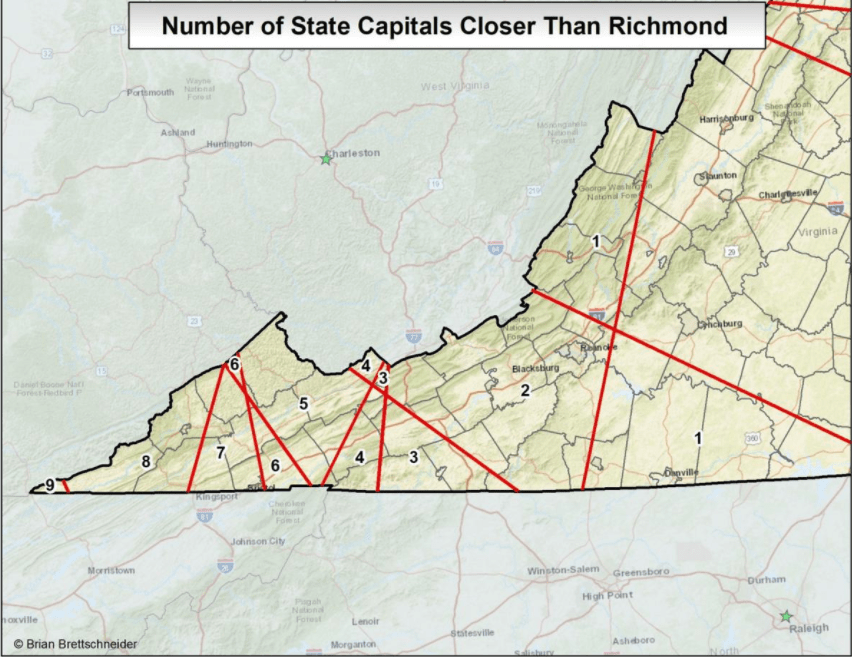

My favorite map of Virginia is this one. It’s from a computer program set up by Brian Brettschneider, a mapping hobbyist in Alaska.

By day, he’s a climatologist with the International Arctic Research Center in Fairbanks, a job that entails making a lot of weather maps. On the side, he makes other maps for fun. About seven years ago, he created a program to determine which parts of which states were closer to state capitals other than their own.

Alaska and Hawaii, our two noncontiguous states, are the only ones that don’t make the list. You can be at Cape Wrangell on Attu Island in the Aleutians, the westernmost point of Alaska, and still be closer to the capital of Juneau than any other.

All the other 48 states have at least some part of their territory that’s closer to somebody else’s state capital than their own. Often it’s just a small slice of territory, sometimes it’s more. Either way, there’s typically a part of every state that’s closer to one or two or maybe three state capitals.

And then there’s Virginia.

Two states — New York and North Carolina — have some slice of territory that’s closer to seven other state capitals than it is to Albany or Raleigh.

Virginia has some places that are closer to eight other state capitals. And then a smidge in the corner of Lee County that’s closer to nine other state capitals.

For some, this geography is trivia. For those who live in Southwest Virginia, it’s simply a part of life anytime their life intersects with the state government in far-off Richmond. For Winsome Earle-Sears, the Republican candidate for governor, this is a campaign platform.

When Earle-Sears and her Democratic counterpart, Abigail Spanberger, were confirmed as the nominees of their respective parties in early April, I contacted her campaign to request an interview on policy — specifically energy policy, since it’s clear that energy issues are going to dominate the coming years. My interview with Spanberger published in late April. It’s taken until July to get an interview with Earle-Sears, and later this week, I’ll have a column devoted to her views on energy. However, in the course of our interview, Earle-Sears also addressed an unusual campaign proposal she has related to Virginia’s unique geography above.

She wants to put a regional governor’s office in Southwest Virginia.

She’s talked this up in social media posts, and I was curious if she had any details about what she envisions. Here’s what Earle-Sears told me in an extended interview (the rest of which will appear in a future column): “One of the things I heard as we were campaigning in the Southwest [in her 2021 campaign for lieutenant governor] is that we vote for you but after the election we never see you again,” she said. “I promised myself that they’d never say that about me.”

People who live farther southwest than I (I’m just north of Roanoke in Botetourt County) are in a better position to judge whether she’s kept that promise or not, but that’s not the subject here. Earle-Sears said that whenever she’s been in Southwest Virginia, she’s reminded by people how they’re closer to other state capitals than they are to Richmond. “I thought to myself, yeah, I’m here now, but how will they really know we care? How can we put a stop to them thinking we don’t care?”

That’s when she hit upon the idea of a permanent office. “What if we put a governor’s office somewhere in the Southwest, somewhere central, not too far, but past Abingdon somewhere, close to the mountains. What if we put a governor’s office there and it’s a working office and I’ll be there from time to time and maybe we move a secretariat [to be based there]. I think I have to get the approval from the legislature, but one that’s close to the industry there, and then they’ll always know that a governor’s office is nearby. Yes, we can use technology now but I think a presence means something — and it’s a stately type of office, so they understand, OK, Richmond cares about us. The governor sees us. And I daresay the next governor after me and any governor — they would find themselves probably being ripped at any suggestion that they close that office.”

Earle-Sears is definitely right about the latter; I could write an indignant column about any attempt to close that western governor’s office in my sleep. First, though, we need to establish one.

I cannot find any examples of any other states that have something similar to what Earle-Sears is proposing — although, as we just saw, no other state has the geographical imbalance that Virginia does.

There are some states that have multiple residences for their governor. The most notable — and the most relevant for us — is North Carolina. In 1964, the Asheville Chamber of Commerce donated a fancy house to the state to serve as the official “western residence” of the governor — and to make sure North Carolina’s chief executive spent more time in the western part of the state. It’s unclear how well that has served its purpose. The state’s own website, in its description of the Governor’s Western Residence, says that “many locals don’t even know it’s there” and that “the governor and his family visits occasionally.” Still, it’s there and does get used when the governor is in the area. In 2014, then-Gov. Pat McCrory was in residence when one of his constituents wandered across the grounds, prompting security to warn that the governor stay back from the scene. I should probably mention that the trespassing constituent was a bear.

However, Earle-Sears isn’t talking about a residence; she’s talking about a working office.

There are several ways to evaluate this.

We can look at this as a political ploy: To win statewide, any Republican needs a big turnout from Southwest Virginia, so this is an easy thing to promise.

We can ask rhetorically whether Southwest Virginians feel close to Sen. Mark Warner and Tim Kaine simply because they have regional offices in Abingdon and Roanoke.

Or, we can take this seriously. I’m assuming Earle-Sears is serious about her proposal, so I’m inclined to treat it that way, as well. She’s proposing something different than the regional offices senators and U.S. House members have — those are essentially constituent service offices. What would elevate Earle-Sears’ idea beyond that is if she, as governor, really did spend time there working — not as a photo op sort of thing but just as a matter of routine business.

The first example that comes to mind is how the British monarch, each year, decamps to Scotland, partly to emphasize that the king (or queen) takes Scotland’s national identity seriously. Of course, that comparison would work better if the prime minister worked part-time in Edinburgh, but the PM doesn’t, so let’s move on.

There is another precedent to cite, though, and it’s a good one because it’s from Virginia. The constitution that Virginia adopted in 1870 required the state’s Supreme Court to meet annually in Staunton, Winchester and Wytheville. The 1902 constitution stripped out the three names and simply authorized the court to meet at “two or more places.” Those two became Richmond and Staunton. The drafters of the 1971 constitution — the one we presently have — removed that provision as unnecessary. There’s nothing to stop the Supreme Court from deciding it could meet around the state; it just doesn’t. The last constitutionally mandated session in Staunton was in 1970.

The reasons for designating Staunton, Winchester and Wytheville in that Reconstruction-era constitution are lost to history but likely have to do with practicality: Lawyers didn’t want to have to saddle up a horse — or ride the iron horse — to Richmond.

Highways, both the asphalt kind and the information kind, have changed our concept and necessity of travel, but what if Earle-Sears is onto something here? The next governor — be it Earle-Sears or Spanberger — could establish a custom of working out of some western community for, oh, let’s say, the month of August. The legislature could even pass a constitutional amendment and send to voters a referendum on whether to require such a residency. I don’t expect either of those things to happen, but the point is they could — and the former could happen right away, if a governor wanted it to.

Of course, working somewhere doesn’t automatically mean a governor is suddenly in touch with the community. I once wrote a story for Cardinal while on a layover between flights in the Philadelphia airport, but that stay didn’t necessarily give me any insight into the problems confronting southeastern Pennsylvania, other than the high prices for a Philly cheesesteak. Still, it’s a symbolic gesture, one that could be made concrete. We’re closer to making that happen than you might think.

Earle-Sears says such an office should be “past Abingdon” and “stately.” We have such a building available: the former C. Bascom Slemp Federal Building in Big Stone Gap, where federal courts once met but no longer do. It’s hard to imagine anything more stately than this 1913-era building, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. I’ve been making the case that statewide candidates should visit Southwest Virginia (especially Lee County, our westernmost county) just to show they’re making an effort to understand all parts of the state. This might be a more substantive way to do that: Declare that they’re willing to work a certain number of days per year out of a western office. We have the place; they just need to make the promise.

See where the candidates stand in our Voter Guide

Both candidates for governor have answered our questionnaire. Find their responses in our Voter Guide. We also now have listings for every city and county in Virginia, where you can see who’s on your local ballot. Early voting begins Sept. 19.

Want more politics? Sign up for West of the Capital, our weekly political newsletter: