The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

If you’re a Virginian, there’s a good chance you live in a burned county.

That’s the informal term many historians and researchers use to describe the nearly half of Virginia counties (and a handful of cities) that suffered significant losses of official records at some point in the past two-and-a-half centuries or so.

The physical records kept at county courthouses — deeds, wills and marriage records, to name a few — permanently illuminate the past and provide a critical link to our ancestors as time inevitably erases human memory. As the retelling of our history becomes more inclusive, and we acknowledge that a broad swath of Americans played a role in who we’ve become today, these records are a permanent wellspring of their stories.

One of those remarkable tales involves the salvation of county records so complete that they’ve been recognized by the Virginia House of Delegates. In 1781, when war came to Southside Virginia, quick thinking by Elizabeth Bennett Young, the wife of an Isle of Wight County deputy clerk, saved the records of one of the first Colonial jurisdictions. More than eight decades later, when Civil War cleaved the country, another local — Randall Booth, an enslaved man — repeated Young’s feat, ensuring the survival of a long chain of documentation that tells of the earliest days of the modern American nation.

Throughout Virginia’s history, county courthouses have been something of a magnet for trouble. Particularly in the American Revolution, British forces targeted county courthouses because striking them was a one-two punch, destroying the legal documents Patriots and their sympathizers needed to carry on day-to-day affairs, and hitting a symbolic center of administrative power.

In a daring June 1781 raid, the hot-headed 27-year-old Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton led 250 British troopers to Charlottesville in an effort to capture members of the Virginia General Assembly who had convened there. While most of the assemblymen were able to evade capture, the Brits ransacked the town, destroying weapons caches and burning legal records on the courthouse green.

During the Civil War, Union soldiers sought out county courthouses for the same reason, and there were more of them to target. Records from Rockingham, Washington and Lee counties were among those destroyed by match-happy Yankees. A handful of hapless county clerks, in Hanover and James City counties for instance, sent records to Richmond for safekeeping, only to have them burned when the Confederate capital went up in flames in 1865.

Sometimes fires had no connection to war. Buchanan County’s courthouse burned in 1885. Then a flood destroyed its records again in 1977. In fact, catastrophic weather, pests, theft and vandalism have all contributed to records’ demise, often rendering “burned county” a misnomer. The Library of Virginia maintains a database of jurisdictions whose records have been destroyed. Even Isle of Wight County is on this list because some of its earliest records — the county was founded in 1634 — have gone missing, although some of its surviving records date to the 17th century.

Without the daring actions of Young and Booth, however, Isle of Wight’s records would undoubtedly have ended up woefully incomplete like the counties around it, taking from generations of researchers an irreplaceable asset.

Elizabeth Bennett married Francis Young in Brunswick County around 1750. When Bennett’s father died, she inherited roughly 1,000 acres in Isle of Wight about five miles south of what was then the county seat, Smithfield. It was there in 1768 that the Youngs built Oak Level, their plantation home.

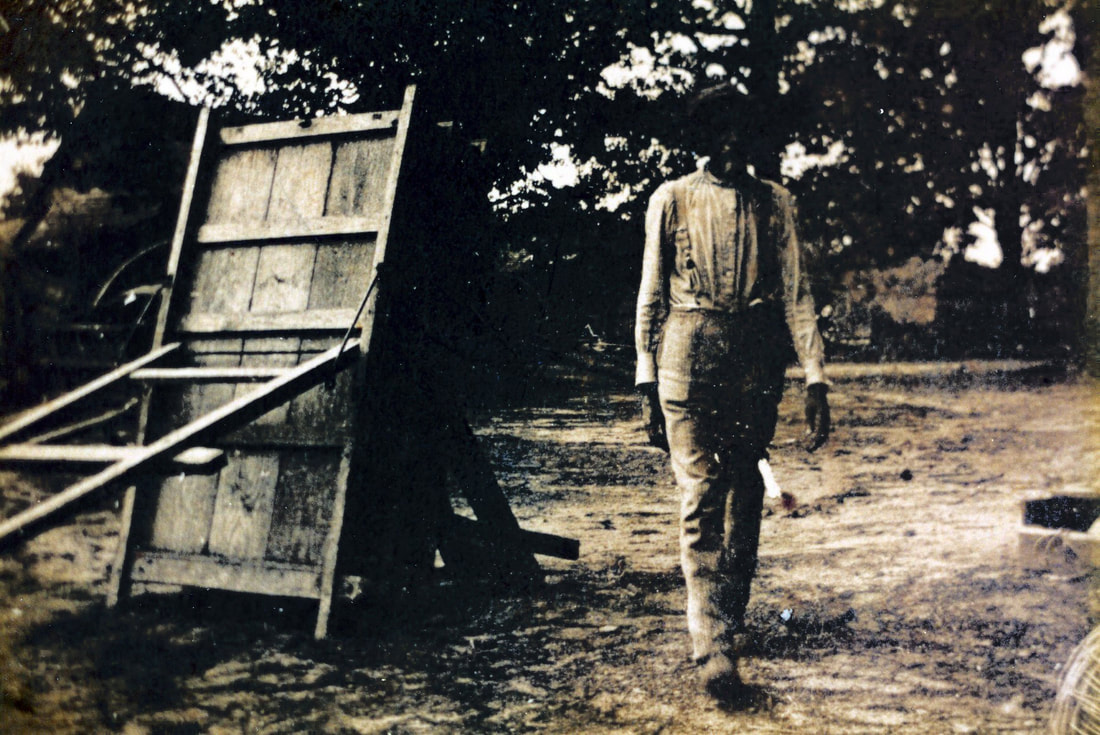

Isle of Wight sits on Virginia’s coastal plain where the James River empties into Hampton Roads. Much of the county is tranquil, away from the bustling cities of Tidewater, and the terrain is broad and level, with fertile fields stretching to distant tree lines. This is the vista the Youngs would have seen from Oak Level, which still stands today.

