When former Tazewell County and Ferrum College star Billy Wagner joins the Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday, he apparently will become just the sixth Virginian to be enshrined in Cooperstown.

Here are the others and their Virginia connection. Four of the five were stars in the Negro League.

Ray Dandridge

1913-1994

Born in Richmond

Dandridge had a chance to break the color line in Major League Baseball but turned down the opportunity, thus opening the way for Jackie Robinson. A third baseman, Dandridge was considered a spectacular fielder. Future Hall of Famer Monte Irvin said that Dandridge was the best he’d seen and that Dandridge rarely committed more than two errors per season.

As a child, Dandridge often lacked a formal bat and ball, so he fashioned the former out of a tree branch and the latter out of a golf ball wrapped in string and tape. When he was 20, he went pro, starting with the Indianapolis ABCs in the old Negro League in 1933 and later with the Nashville Elite Giants, the Newark Dodgers and Newark Eagles. Feeling underpaid by the Eagles, Dandridge moved to Mexico and played nine years for Mexican League teams. Bill Veeck contacted him about signing with the Cleveland Indians in 1947, but Dandridge declined because he felt he was well-paid and treated with respect in Mexico. By the time baseball was more fully integrated, Dandridge was considered too old. He finished his career in the minor leagues, batting .360 in his final season in 1955 at age 42. He later worked as a scout for the San Francisco Giants and was inducted into Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987.

Leon Day

1916-1995

Born in Alexandria

Day was considered one of the greatest pitchers in the Negro Leagues, starting with the Baltimore Black Sox in 1934 and ending with the Baltimore Elite Giants in 1950; although he continued on in minor leagues and semi-pro leagues until 1955. The Pittsburgh Courier, an institution in the Black press of the day, twice ranked Day as a better pitcher than the famed Satchel Paige — for the 1942 and 1943 seasons. In 1942, he set a Negro League record with 18 strike-outs in a single game. Although he was a pitcher, Day was an everyday player who, on non-pitching days, played every position except catcher (although he was usually a second baseman or centerfielder).

Day’s career was interrupted by World War II. Drafted in 1943, Day went ashore in Normandy six days after D-Day as a truck driver. He was discharged in March 1946 and by Opening Day on May 5, was back on the mound. Although he hadn’t played professionally in three years, he threw a no-hitter in his first outing. Records from the Negro League are incomplete, but some believe Day won more than 300 games as a pitcher — something only 24 pitchers in the Major Leagues have done. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1995, six days before his death.

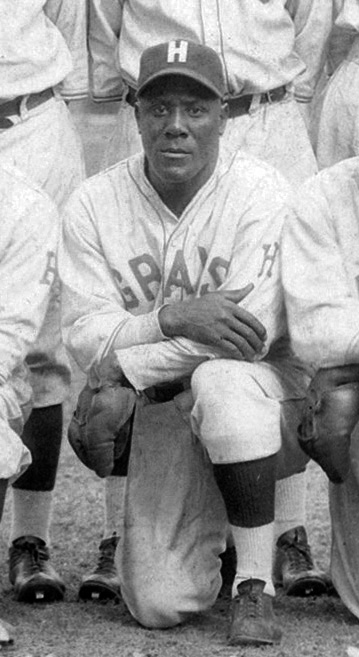

John Preston “Pete” Hill

1882-1951

Born in Culpeper County

Hill was another Negro Leagues player, starting with the Pittsburgh Keystones in 1899 and ending with the Baltimore Black Sox in 1925. Some years, he also played winter ball in Cuba. A 1952 poll by the Pittsburgh Courier, a leading Black newspaper, ranked him as the fourth-best outfielder in the Negro Leagues. His gravestone declares him “a standout centerfielder with a rifle arm” and the “Negro Leagues’ greatest deadball era hitter.” Historian William McNeil called him “Black baseball’s first superstar.”

He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Hill’s gravesite in Alsep, Illinois, originally had no marker until the Society for American Baseball Research paid to have one placed.

Eppa Rixey

1891-1963

Born in Culpeper County

Rixey played 21 seasons for the Philadelphia Phillies and Cincinnati Reds between 1912 and 1933. A pitcher, he had more wins than any other left-hander in the National League until the legendary Warren Spahn passed him in 1959. He also held the record for the most seasons pitched by a left-hander in the National League until Steve Carlton in 1986.

Rixey was also responsible for a new rule in baseball: Umpires can’t be involved in signing players. That came about because Cy Rigler, a Major League umpire who worked in the off-season as an assistant baseball coach at the University of Virginia, took the lead in getting his nephew signed with the Phillies. At the time, Rixey was a student at the University of Virginia and a star on the baseball team. Rixey initially wasn’t interested, saying he preferred to pursue a career as a chemist. However, Rigler sweetened the deal by promising to split whatever finder’s fee he got from the Phillies. Rixey took the deal, but Rigler never got a finder’s fee.

Rixey finished with 266 career wins. One former Cincinnati catcher called Rixey “the most outstanding player I came in contact with in my entire career.” Rixey was also unusual for his time in other ways. He came from a well-to-do background — his father was a banker, one uncle had been a congressman, another the U.S. Surgeon General. Rixey attended a university planning to be a scientist. During the off-season, Rixey returned to the University of Virginia to earn master’s degrees in chemistry and Latin. Later, he taught Latin during the off-season at Episcopal High School in Alexandria. “Rixey’s background and education were enough to set him apart from the average ballplayer, but he went a step further, writing poetry in his spare time, particularly enjoying sonnets and triolets,” writes the Society for American Baseball Research. “Although ballplayers resented college men, he gained their respect by holding his ground when they initiated him.”

Despite his background, Rixey was sometimes portrayed as a rube by sportswriters. He was known for his dry wit and his Southern drawl, which prompted a Philadelphia scribe to nickname him “Jephtha,” a name that stuck with him so much some thought it was his actual name. Asked once about his success, Rixey replied: “How dumb can the hitters in this league get? I’ve been doing this for fifteen years. When they’re batting with the count two balls and no strikes, or three and one, they’re always looking for the fastball and they never get it.” When he was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1963, Rixey said: “They’re really scraping the bottom of the barrel, aren’t they?”

After his retirement, Rixey became president of an insurance company in Cincinnati. He was the first Virginian named to the Hall of Fame. He was also the first inductee to die between his election and his scheduled installation.

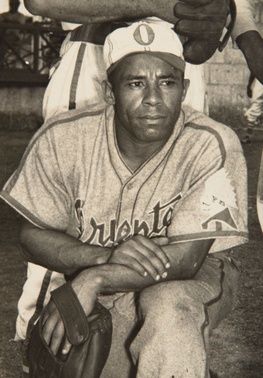

Jud Wilson

1894-1963

Born in Remington (Fauquier County)

Little is known about Wilson’s early life except that he served in the Army during World War I. In 1922, he signed with the Baltimore Black Sox and wrapped up his career in 1945 at the age of 49. By then, he was playing with the Homestead Grays, a Negro League team that sometimes played in Pittsburgh, sometimes in Washington, D.C. During the winters, he sometimes played in Cuba.

A power hitter, Wilson was quickly dubbed “Babe Ruth Wilson,” although later he acquired the nickname “Boojum,” because that was said to be the sound of his hits when they smashed into the outfield wall. Satchel Paige once said that Wilson and Chino Smith, another Negro League star, were the hardest to get out. Another Negro League legend, Josh Gibson, claimed that Wilson was the best hitter he’d ever seen. His lifetime batting average in the Negro League was .345 (for non-baseball fans, that’s very high). In the winter Cuban league, .372 (higher yet). He played first base, third base and sometimes managed.

Wilson was also known for his short temper and willingness to resort to physical violence. An entry in the Negro League Baseball Players Association website describes Wilson this way: “Wilson was feared as a hitter and was known for his willingness to fight, any time, anywhere.” His best friend said Wilson especially despised umpires: “The minute he saw an umpire, he became a maniac.” Once, when a teammate coming into their shared room late one night woke Wilson up, he grabbed the fellow player, took him to the window and he held him by one leg, dangling 16 floors up. There’s also a story about how Wilson once broke up a knife fight in the showers.

After he retired, Wilson worked on a road construction crew and spent his final years in a mental institution. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2006.