Winsome Earle-Sears has changed campaign managers and changed her approach. After months of near silence, the Republican candidate for governor is now taking a higher profile — including an appearance last week on CNN that quickly turned contentious when the interviewer pressed her on whether she backs President Donald Trump’s downsizing of the federal government.

In 48 other states, that might be a softball question for a Republican. In the two states next to the nation’s capital — Maryland and Virginia — it’s not. Earle-Sears’ inability to come up with a good answer for why we shouldn’t care about job reductions to the biggest employer in the state’s biggest metro is just one of many problems that have plagued her campaign. A lack of money is another. The most recent campaign finance report showed that Democrat Abigail Spanberger has about five times as much money in the bank, some of which has now been used to turn Earle-Sears’ CNN interview into an ad for the Spanberger campaign in Northern Virginia. When your candidate’s interview gets turned into an ad for the other side, that’s never a good sign.

Polls consistently show Spanberger with a healthy lead, even if some of the double-digit figures reported do strain credulity. The underlying fundamentals in those polls, though, point to challenges that could confront any Republican candidate for governor in Virginia this year: Trump is deeply unpopular in the state, and Virginians have a history of electing a governor who is from the opposite party of whoever sits in the White House.

All that has led to chatter among Republicans: What are the prospects that Virginians will split their tickets this fall? More to the point: What are the odds that the incumbent attorney general, Jason Miyares, might survive even if Earle-Sears loses? I’ve heard Republican legislators talk about whether they can “save” Miyares. The Richmond Times-Dispatch addressed the question in a story over the weekend. At the weekly political briefing hosted by the pro-business group Virginia FREE, one of the topics last week was about the potential for ticket-splitting.

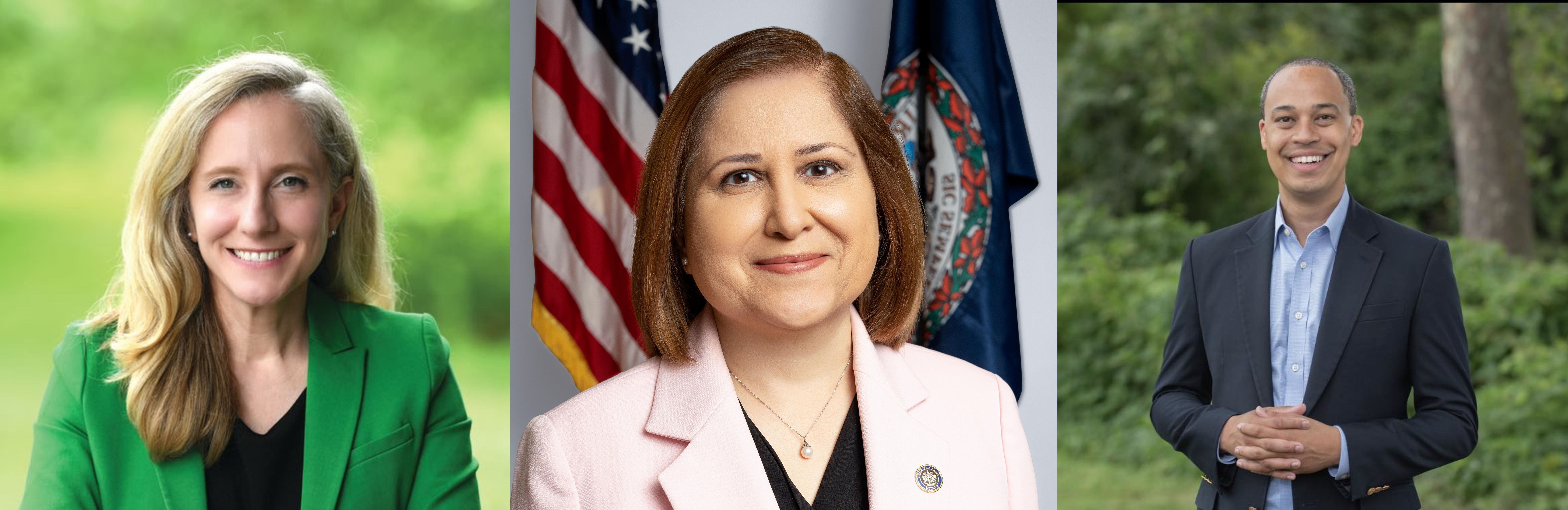

There are lots of ways that could happen. The two parties this year have put forward tickets we’ve never seen before. Neither party has nominated a straight non-Hispanic white man for office. Gender might be removed as a factor in the governor’s race since both parties have nominated women, but there’s always the possibility of some “undervote” — a small number of voters who vote in one race and simply don’t vote in another. There’s always some fall-off between the top of the ticket and down-ballot candidates, but could we see it the other way around this year? Will some male voters not register a choice for governor but check the box (or fill in the oval) for two of the three men on the ballot, Republicans John Reid for lieutenant governor and Jason Miyares for attorney general or Democrat Jay Jones for attorney general? Spanberger has had somewhat cool relations with some leading Black Democrats in Virginia; with Earle-Sears as an option for governor, how will that play out? Will some Black Democrats pass on Spanberger — and Ghazala Hashmi for lieutenant governor — but turn out for Jones for attorney general? Will some Republicans who are uneasy about a gay nominee not vote for Reid?

All these scenarios might involve a small number of voters, and in a blow-out, small numbers don’t matter. In a close election, they do. I cannot predict the future, but I can look to the past, so let’s see what history — especially recent history — tells us about the prospect of ticket-splitting.

Our modern political history in Virginia begins in 1969 with the election of Linwood Holton, the first Republican since the tumultuous times after the Civil War. It also began with a split-ticket election — Holton won, but his two running mates did not.

For the first 10 elections of that modern era — from 1969 to 2005 — ticket-splitting in Virginia was the rule, not the exception.

Six elections — 1969, 1973, 1977, 1993, 2001 and 2005 — produced split tickets.

The four exceptions were three Democratic sweeps in 1981, 1985 and 1989 and a Republican sweep in 1997.

For the past 20 years — or, in election terms, four elections — we’ve always had sweeps. Republican sweeps in 2009 and 2021, Democratic sweeps in 2013 and 2017.

So what does that mean? Does this mean we have moved irrevocably into an era of sweeps? Or have these past four elections simply been an aberration like the 1980s were?

If we look nationally, the answer is clear: Ticket-splitting is on the decline.

It does happen, though, just not as often as it once did. In 2024, four states voted for Trump for president but elected Democratic senators: Arizona, Michigan, Nevada and Wisconsin. On the other hand, political analysts found that ticket-splitting in 2024 showed an uptick — mostly in the form of Trump outperforming other Republican candidates, which allowed some Democrats to win. The website Campaign Now discusses the numbers more deeply. As with anything involving Trump, it’s hard to tell how much of that ticket-splitting was a Trump-inspired factor that is specific to him and how much is more systematic.

In any case, Trump’s not on the ballot in Virginia this year, as much as some Democrats wish he were (and are trying to put him on the ballot in a figurative sense).

Let’s look at some numbers. Specifically, let’s look at the variance between each party’s best-performing candidate and worst-performing candidate over the years. In the ticket-splitting of the 1970s and even the 1990s, we saw some big differences.

In 1973, Republican Mills Godwin won the governorship with just 50.7% of the vote, while the Republican candidate for lieutenant governor (John Dalton) took 54.0% but the Republican candidate for attorney general (Pat Echols) took just 29.4%. Echols had the misfortune of running against a popular Democratic incumbent (Andrew Miller), but Godwin clearly had no coattails for him. That was a 21.3 percentage point difference between the winning gubernatorial nominee and the party’s losing attorney general nominee.

In 1993, Republican George Allen led the ticket with 58.3% of the vote, and the Republican candidate for attorney general (Jim Gilmore) took 56.1% but the party’s candidate for lieutenant governor (Mike Farris) lost with 45.5% of the vote. That was a gap of 12.8 percentage points between the winning gubernatorial nominee and the party’s losing candidate for lieutenant governor.

Even in 1997, when Gilmore led a Republican sweep, there was a noticeable gap between his 55.8% winning percentage and the 50.2% that John Hager won in the lieutenant governor’s race.

In 2001, Democrat Mark Warner won the governorship with 52.2%, but Don McEachin, the party’s candidate for attorney general, lost with 39.9%. That’s a difference of 12.3 percentage points.

From 2009 onwards, though, we’ve seen far less ticket-splitting. 2009 Governor Lieutenant governor Attorney General Biggest difference from governor McDonnell 58.6 % Bolling 56.5% Cuccinelli 57.5% 2.1 2013 Governor Lieutenant governor Attorney General Biggest difference from governor McAuliffe 47.7% Northam 55.1% Herring 49.9% Complicated; see below 2017 Governor Lieutenant governor Attorney General Biggest difference from governor Northam 53.9% Fairfax 52.7% Herring 53.3% 0.6 2021 Governor Lieutenant governor Attorney General Biggest difference from governor Youngkin 50.6% Earle-Sears 50.7% Miyares 50.4% 0.2

About that 2013 race I listed as “complicated”: Ralph Northam in 2013 ran well ahead of his ticketmates, but that’s likely because Republicans nominated an extraordinarily weak candidate for lieutenant governor: E.W. Jackson. Had Republicans nominated a more conventional candidate, it seems likely the result would have been in line with the other two races. Terry McAuliffe won with a plurality because a third-party candidate peeled off some votes; there were enough write-ins for attorney general to pull Mark Herring below the 50% threshold, too.

In general, what we see is that all these percentages are tightening up, as voters opt for more straight-ticket voting.

In the military, they say amateurs talk strategy, professionals talk logistics. Likewise, in politics, amateurs talk percentages, professionals talk actual turnout, so let’s go pro. I’m going to set aside those 2013 results for the reasons above and look at the other three recent elections to see what the actual vote totals looked like, and what the falloff was from the top of the ticket. 2013 candidate Vote Falloff from governor’s race McDonnell 1,163,651 —– Bolling 1,106,793 -56,858 Cuccinelli 1,124,137 -39,514 2017 candidate Vote Falloff from governor’s race Northam 1,408,818 —– Fairfax 1,368,412 -40,406 Herring 1,385,390 -23,428 2021 candidate Vote Falloff from governor’s race Youngkin 1,663,158 —– Earle-Sears 1,658,332 – 4,826 Miyares 1,647,100 -16,058

What we see is that over the years, even though we have more people voting, the voter falloff is dropping. This might reflect declining split-ticket voting (even though all these elections resulted in sweeps), but more likely reflects more straight-ticket voting. Once voters start marking candidates, either Democrat or Republican, they just keep going, whereas in the past, they might have stopped.

If you buy the argument that Miyares has the best chance to win — and I realize Republicans, publicly at least, will want to dispute that any of their candidates might lose — this is the electoral challenge he faces. He can’t afford any voter falloff from the top of the ticket. On the contrary, he needs to gain votes and outrun his party’s candidate for governor. Northam did that in the 2013 race, but his opponent was weak. Jones may not be. Under some scenarios — Black voters hesitant about Spanberger but not about Jones — Jones might conceivably be stronger than the top of his ticket. On the other hand, Miyares is the only incumbent on the statewide ballot. That might help — although it didn’t help his predecessor, Mark Herring, four years ago.

This is where any crystal ball looks more like a bowling ball. For the sake of this argument, let’s assume that Spanberger wins the governorship. What will her winning percentage/vote total be? Knowing that would help us calculate how many extra votes Miyares would need to stand up to a potential Democratic sweep. (Or Reid, for that matter.)

Here’s what we do know: Four years ago, Miyares won by 26,536 votes. Put another way, for Democrat Mark Herring to have won, he’d have needed 26,537 more votes than he got. Was that possible? That’s hard to say. Herring outran the rest of the Democratic ticket. The best way for him to have generated more Democratic voters would have been to increase Democratic turnout (which was essentially flat, compared to 2017, in many Democratic-voting localities). It’s hard, though, for the candidate at the bottom of the ticket to motivate reluctant voters if the top of the ticket hasn’t. There’s a reason why gubernatorial candidates are often called standard-bearers. They are supposed to lead the way.

By contrast, for Republican Jill Vogel to have won the 2017 lieutenant governor’s race, she’d have needed 143,893 extra votes. For Republican John Adams to have won the attorney general’s race that year, he’d have needed 175,851 extra votes.

The vote totals this year are hard to predict — that depends entirely on what level of turnout we have, and how that turnout is distributed around the state. Four years ago, we saw high turnout, and turnout was elevated in the most Republican parts of the state, meaning rural Virginia, especially Southwest Virginia. That turnout was still often low compared to elsewhere, but it was significantly higher than in the past. For any Republican to win in Virginia, in any year, they need two things: to hold down Democratic margins in Northern Virginia and to turn out as many Republicans as possible in Southwest Virginia. (That’s why Earle-Sears’ dismissal of the jobs concern in Northern Virginia is so frustrating; that just feeds the potential for an even bigger Democratic rout there than usual.)

Percentages are easy to work with, even though that means reverting to amateur status. With the exception of Bob McDonnell’s 58.6% winning percentage in 2009, no candidate for governor in this century has won with more than 53.5% of the vote. In the modern era, the largest Democratic percentage for governor is 55.2% — and that was 40 years ago, with Gerald Baliles in 1985.

The double-digit leads Spanberger has in public polls are from polls of registered voters, not likely voters. That’s a vital distinction. While we don’t know yet who will actually show up to vote, there’s a decent chance that her “true” lead is smaller. Neither Democrats nor Republicans should assume we’re headed for a double-digit blowout. However, it does appear the political ground this year favors Democrats. Republicans need a way to defy that — and if any down-ballot candidate hopes to win if their standard-bearer can’t, they need to find a way to win votes she can’t. The numbers above show how many that might be.

Who’s on the ballot this year? We can tell you.

We’ve now updated our Voter Guide with pages for each county and city in Virginia, where you can look up who’s on your ballot this fall.

Want more politics? Sign up for West of the Capital, our weekly political newsletter that goes out each Friday.