The Cumberland County Board of Supervisors brought the locality one step closer to being home to a controversial landfill by approving a permit for the 1,200-acre facility, despite several residents speaking in opposition over a seven-year fight between economic and environmental impacts.

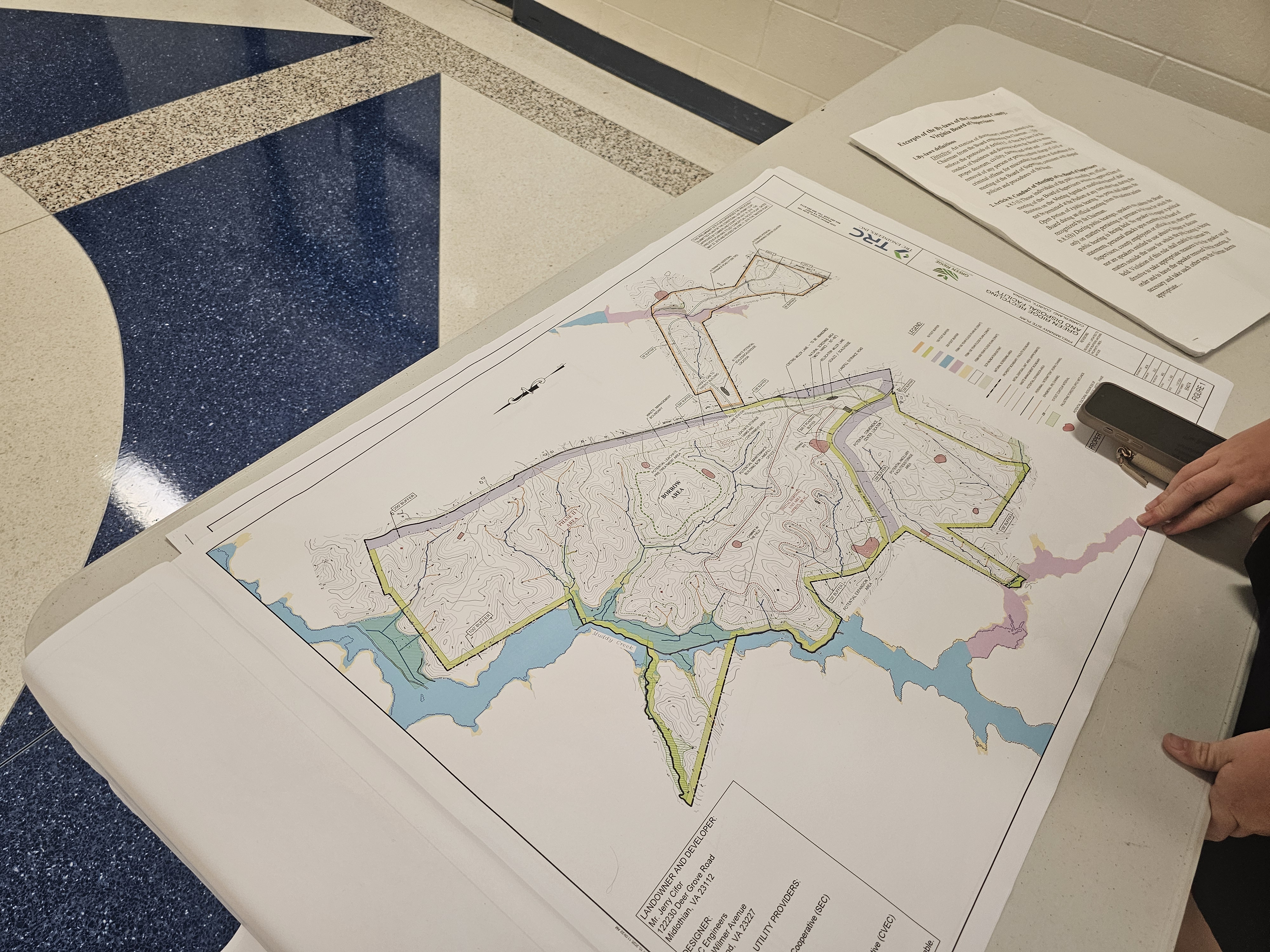

By a vote of 4-1, the supervisors this week approved a conditional-use permit for the Green Ridge Recycling and Disposal facility to accept trash for an initial 104-acre collection area, creating revenue for the rural county.

Residents voiced concerns over harms to groundwater wells, impacts on neighboring Black historic and cultural sites, damages to quality of life and a fear that the county is being steered down a path that will bring long-term harms.

“Cowards” and “You just voted for money” were among the chants of a few dozen crowd members after Monday night’s four-plus-hour public hearing. The project now moves on to a state permit approval process that is already underway.

The Green Ridge landfill project has drawn the ire of some residents since June 2018, when the county approved a conditional-use permit and host agreement for what was then proposed as a mega-landfill, meaning it would accept 5,000 tons of trash a day. Community opponents fought the project, and COVID-19 pandemic issues and problems in obtaining a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to mitigate harms to wetlands in the project area led to construction delays.

The original permit came with a deadline to begin constructing the facility within seven years, but that didn’t happen.

So the company, Canada-based GFL Environmental, resubmitted the permit application with a downsized footprint that eliminated the need for an Army Corps permit. The planning commission recommended that the board of supervisors deny the updated project.

The landfill will now be built in phases to ultimately achieve a 170-acre disposal area accepting up to 3,500 tons per day.

Concerns about historic site, environmental impacts

The project will no longer require a rerouting of Pine Grove Road, which runs up to the landfill near the Rosenwald-built Pine Grove School.

Constructed in 1917, the school was built by Julius Rosenwald to provide an education for Black students during the era of Jim Crow segregation. Since the inception of the landfill’s proposal, AMMD Pine Grove Project, a group working to preserve the school and turn it into a living museum and cultural center, has received a grant from the federal government to stabilize the school.

AMMD Pine Grove Project has pushed for a “tourism not trash” concept. The group organized a series of weekend protests leading up to the public hearing Monday.

“This is not about property,” Muriel Branch, the group’s founder, said at the meeting Monday night in the cafeteria of Cumberland County High School and Middle School. “This is about heritage. This is about justice. This is about legacy.”

Cale Jaffe, director of the Environmental Law and Community Engagement Clinic at the University of Virginia who has been representing AMMD Pine Grove Project pro bono, also raised concerns over the use of Pine Grove Road by an estimated 75 trucks a day, each carrying 20 tons of trash before a second entrance off Virginia 60 is built to accommodate a landfill expansion. Conditions in the permit dictate Green Ridge pay for repairs to any Pine Grove Road damage, Jaffe noted — an indication, he believes, that damage will happen.

Residents also expressed concerns about impacts on nearby Muddy Creek, which feeds into the James River. Continued criticism over the project stemmed from concerns over truck traffic, light pollution, odors, the visibility of the landfill and the potential for fires.

Betty Myers, founder of Cumberland County Landfill Alert, which has battled the proposal for years, brought a several-inch-thick stack of papers representing the few thousand petitioners against the project. She argued that the past conditional-use permit and host agreement weren’t in effect anymore, so the county wasn’t beholden to any decision.

“Why not just walk away?” said Myers.

Robert Bishop, who owns property in Cumberland, asked attendees who were against the project to raise their hands if they opposed the project, prompting a majority of people in the room to put their palms toward the sky.

“You look at these people,” Bishop said. “The citizens … [have] appeared.”

Mike Setaro, treasurer of CCLA, said that the permit might include enforcement protections, but that the company could dispute any issues arising from the landfill, which would lead to burdensome legal challenges.

Hiring an attorney to handle a case would be expensive, he said. “That’s going to cost us,” he said. “I can afford to do it, but it’s going to cost me big money to fight against the corporation.”

Landfill will come with environmental protections, company says

According to Green Ridge, the company will provide $1.7 million annually to the county through a combination of host fees, taxes, additional annual payments and savings the county would realize by not needing to spend about $1 million in its waste operations.

The company presented its plans to reduce environmental harm by using a material as a liner that expands when mixed with water to self-heal after being punctured. The landfill also will be limited as to the types of waste it will accept, and will feature a methane-capture technology to reduce odor while also converting the emissions to sellable natural gas as an additional revenue source for the company and county.

Hours of operation were reduced from the original 24 hours a day to 6 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays and 6 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Saturdays. Outside of those times, vehicles entering the landfill would need to be owned by the company, but project spokesperson Jay Smith said, “We will not be accepting any waste past 5 p.m. … even from GFL trucks.”

The company will pay a $125,000 salary for a landfill liaison hired by the county to monitor issues. Any harms to nearby residents could result in the company remediating a property to its prior condition, buying the property at 125% of its value or reaching an agreement with the property owner to resolve the issue.

Jerry Cifor, president and CEO of Green Ridge, said in an interview after the meeting, “It’s just been a long, difficult process.

“You can see why our landfills in this country are just getting older and older and older. You can’t get new ones permitted. It’s been a decade that I’ve been working on this,” Cifor said. Landfill issues come from design problems, he said. “In my 39 years in the industry, I’ve been exposed to hundreds of landfills, and very few of them have issues.”

Supervisor Jonathan Newman was the only board member to speak in favor of the project Monday night, with Chairwoman Eurika Tyree and supervisors Paul Stimpson III and Robert Saunders Jr. voting in support.

“We looked at this as many different ways as we possibly could,” Newman said, including consideration of environmental protections, the possibility of other landfills reducing in size and noting that 16 people would be employed by the landfill. “It’s not an easy process.”

Supervisor Bryan Hamlet was the lone “no” vote.

“I beseech my fellow board members up here to listen to the people that elected you to represent them,” Hamlet said.

Residents Cardinal News spoke to in the months leading up to Monday’s public hearing said language in the previously approved host agreement, called a frustration clause, forced board members to approve the project. Hamlet put the question to the attorney whom the county retained for the proposal.

“Is this board legally obligated to pass a new CUP?” Hamlet asked

“I would say no,” said attorney Scott Foster with Gentry Locke.

Hamlet also asked Green Ridge’s attorney, William Shewmake, to swear under oath before asking a series of questions, including whether a provision to not accept out-of-state trash could be skirted by delivering such trash to a transfer station in Virginia and then taking it to the Cumberland site. Hamlet also asked if the company had given money to supervisors regarding the project.

In response to the question about out-of-state trash, Shewmake said, “You’re asking me a hypothetical that doesn’t occur,” and deferred that oversight to the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. As for the question on buying votes, Shewmake added: “Green Ridge [or] its affiliates have never made financial contributions to the board in connection with this project.”

After the hearing, Hamlet said, “The body politic of Cumberland County, the board has spoken.

“You can’t really litigate because you didn’t like the outcome of a vote,” Hamlet said. “Unfortunately, I think, there’ll be a big changeover come the next election in Cumberland County. As you know, the original CUP and host agreement that was passed — nobody from that vote is currently on the board.”

Green Ridge has already received approval for the first part of its solid waste permit from the DEQ. A second approval is expected to have a series of state and federal agency reviews leading up to a final decision in January 2027.