The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

If you think moving is an ordeal in the age of the interstate, imagine moving in the 18th century when oxen pulled wagons over mud-choked roads at two miles per hour.

Patrick Henry didn’t mind. A relative said, “He regarded as nothing the trouble of moving, and would change his dwelling with as little concern as a common man would change his coat of which he was tired.”

Some of his many moves — more than a dozen over his lifetime — were required by his service as governor. But it’s also true that he just liked to move. As an adult he rarely stayed anywhere more than five years or so.

Henry lived in 13 different places — 14 if you include two different buildings at Pine Slash Plantation in Hanover County, according to Mark Couvillon, author of “Patrick Henry’s Virginia.” The Revolutionary firebrand owned seven plantations in his lifetime, and also lived in childhood homes, rentals and governor’s residences.

Only two of his homes still stand: Scotchtown and a building at Pine Slash, both in Hanover County. Red Hill, in Charlotte County, is a reconstruction. Some home sites and other landmarks associated with Henry are marked by colorful Road to Revolution plaques, per a 2012 directive from the General Assembly, of which he was an early member, and/or by silver-and-black state historical markers or other displays. The plaques form a trail across southern and central Virginia, from the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg to Louisa County to the Leatherwood site east of Martinsville.

“It seems like he was always trying to find that perfect spot,” Couvillon said in an email. Sometimes Henry had additional, family reasons for moving — he bought Scotchtown hoping to relieve his wife’s depression, and moved his family to Leatherwood in 1779 partly to escape wartime upheavals in eastern Virginia.

Still, “having so many homes was unusual for the time, due in part to the trouble of traveling on 18th century roads, as well as getting all of one’s possessions, farm implements, livestock and enslaved from one place to the other,” Couvillon said. Most Founders lived in only one to three homes in their lifetime.

Scotchtown was spacious for the times, but Henry deliberately refrained from building a grand hilltop estate like Washington’s Mount Vernon or Jefferson’s Monticello.

Henry “was not drawn to the latest fashions or trends when it came to food, furniture, dress, or architecture,” Couvillon said. “Furthermore, he saw many of his friends and family members (including his father and brother) riddled by debt to local and British merchants and he did everything he could to prevent the same from happening to his family. He always tried to live within his means, and unlike Jefferson, he was able to clear himself of debt before he died and did not pass it along to his children.”

Most of Henry’s homes were simple and practical with little ornament, suiting a plain, practical politician and man of the people. The remote locations reflected his love of nature and freedom. Henry was said by one contemporary to “prefer Country living to the restraints of polished society.”

Patrick Henry Jolly, a fifth- and sixth-generation descendant of the orator (more on that later), is a researcher and tour guide at Red Hill.

“He was a very modest individual,” Jolly said of his ancestor. “He was very frugal, and he didn’t need to express himself by his dwelling place — ‘look at me, this is what I am, this is what I’ve accomplished.’ And I’m not trying to criticize any of the other Founders and their homes. But Patrick Henry is not like these other guys.”

Patrick Henry will never be forgotten — “Liberty or Death” ensures that — but he’s less remembered than his peers who became president, partly because he never served in that office, and also because no single estate serves as a monument on the scale of Mount Vernon or Monticello.

On the other hand, the geographic range of his homes means much of the state’s population is within a Saturday drive of one of his homes or home sites. They help bring to life a Virginian famed for his ringing voice, but less known for what Couvillon calls his “itchy foot.”

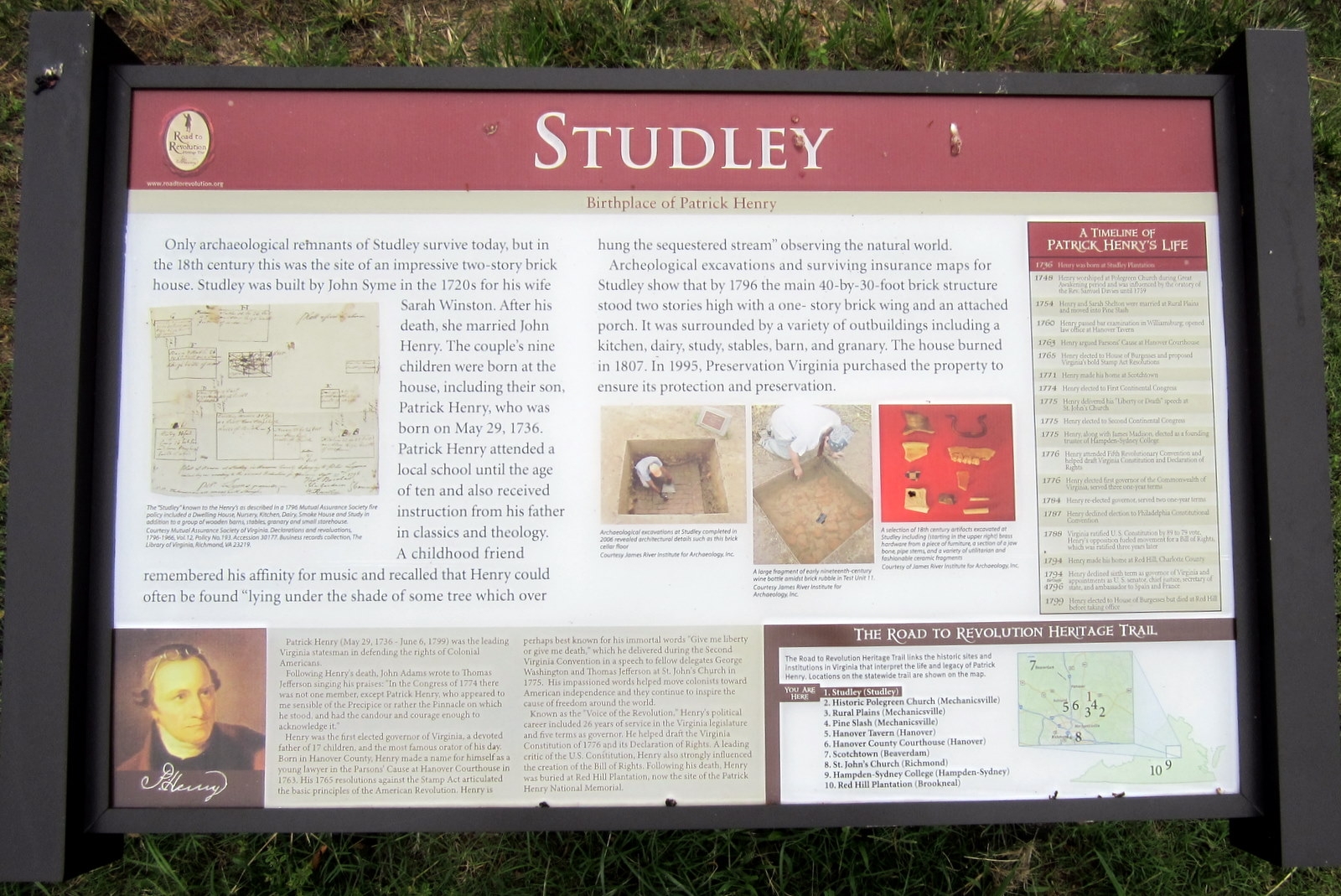

1736 — Studley, Hanover County

Studley was built in the 1720s by John Syme for his wife, Sarah Winston. After Syme died, she married John Henry, Patrick’s father. Patrick Henry was born here on May 29, 1736. The 40-by-30-foot brick house had two stories, a porch and a one-story brick wing. It burned in 1807, the fate of most homes associated with Henry. Preservation Virginia bought the site in 1995. Today, only archaeological remnants remain. A Road to Revolution plaque at the end of Studley Farms Drive marks the spot.

Around 1750 — Mount Brilliant, Hanover County

When Patrick Henry was 14, Studley was turned over to his stepbrother John Syme, Jr., and John Henry moved his family to Mount Brilliant, built by John Henry in remote, western Hanover County. Mount Brilliant was a one-and-a-half story house on a brick foundation, with dormer windows. Here, Patrick enjoyed hunting, camping in the woods, fishing, and swimming in the South Anna River.

“Patrick’s carefree days at Mount Brilliant were short lived,” Couvillon wrote in “Patrick Henry’s Virginia.” At age 15 his father put him to work clerking for a shopkeeper.

The house was probably dismantled in the early 19th century. Only a depression in the earth and some brick fragments remain.

1754 — Pine Slash, Hanover County

When Patrick Henry married 16-year-old Sarah Shelton in 1754, her dowry was 300 acres in eastern Hanover County and six enslaved persons. Like other small farmers, Henry worked the tobacco fields alongside his slaves. An early biographer described the future governor as a “young rustic at work in the coarse garb of a laborer, covered with dust and melting in the sun.”

In 1757, the main house burned, and the family, with two small children, moved into a building now called the overseer’s cottage, one of two original Henry homes still standing. The Henrys lived here for about six months. It is approximately 60 by 20 feet, one story, with three rooms on the ground floor, an attic and a half cellar.

The Road to Revolution marker for Pine Slash can be seen on Rural Point Road in eastern Hanover County.

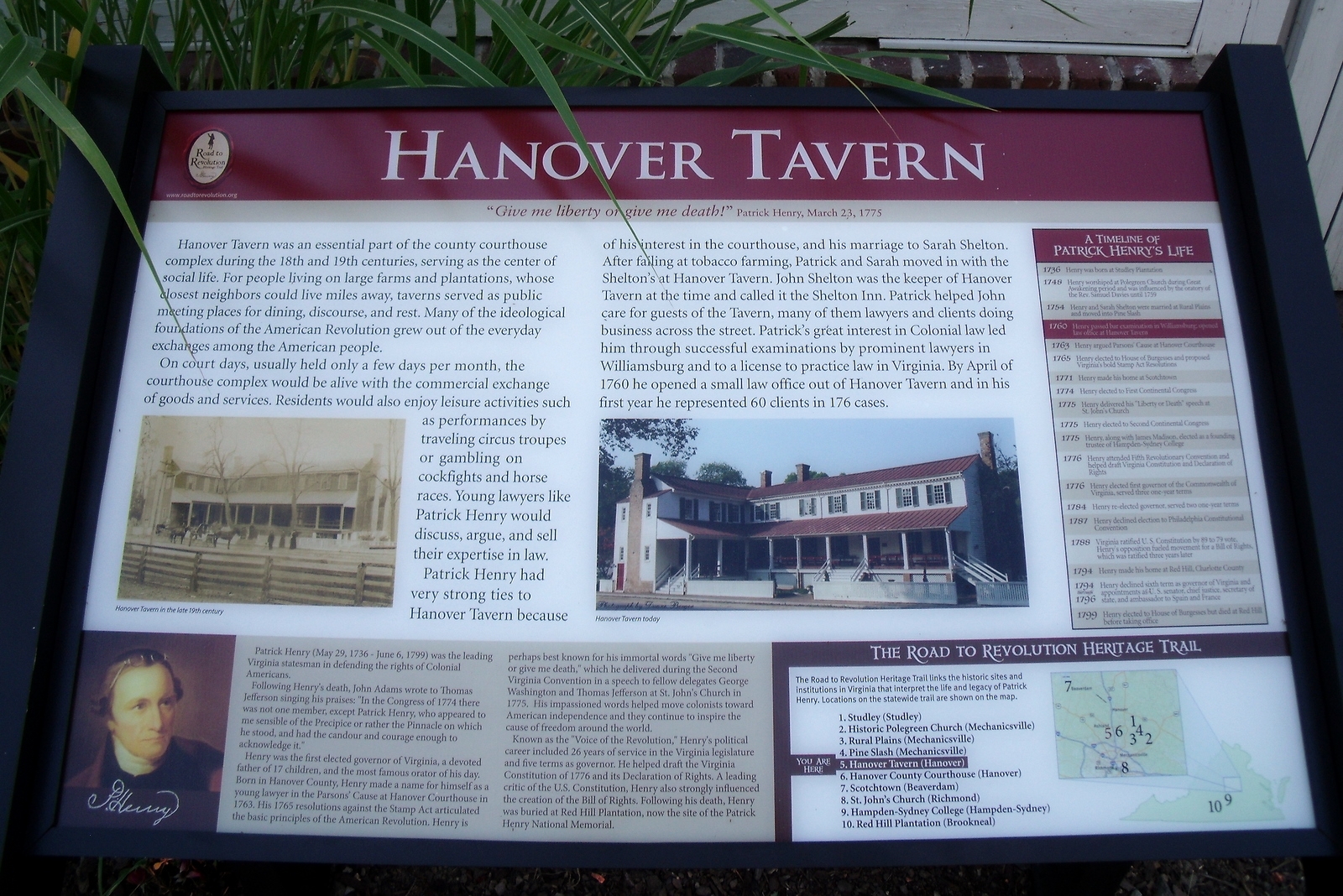

1757 or 1758 — Hanover Tavern, Hanover

The family moved to Hanover Tavern, owned by Sarah Henry’s father John Shelton. Patrick Henry helped provide hospitality to tavern guests. Talking with lawyers and judges, Patrick Henry made the critical decision to study law. He obtained his law license in 1760.

The original tavern no longer exists. A Road to Revolution sign and silver-and-black historic marker are located near the present tavern and courthouse. The exact location of the Henry-era tavern is uncertain, according to Couvillon.

1765 — Roundabout, Louisa County

Henry’s father-in-law, John Shelton, sold Hanover Tavern in 1764. Patrick Henry had a new house built on 1,700 acres in Louisa County on Roundabout Creek. During this period Henry first gained national notice as a new member of the House of Burgesses, representing Louisa. On May 29, 1765, his 29th birthday, he gave an electrifying speech attacking the Stamp Act, comparing King George III to Julius Caesar and Charles I — both of whom lost their lives amid accusations of tyranny.

The Henrys moved into Roundabout by the end of 1765. It was remembered by a local resident as a story-and-a-half structure about 18 by 20 feet. The closest neighbor was two miles away. In 1768, Henry had ten slaves who tended about 30 acres of tobacco.

Roundabout burned around 1920. In 1976, a stone marker was placed at the location, about eight miles south of the town of Louisa.

1771 — Scotchtown, Hanover County

Scotchtown — the origin of the name is unclear — was built around 1719 by Charles Chiswell. It passed through the hands of Charles’s son John and John Chiswell’s associate John Robinson (see our story on Chiswell’s lead mines) before Patrick Henry acquired it.

The “largest and grandest of all Patrick Henry’s homes (except the Governor’s Palace at Williamsburg),” according to Couvillon, it was described in one of the Virginia Gazettes (see our story) in 1769 as a “large commodious dwelling-house built of wood with eight rooms on one floor … all convenient outhouses, also a good water grist mill; and there are three plantations cleared sufficient to work 20 or 30 hands, under good fences, with Negro quarters, tobacco houses, etc.”

Couvillon writes:

“Despite these advantage, Patrick Henry’s purchase of the stately manor house seems somewhat out of character for the plain-living man. Although he picked up Scotchtown for a bargain — a little more than £600 — the main reason for its purchase was his wife, who suffered from what began as a severe post-partum depression. Henry hoped that a change of scenery would restore her failing health, but unfortunately, it was not to be. According to family tradition, Sarah Henry became so unstable at the end of her life that she had to be confined ‘in one of the airy, sunny rooms in the half basement’ used as the servants’ hall.'”

The son of the family physician recalled that while Henry was “rousing a nation to arms, his soul was bowed down and bleeding under the heaviest sorrows and personal distresses. His beloved companion had lost her reason, and could only be restrained from self-destruction by a strait-dress.”

Sarah died in 1775, just weeks before Henry gave the Liberty or Death speech at St. John’s Church in Richmond that secured his undying fame.

Henry was elected first governor of the new Commonwealth of Virginia in June 1776. While living at the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, he occasionally returned to Scotchtown. But memories of Sarah haunted him, and he determined to leave the setting of her agony. He sold Scotchtown in 1778 for £5,000.

Scotchtown was acquired by Preservation Virginia in 1958 and is the only original standing home of Patrick Henry open to the public. For more information, see Preservation Virginia.

1776 — The Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg

The first governor of newly independent Virginia moved into the ornate Governor’s Palace lately vacated by Lord Dunmore, last in a long line of royal governors. Built in the early 18th century, by Henry’s time it had gardens, an orchard, offices and a ballroom.

