more than 300 conventioners in spring 1778, Jones wrote.

With fighting ramping up around New York and the logistical hardships of keeping the prisoners in Massachusetts, Congress finally decided in fall 1778 to move the Convention Army to Albemarle.

On to Albemarle County

“Largely spared from the ravages of war, far removed from any British army, and already utilized to detain loyalist and Hessian prisoners, the interior of Virginia seemed to be an ideal location to confine and supply the conventioners,” Jones wrote. “There, the delegates reasoned, the men could be held until the British reformed their barbaric ways or a favorable opportunity for exchange presented itself.”

Reduced to 2,263 British and 1,882 German troops, the Convention Army began its march to Albemarle County on Nov. 9, 1778. The first division arrived in early January 1779, the remainder by mid-February.

“Despite ample time between the prisoners’ departure and their arrival in Charlottesville, “Jones wrote, “revolutionary officials in Virginia were entirely unprepared to house and feed the weary troops.”

Congress chose land offered rent free by John Harvie, a Virginia representative in the Continental Congress, for the barracks. “Hardly a philanthropist — he was in dire financial straits — Harvie realized that the prisoners would undoubtedly improve his land, thus increasing its resale value after their departure,” Jones wrote.

Congress also put commissary officer Captain George Rice in charge of building the barracks and provided him with $23,000. “With government cash lining his pockets, Rice departed for Charlottesville in little hurry to begin construction,” Jones wrote. “To their horror, instead of comfortable barracks the prisoners found a few log huts [that] were just begun to be built, the most part not covered over, and all of them full of snow.”

Von Selden wrote that the prisoners were ordered by the Americans to finish building the barracks. “So the troops were divided up and the work begun with all possible activity … everyone lent his hand to the job and within a few days the barracks had been fixed enough so that they provided some shelter from the weather.”

“Officers were allowed to build themselves houses at their own expense or to move to the town of Staunton, 42 English miles from the barracks, but only a few took advantage of this,” Von Selden wrote. “The others preferred to build themselves small houses outside the barracks after giving their word of honor that they would not leave a certain prescribed area.

“Since I also wished to live separately, I was allowed to do so, for which purpose I found a suitable spot in the woods, which was located on a small hill half an English mile away. The house was to be 14 square feet in size with a garden 110 feet long and 60 feet wide.”

Despite their rough beginning, the prisoners generally fared better in Albemarle County than in Boston.

Christa Dierksheide, professor of history at UVa, said in an email that some Convention Army officers rented area mansions. “For example, Baron (Friedrich Adolf) Riedesel rented Colle, which was adjacent to Monticello.”

As for the enlisted men, Virginia’s newly elected governor, Thomas Jefferson, “believed that treating captives with politeness and generosity not only mitigated the horrors of war, but also was the accepted practice among modern nations,” Dierksheide said. “Since the new United States desperately wanted to be considered a modern nation by a candid world, it was important that the prisoners in Charlottesville not be allowed to starve or be physically harmed in any way.”

Although conditions in the camp improved in 1780, it became imperative that the captives be moved ahead of the British invasion of the Carolinas and Virginia in 1780-81, Dierksheide said. “Jefferson feared that the prisoners would hear of the British attack and try to join those forces.”

Jones wrote that the relocation to Frederick was alarming to the conventioners. “The British prisoners had worked tirelessly to make their quarters at Charlottesville habitable, while the Germans, whom the revolutionaries deemed less of a flight risk, had enjoyed the freedom of working and lodging with local farmers.”

Once the Convention Army departed, evidence of their stay rapidly disappeared, wrote Phlander D. Chase in a 1983 article in “The Magazine of Albemarle County History.”

“A Continental harness factory staffed by several German prisoners who had been left behind operated at the barracks during the spring and summer of 1781, but following Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown in October, it was apparently closed,” he wrote. “Sometime thereafter the crude log buildings vanished, either decaying naturally or being pulled down by local inhabitants seeking building materials or firewood. … Only the name ‘barracks’ survived in the area, being applied to a handsome nineteenth century house that was erected near the site of the Convention Army’s main encampment and to the road that winds its way west from Charlottesville to Ivy Creek.”

Not far from where the children are playing and the neighbors are chatting, a pair of historic markers stand as reminders of the Convention Army barracks and a graveyard for those who died there.