“My favorite part is how quiet it still is,” said Parker Mathias, whose grandparents spent decades restoring the home, which he and family members now operate as Oak Level Acres, a wedding venue and short-term rental.

Mathias said the home retains notable 18th-century features, such as its richly hued wood flooring. And he is proud to have a distinct link to the nation’s defining conflict. “This is not just an old home,” he said. “There’s a connection to our history.”

Francis Young was appointed deputy clerk of Isle of Wight in 1768 but stepped away from the role to serve in the Continental Army for two years early in the war. As a prominent farmer, he would have been part of the local militia even after he resumed his duties as deputy clerk. When word came in July 1781 that Tarleton, then carrying out orders to destroy Patriot assets throughout Southside Virginia, had his sights set on Smithfield, Young would likely have been a part of any resistance that locals were fit to muster.

Tarleton’s reputation preceded him. Among many Americans he was renowned for his brutality at the Battle of Waxhaws in South Carolina, when the British soldiers under his command overwhelmed Patriot forces and purportedly killed those trying to surrender.

While Francis Young and other local able-bodied males were preparing for the imminent arrival of trouble, Elizabeth sprang into action. She gathered the county records, put them in a trunk and spirited them away.

Where, exactly, she took them is unclear. Some oral tradition suggests she hid them at Oak Level. One local historian claimed she fled with them in the opposite direction. Whatever the case, one thing is clear: she buried the trunk containing the records so the British, or their informants, wouldn’t stumble across them. Tarleton continued to Portsmouth, and Isle of Wight’s precious records remained safe, returning to their rightful place after the war.

“The story of Elizabeth fits in well with the rest of the history of Isle of Wight,” said Jennifer England, director of the Isle of Wight County Museum.

Often people associate peanuts and ham with Isle of Wight and Smithfield, and for good reason; the area is a major producer of both. (The Isle of Wight County Museum displays both the world’s oldest peanut from 1890 and the world’s oldest ham from 1902.)

But England says Isle of Wight should also be known for its significant Colonial history. “I like to tell everyone there is more to Virginia than the Historic Triangle,” she said. “Early on there was settlement that spread across the James River. It’s really more of a historic square.”

The records that Young saved burnish those historic credentials, according to England. In 2014, the House of Delegates passed a resolution commemorating the life and legacy of Young. “Elizabeth Young’s quick thinking and decisive action protected what are some of the oldest and most complete court records in the United States that today provide historians, genealogists, and the general public with valuable information,” the resolution read.

What’s even more remarkable, according to England, is that the county’s records were saved twice. Isle of Wight, located along the strategically important James River, saw action during the Civil War, but unlike in so many other Virginia jurisdictions, the records never became a casualty.

Randall Booth was a man who was enslaved on the plantation of Nathaniel Young, the county’s clerk of court at the time and a descendant of Francis and Elizabeth Young. In 1862, with Union gunboats patrolling the river, Booth took the county records first to Greensville County, then to Brunswick County, where they remained for the duration of the war.

For his efforts, Booth earned the enduring gratitude of prominent local citizens and was bestowed the prominent position of caretaker of the courthouse. Today, at the Isle of Wight County Courthouse Complex, the Randall Booth Records Room is named in his honor.

Many days, you can find archivist and conservator Valerie Schmidt-Wilson there. She has been working for 13 years to preserve and protect Isle of Wight’s records. Schmidt-Wilson said that there are hundreds and hundreds of unique and enlightening records available for researchers in the county, and that it’s not accurate just to think of these as old, dusty scribblings.

“Try to tell your kids about names and dates, and they’ll plug their ears,” she said. “I probably would too.”

Instead, what the records reveal, according to Schmidt-Wilson, are absorbing and nuanced stories of real people navigating a complicated world. Peeking through the records are everyday dramas and extraordinary episodes. There’s a coroner’s inquest from the early 18th century for a man who killed his entire family. In June, Schmidt-Wilson gave a presentation about Timothy Tynes, who freed his slaves and was sued by his extended family for such an audacious deed. There are countless other true stories in Isle of Wight’s records waiting to be discovered, Schmidt-Wilson said.

England, of the Isle of Wight County Museum, said that it’s not just Isle of Wight and Smithfield residents who owe Young and Booth a debt of gratitude. They helped preserve the early history of the American nation. Their courageous acts permanently saved a chronicle that in so many other places proved vulnerable to the unpredictable whims of history. That it happened locally is a great source of pride, according to England.

“That’s a huge gem in the crown of Isle of Wight,” she said.