If the year’s atmospheric flow is a river, we have entered some slow, lazy, sandbar-laden shoals as we move into the heart of summer.

It might seem odd to mention sluggish water and sandbars if your spot on the map has been caught under a downpour in recent days, which many have at least briefly, and some to the point of flooded roadways and swollen streams. More like fast-running drainage and mud for you. Others have missed most of the heavier storms and may still have some drier dirt around.

The jet stream, where the fastest upper-level winds flow, has retreated to just above the U.S.-Canada border, which is not unusual. It usually parks somewhere near there in mid-summer.

It is flowing almost directly west-to-east, called a “zonal flow,” which means no big ridges or dips that would lead to extreme temperatures or especially changeable weather.

The result for the Southwest and Southside Virginia coverage area of Cardinal News has been a daily repeating pattern of stickiness and storminess since late June, minus a few days right around the Fourth of July, conveniently. That general pattern shows no signs of changing in the foreseeable future, which in weather is something on the order of 5-10 days.

The upper-level winds guiding the atmospheric flow across the contiguous 48 states are mostly very weak. Subtle systems move slowly, weak fronts get stalled. These features help focus moisture convergence and atmospheric lift for the thunderstorms we have seen pop up just about every afternoon lately. And with weak winds aloft, the storms don’t move far or fast, often raining themselves out in one place while someone else a few miles away gets maybe a few sprinkles.

Mostly, though, it is each day’s heat and humidity that leads to storm formation, influenced also by the region’s mountainous terrain that provides lift from weak wind flow up the ridges and also boundaries where air of differing temperatures focus. Also, the outflow from thunderstorms that have collapsed creates boundaries along which new storms form.

None of this is especially unusual. It happens to at least some degree every summer.

What is somewhat different is the density of thick moisture that overspread much of the eastern two-thirds of the nation in late June, with unusually high dew points and precipitable water values (how much moisture there is to wring out in the atmosphere) very far north.

Beyond the acute nature of this occurrence in summer 2025, there has been a chronic pattern of greater moisture spreading more inland and more northward from warming oceans in recent decades. How this has had an upward nudge on our regional summer low temperatures is a topic worth exploring on its own sometime soon.

That thick moisture quickly rebounded over our region after the Fourth of July dry break, partly aided by the arrival of the remnants of Tropical Storm Chantal.

So we are in the soup of daily almost beach-like stickiness, with dew points above 70 common, especially east of the Blue Ridge. The water vapor in the air brought to a roiling boil each afternoon by mid 80s to lower 90s high temperatures. OK, not literally a boil, as that would require temperature of 212 degrees Fahrenheit, but the towering cumulus clouds poking high in the sky as updrafts of warm moisture rise into colder air high above us do give the appearance that they are boiling.

Some locations have seen, and will see, localized flooding (2-3 inches of rain in an hour) and gusty winds (near 60 mph) in the worst of the storms. Even the storms that aren’t so bad may shoot out dangerous lightning, sometimes many miles away from the core of the storm. (See the next section of this column.)

Long term there may be a slight move toward somewhat hotter and perhaps a bit drier weather late in the month as high pressure builds over the south-central U.S. and perhaps expands eastward. But there is also a potential tropical system near the Gulf Coast in the next few days that could throw a wrench into things. And if the high sets up west of us, it could sling squall lines toward us from the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley.

Nothing is going to change very fast with the lazy flow of air above us.

Bolt from the blue

A few weeks ago in this space (linked here), we covered the topic of lightning, some general safety tips for reducing your chances of being struck, and some discussion of how lightning can strike many miles outside the rain core of a thunderstorm.

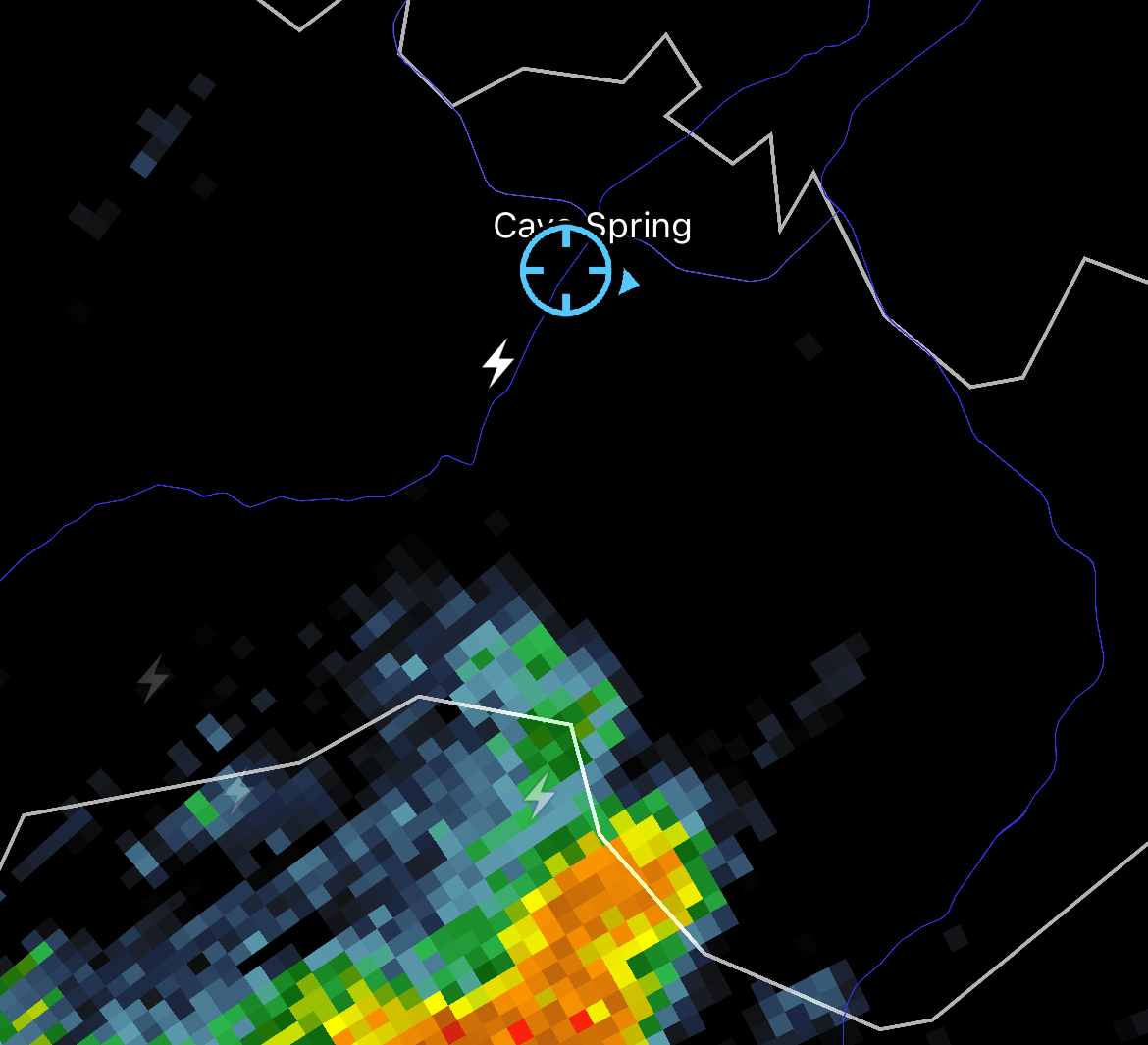

On Monday night, July 14, a house was struck by lightning in a hilltop neighborhood in the Cave Spring area of southwest Roanoke County, even though the parent storm from which the lightning sprang was about 10 miles south in northern Franklin County. Quickly responding firefighters were able to contain the fire in 10 minutes and put it out in 20 minutes, and two people in the house were uninjured.

I was within a mile of this lightning strike, outside of an automobile pumping gas. There was a bright flash and then a huge concussive blast of thunder, which honestly rattled me quite a bit, as there was no indication close lightning was likely to occur. There had been no previous close bolts of lightning since a prior storm had passed through two hours before, and apparently no close bolts to this area after this one strike.

It was an apt reminder of how dangerous lightning can be even when the storm isn’t overhead, and a deeper reminder of our individual powerlessness compared to nature.

Journalist Kevin Myatt has been writing about weather for 20 years. His weekly column, appearing on Wednesdays, is sponsored by Oakey’s, a family-run, locally-owned funeral home with locations throughout the Roanoke Valley. Sign up for his weekly newsletter: