The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

It’s easy to confuse Dr. William Fleming, military officer and physician, with other Revolutionary-era Williams — William Christian, William Preston, and a different William Fleming who was a judge and delegate to Continental Congress.

In Roanoke, a high school bears his name, but otherwise he is little remembered. It’s a fate not befitting a man who served as acting governor during arguably the worst crisis of Virginia’s Revolutionary era, and who carried a lead musket ball in his chest from Oct. 10, 1774 — date of the Battle of Point Pleasant — to the day he died.

William Fleming spoke with a Scots accent, as did many on the Virginia frontier. He was born in Scotland in 1728, the third son of Leonard and Dorothea Fleming. Around age 16, he decided to study medicine. By 1751, he was in Nansemond County, Virginia, where he may have followed family friends.

In 1755, Fleming was commissioned into Virginia’s provincial forces and ordered to Fort Dinwiddie, in present-day Bath County west of Warm Springs. The trip to Fort Dinwiddie took him through the valleys of the Calfpasture and Cowpasture Rivers, the first of many journeys through the scenic Virginia backcountry.

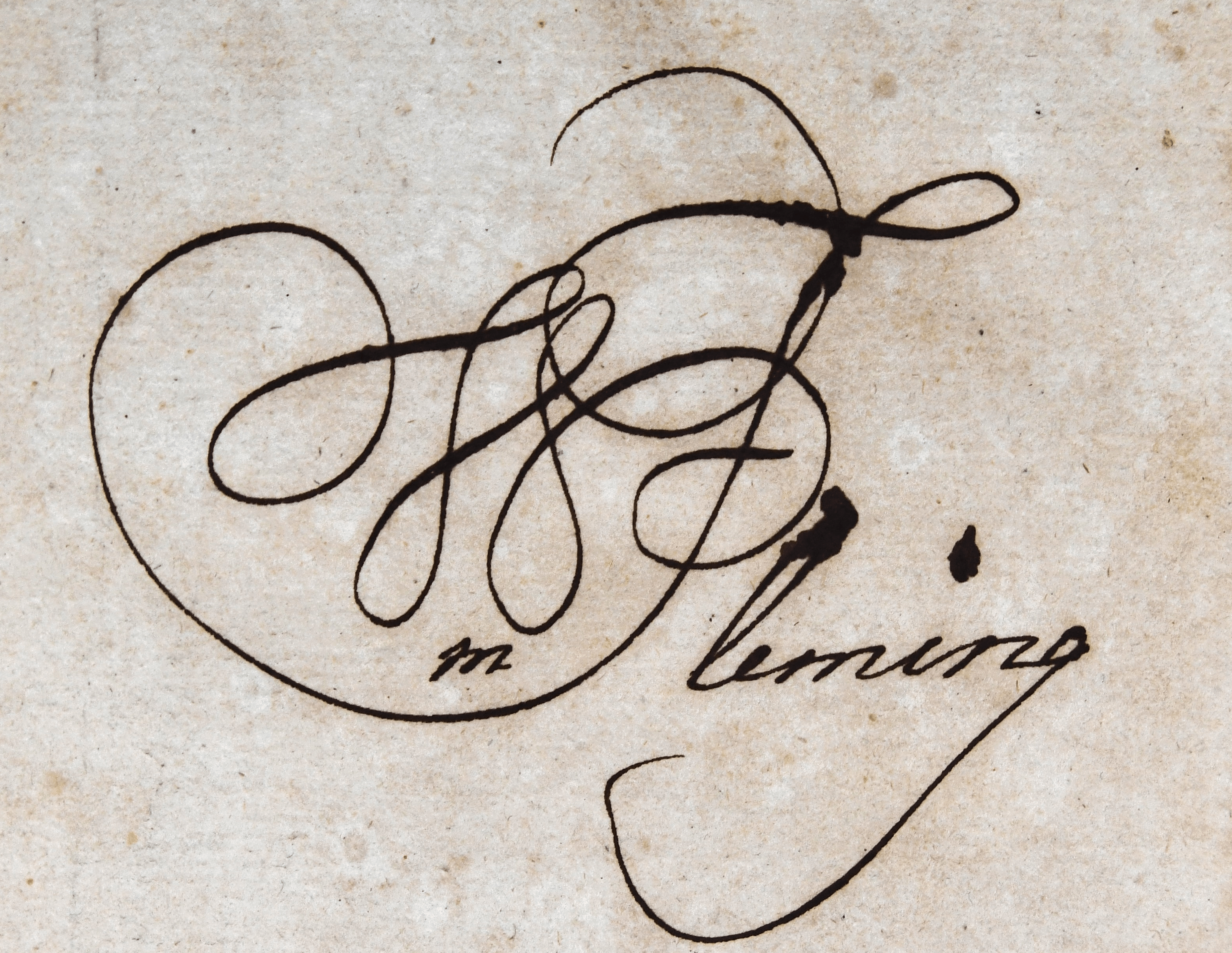

No portrait exists of Fleming. He was described as being of medium height, with blue eyes, brown hair, and a Roman (or eagle-like) nose scarred by a saber. He kept all or most of his teeth and was clean-shaven. He had a pleasant manner. As a Virginia gentleman, he enjoyed sports, socializing, a good dinner and the attention of ladies.

Fleming accompanied the ill-fated Sandy Creek Expedition in 1756, against the Shawnee on the Ohio River, with two men who became lifelong friends, William Preston, later of Smithfield Plantation in Montgomery County, and Andrew Lewis, later of present-day Salem.

In the next few years Fleming crossed and recrossed the mountains to postings in present-day Wythe and Smyth counties. His duties were not just medical. He owned books on military discipline and sketched out a parade-ground military formation — of dubious value when fighting Indians in thick forest.

By 1762, Fleming had decided to abandon a military career. He settled in Staunton, started a medical practice, and began courting Nancy Christian, daughter of merchant Israel Christian. At 19, she was almost an old maid by the standards of the day. He was 35. They were probably married at Israel Christian’s home by a Church of England minister. The Flemings and Christians were Presbyterians, but only Anglican ministers could perform weddings. Many Scotsmen belonged to both Presbyterian and Anglican congregations.

Nancy Christian probably brought at least one enslaved person to the marriage. When Nancy’s brother William Christian married, his father gave him seven enslaved people.

Nancy gave birth to a son, Leonard, in 1764. He was the only child to survive childhood until his sister, Elizabeth, 11 years later. Fleming’s medical skill could not save the six or seven babies who were born dead or died as infants. Six surviving children were born after 1775.

In 1765, a white mob murdered a party of Cherokees traveling through Augusta. Andrew Lewis tried to bring the culprits to justice, imprisoning one. Vigilantes broke down the prison door and freed him. Styling themselves “The Augusta Boys,” the vigilantes issued a £1,000 reward for the “capture” of Lewis and a £500 reward for Fleming.

Finding things too hot in Staunton, both Lewis and Fleming made plans to move to the Roanoke Valley. Fleming’s father-in-law, Israel Christian, was already living on Tinker Creek near Tinker Mountain.

Around 1767, the Flemings moved to 500 acres given to Nancy by her father. Fleming started building a house on Tinker Creek he called Bell Mount, later Bellmont or Belmont. A frame structure with clapboard siding, dormer windows and brick chimneys, it may have resembled Preston’s Smithfield. Fleming bartered medical treatment for labor and supplies, trading his neighbor John Robinson a bloodletting, a leg dressing, and “vomits” for work on outbuildings and a fence. Outbuildings included a shop, kitchen, smokehouse and “little house.” By 1772, the interior was finished with wainscoting, paneling and molding.

Fleming settled into life of a gentleman farmer and doctor. He made house calls on horseback. He traveled 84 miles to Staunton to operate on the breast of Mrs. James Hill of Staunton.

Although the Roanoke Valley was near the frontier, Fleming, Andrew Lewis and their friends were far from rustics. They modeled their social life on the tobacco grandees of Tidewater. Their children were taught by tutors, dancing masters and music maestros. They wore silks and satin when socializing, ordered books, and owned fine furniture. As in the East, their lifestyle was made possible by the forced labor of enslaved people, and they also employed indentured white servants. Family ties bound them to the East; Nancy Fleming’s brother William Christian married Patrick Henry’s sister Annie. The Westerners traveled to Williamsburg and other eastern destinations for politics, business and family affairs.

Land was wealth in 18th-century America, and the white population had an unquenchable appetite for it. Not long after the Proclamation Line of 1763 supposedly settled the issue, native people were already clashing with surveyors and settlers in the Ohio country. In 1774, Lord Dunmore, Virginia’s last royal governor, launched a war against the Shawnee and Mingo. Dunmore ordered Andrew Lewis to take a column north to the Ohio. Fleming received a colonel’s commission.

October 10, 1774, was the watershed in the life of William Fleming. He was 47. His life was one thing before, and something else after.

Early in the morning, two hunters from Lewis’s camp stumbled on the Shawnees. One hunter was killed but the other managed to alert Lewis. The Virginians advanced in columns. Fleming led the left.

About three-fourths of a mile from camp, the Shawnee attacked. Fleming took two balls through the left wrist but continued to command “with coolness and presence of mind,” according to an officer under him, “calling loudly to his men: “Don’t lose an inch of ground!” Shot again, three inches below the left nipple, Fleming was carried off the field. A piece of his lung as long as a finger stuck out of his chest. One of his attendants pushed it back in.

The three-week journey home was an agony of fever, swelling, oozing wounds and shooting pains in the hands and fingers, plus the 18th-century “remedy” of bleeding. Bullets had shattered both bones of the left forearm, and the little and ring fingers of his left hand were never usable again. The bullet remained in his chest for life.

He recovered enough to resume government duties. While in the Kentucky country attempting to sort out land claims in 1779, he dreamed that Nancy drowned. Unable to shake the nightmare, he wrote her: “I am frequently with you, sometimes relieving you from distressing Scenes, such as I hope in God you are not in….I hope after this business is finished, we will be no more separated, at least for any time.”

In 1780, he was elected to the State Council, which advised the governor.

In 1781, Virginia faced invasion by the British. In May, the General Assembly, Council and Gov. Thomas Jefferson decided to move the government from Richmond to Charlottesville. Fleming reached the town in Albemarle County by May 30.

British Gen. Cornwallis dispatched Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton to capture the rebels. The author of the Declaration of Independence was at Monticello. On June 4, just minutes ahead of the British, Jefferson escaped, or, as Tarleton phrased it, “provided for his personal liberty by a precipitate retreat.” Seven legislators, including Daniel Boone, were captured; the rest skedaddled over the Blue Ridge to Staunton.

![State historic marker for Dr. William Fleming in Staunton. Contrary to the text, William Fleming of Staunton and Roanoke was not a delegate to Continental Congress--that was a different William Fleming. Cardinal News emailed Jennifer Loux, the state's Highway Marker Program Manager, about the error. Matt Gottlieb, Highway Marker Program Research Assistant, responded: "Thanks so much for [the] catch!...I added a correction to our database and will alert Jen Loux about the error. She will enter the sign onto our replacement list. Repeated names cause all kinds of confusion in Virginia history, but it still stings when we learn about these sorts of errors. Thank you again for the note. With nearly 2,700 markers, we rely on the public for all kinds of help." Photo by J.J. Prats, Historical Marker Database.](https://cdn.statically.io/img/i0.wp.com/cardinalnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/6-Fleming-marker-in-Staunton.jpg?resize=780%2C585&ssl=1)

Jefferson’s term had expired on June 2. Amid the uproar, the General Assembly had failed to elect a successor. As the only Council member present in Staunton, Fleming became acting governor. He issued instructions concerning prisoners and the militia, and the assembly retroactively approved his actions. An official state website, commonwealth.virginia.gov, lists Fleming as “member of the Council of State acting as Governor,” June 4-12, 1781. The assembly elected a new governor, Thomas Nelson, on June 12.

Fleming’s last council meeting was June 26 in Staunton. In September, he sent his resignation to Gov. Nelson, citing his useless left arm and rheumatism afflicting his right arm. Family papers say he was more or less an invalid from Point Pleasant until his death. When he rode on horseback, the ball moved around in his chest, causing “something like torture.” And yet he traveled from Belmont to Kentucky and Richmond, unwilling to give in.

In 1782-83, he served on a commission to sort out financial affairs in Kentucky. When he reported back to Richmond, he took a load of crystals, fossils, bones and shells from the West. He may have joined Virginia’s pioneer scientific society, the Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, founded in 1773. The intellectual stimulation of “natural philosophy” may have distracted him from the pain.

At Belmont in 1787 were Nancy, Nancy’s mother, and five children age 3 to 12. The Flemings’ life of privilege was enabled by the forced labor of enslaved people.

In March 1788, Fleming was elected as one of Botetourt County’s representatives to the state convention on ratification of the Constitution. He was a strong supporter. On June 25, the convention voted 89 to 79 in favor. Patrick Henry, Nancy’s kinsman by marriage, opposed it.

In 1789, Fleming once again took the Wilderness Road through Cumberland Gap, attempting to untangle his land claims in Kentucky. Returning from the West, he immediately left for Sweet Springs in modern West Virginia, seeking relief from pain.

In 1794, he wrote a niece in Scotland: “I live in a pleasant situation one hundred eighty miles from Richmond near a big Lick in Botetourt County [in modern Roanoke city]. I have retired from all publick business for several years. I am now old, my constitution broke, maimed by several wounds, and often attacked with violent pains in my limbs, brought on by colds and many years severe duty in a military line.”

His will, written 1795, left Belmont and his enslaved people to Nancy. He died at home on a date not recorded. He was buried in the family cemetery on the rise above his house alongside his mother-in-law and the children who had died young. Nancy died around 1810 and is buried beside him. A Roanoke chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution is named for her.

The mortal remains of William Fleming are presumably long gone, but the lead ball, as far as anyone knows, is still there.

Belmont burned around 1875. Ole Monterey Golf Course was built around the home site and graveyard.

State historic markers in Roanoke and Staunton commemorate Dr. Fleming, and one of Roanoke’s two high schools is named for him. As a supporter of education, he probably would have liked that.

Much of this story was taken from “William Fleming, Patriot,” by Roanoke Valley historian Clare White, published in 2001 by Gateway Press and the History Museum and Historical Society of Western Virginia.