During his second term as governor, in 1777, Henry married Dorothea Dandridge, granddaughter of Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood, of “Knights of the Golden Horseshoe” fame. Dorothea, 22, became first lady and stepmother to six children. In 1778, she gave birth to the first of the couple’s 11 children.

Couvillon writes:

“As the first elected governor of Virginia, Patrick Henry strove to maintain a dignified air at the Palace. He knew that some of Virginia’s gentry believed he was going to ‘make a mockery out of that once exalted position.’ Henry was determined to prove them wrong, and ‘he assumed a Dignity of Demeanor which commanded the Admiration of all.'”

The Henrys left the Palace after his third term ended in 1779. On Dec. 22, 1781, the building burned down, leaving a pile of rubble. The Palace in present-day Williamsburg is a reconstruction. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation offers public tours.

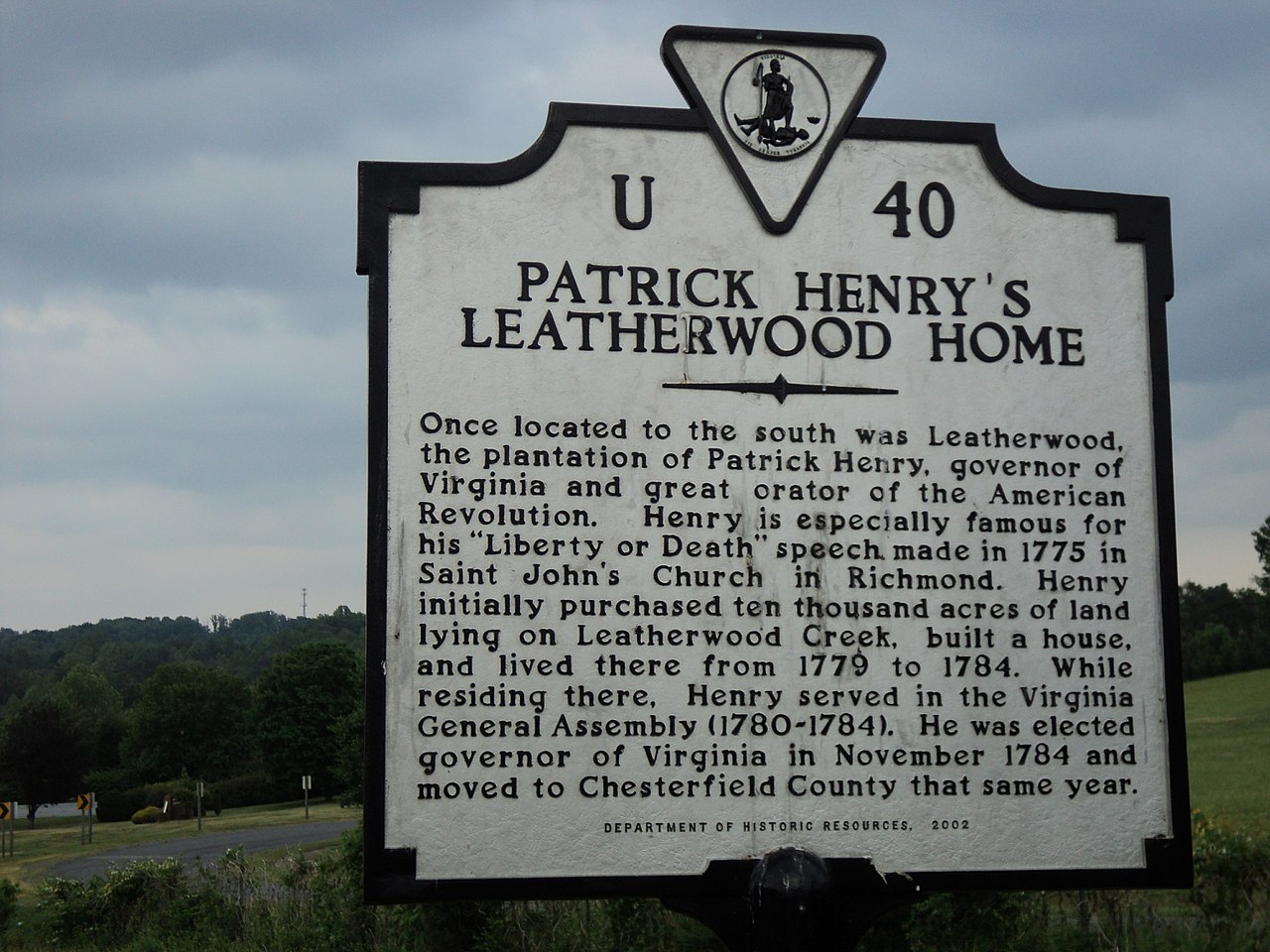

1779 — Leatherwood, Henry County

In May 1779, a British fleet raided the Chesapeake Bay, destroying ships, military supplies and tobacco. After Henry’s third term ended on June 1, 1779, he rounded up his wife, children, enslaved persons and livestock for the 190-mile trek west to the county recently named for him. He wanted to protect his family from danger in the east, and also hoped the cooler air and country living would restore his stressed nerves.

Their new home was a 10,000-acre plantation, Leatherwood, in Henry County near Martinsville. More fitting than the Governor’s Palace for a plain-living man, their new home was a simple two-room brick house. But Henry could not stay away from politics. He was elected to the General Assembly and left a manager to run the plantation in his absence.

The house stood until about 1870. The location is marked by a silver-and-black sign on U.S. 58 east of Martinsville.

1784 — The Governor’s Mansion, Richmond

Henry was elected to his fourth term as governor in 1784. The state capital had been moved to Richmond in 1780. The Governor’s Mansion was east of the new Capitol, then under construction. Samuel Mordecai, an early Richmond historian, described the grandly named “Mansion” as “a very plain wooden building of two stories, with only two moderate sized rooms on the first floor. It was for many years unconscious of paint…” The fence was dilapidated and goats grazed on His Excellency’s grounds. John Tyler considered it “intolerable” as a family home.

Still, the Henrys received some distinguished visitors. Couvillon writes:

“One of the notable guests to the mansion was George Washington, who dined with the Henrys on May 1, 1785 … After his visit, Henry’s daughter described General Washington as ‘grave’ — he ‘did not laugh’ while her father on the other hand, was ‘a great laugher.'”

The “Mansion” no longer stands.

1785 — Salisbury, Chesterfield County

Henry did not like urban life and the Governor’s Mansion was in any case too small for his large brood. During his fourth term as governor, the Henrys moved to Salisbury in Chesterfield County about 14 miles from Richmond. Built between 1760 and 1780, the house was 56 by 40 feet, one and a half stories, with a hip roof, basement, and large, airy rooms. The Henrys rented the house from Thomas Mann Randolph. The state provided the governor with a coach, but Henry preferred to commute to the Capitol on horseback, sometimes with a child or two in front or behind.

Salisbury burned in 1923. A state historical marker is on West Salisbury Road in Midlothian.

1786 or 1787 — Pleasant Grove, Prince Edward County

After completing his fifth term as governor, Henry could have returned to Leatherwood but elected to uproot again. This time he bought a two-story frame house in Prince Edward County about a mile south of the Appomattox River. He left most of his enslaved persons and livestock at Leatherwood and re-started his law practice. During the Pleasant Grove years, the lover of liberty fought for the adoption of the Bill of Rights.

Like so many of Patrick Henry’s homes, Pleasant Grove later burned down. Perhaps that is a fitting fate for the home of a firebrand, but on the other hand, in an era when domestic heat and light came from open flame, lots of houses burned down, whether or not they were the home of a firebrand.

Pleasant Grove stood on Virginia 645 about a half mile north of U.S. 460.

1792 — Long Island, Campbell County

Still seeking the perfect spot, in 1792, Henry put Pleasant Grove up for sale and moved his family to an estate in Campbell County which he bought from Light-Horse Harry Lee. The property was named for an island in the Staunton River. The house stood on a bluff on the Campbell County side with a fine view of the river and Pittsylvania and Halifax counties. It was another simple one-and-a-half story house. Henry continued to practice law and raised livestock and crops.

“Out of politics and almost clear of debt, Patrick Henry was able to enjoy some well-deserved rest at Long Island,” Couvillon writes. The great orator now composed poetry. He no longer hunted, but built a fish trap, where he once accidentally caught a deer. The prolific paterfamilias still had the energy to sire his fifteenth child, Winston.

After buying his next, and last house, Red Hill, Henry continued to manage Long Island with the help of an agent.

The house met the usual fate, burning in 1930. The site is on Long Island Road near Brookneal.

1794 — Red Hill, Charlotte County

The peregrinations of Patrick Henry came to an end at Red Hill. Built in the 1770s, Red Hill was another simple story-and-a-half frame building. A kitchen and law office stood nearby. Henry built a watch-tower (no longer standing) from which he could view the tobacco and wheat fields sloping down to the Staunton River. “Though old and infirm, his voice was still strong enough that he was able to give orders to his slaves at work in the fields more than a half-mile distant,” Couvillon wrote.

Even though he grew tobacco, the aging farmer did not like the smell of it and wouldn’t let people around him smoke.

Patrick Henry Jolly believes Red Hill housed eight children and a nephew, plus Patrick and Dorothea. “One visitor said when people arrive at Red Hill, it’s not unusual to find him on the ground with kids and grandkids just crawling all over him, playing around, just seeing who can make the most noise.”

The man born at Studley ultimately produced 17 children and 77 grandchildren. Patrick Henry Jolly is descended from both Martha and Elizabeth Henry, daughters of Henry and his first wife, Sarah Shelton Henry. One of Martha’s grandsons married Elizabeth’s youngest daughter. This makes Jolly a fifth- and sixth-generation descendant of Patrick and Sarah Henry, through Jolly’s mother.

Patrick Henry got both liberty and death. The voice that rattled a king and shook an empire fell silent on June 6, 1799. He died of an intestinal blockage at 63 and rests under a slab with the inscription, “His fame his best epitaph.” Dorothea died in 1831 and was buried next to him. The man of the people is not behind a protective fence. Ordinary people may touch his tomb if they like.

Red Hill met the usual fate of Henry’s homes in 1919.

The site is owned by the nonprofit Patrick Henry Memorial Foundation. In 1986, Congress designated Red Hill as the Patrick Henry National Memorial.

Red Hill does not receive federal funding, and is supported by admissions, donations and grants, said Takisha Fowlkes, at the time of the interview the director of community engagement & programming. Events include school tours and naturalization ceremonies.

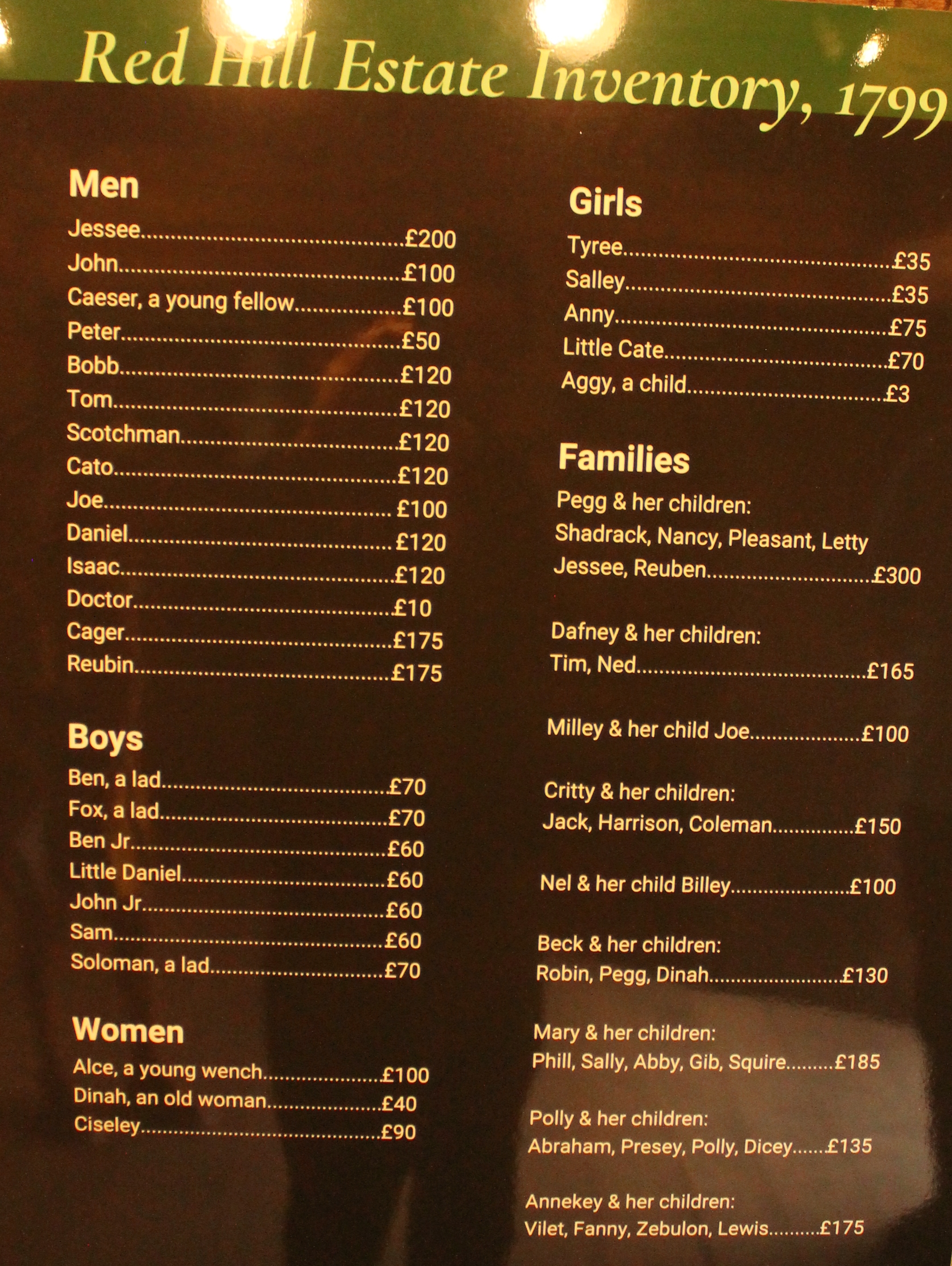

The lifestyle of Henry and the other Founding Fathers of Virginia was made possible by the people they enslaved. After Henry’s death, an inventory recorded more than 60 enslaved people. The Quarter Place Trail at Red Hill memorializes their lives with a reconstructed slave cabin and historical displays. The Quarter Place cemetery is the final resting place of the enslaved people who worked at Red Hill and their descendants, including those still living on the plantation when liberty finally came in 1865. Only one of the 147 graves has a tombstone with a name on it, Matilda Pannell. Research has identified the names of more than 50 others.

Red Hill and the fields and forests around it remain serene and untouched by development, which would have pleased Patrick Henry, a man who made his name speaking to crowds in stuffy buildings, but who preferred the fresh air of the open countryside.

The Red Hill site, including reconstructions of the main house and the slave cabin, is open to visitors. See https://www.redhill.org/

Much of this article is based on “Patrick Henry’s Virginia: A Guide To The Homes and Sites in the Life of an American Patriot,” by Mark Couvillon, published 2001 by the Patrick Henry Memorial Foundation.

The moving story of Patrick Henry’s law office

It is perhaps fitting that the law office of Patrick Henry, a man who liked moving, has itself been moved more than once, and might be moved again.

The building was part of the Red Hill property when Henry purchased it in 1794, according to Red Hill archaeologist Lucia Butler.

“When Henry’s great-granddaughter, Lucy Harrison, owned Red Hill in the early 20th century, she had the office moved farther south to stand between the house and the family cemetery,” Butler said in an email.

“The office was moved once again when the Patrick Henry Memorial Foundation made efforts in the 1950s and 60s to restore Red Hill to its 18th-century appearance — this included moving the law office closer to its original site.” The building couldn’t be put back in place because a state highway circled the grounds.

“The highway is now gone, allowing archaeologists to investigate the original site,” Butler said. “Red Hill’s archaeological team and our volunteers are searching for any traces of the building in its original location, including foundations, builder’s trenches, and associated artifacts. This will help us confirm the original location and preserve any of its remains in place.”

If the foundation ever decides to move the building again, Butler said, the results will help guide the relocation.