When the New River at Radford edged just over 31 feet — an amazing 17 feet above flood stage — last Sept. 28 with the overwhelming outpouring of Hurricane Helene swelling northward, there was one high water mark from the past that it didn’t top.

On this mid-August week 85 years ago, Southwest and Southside Virginia and much of western North Carolina were inundated by a mighty tropical downpour over multiple days that was very much echoed — exceeded in some places, not quite equaled in others — by the inland effects of Hurricane Helene a little less than 11 months ago.

Last September’s 31.03-foot flood would have needed almost another 5 feet to reach the 35.96-foot line on the Aug. 14, 1940, historic marker in Radford’s Bisset Park, nearly 22 feet above flood stage.

The same two floods are also ranked first and second, historically, for New River gauges at Allisonia (23.42 feet on Aug. 14, 1940, 22.29 feet on Sept. 28, 2024, 8 foot flood stage) and Galax (25.7 feet on Aug. 14,1940, 21.26 feet on Sept. 28, 2024, 9 foot flood stage).

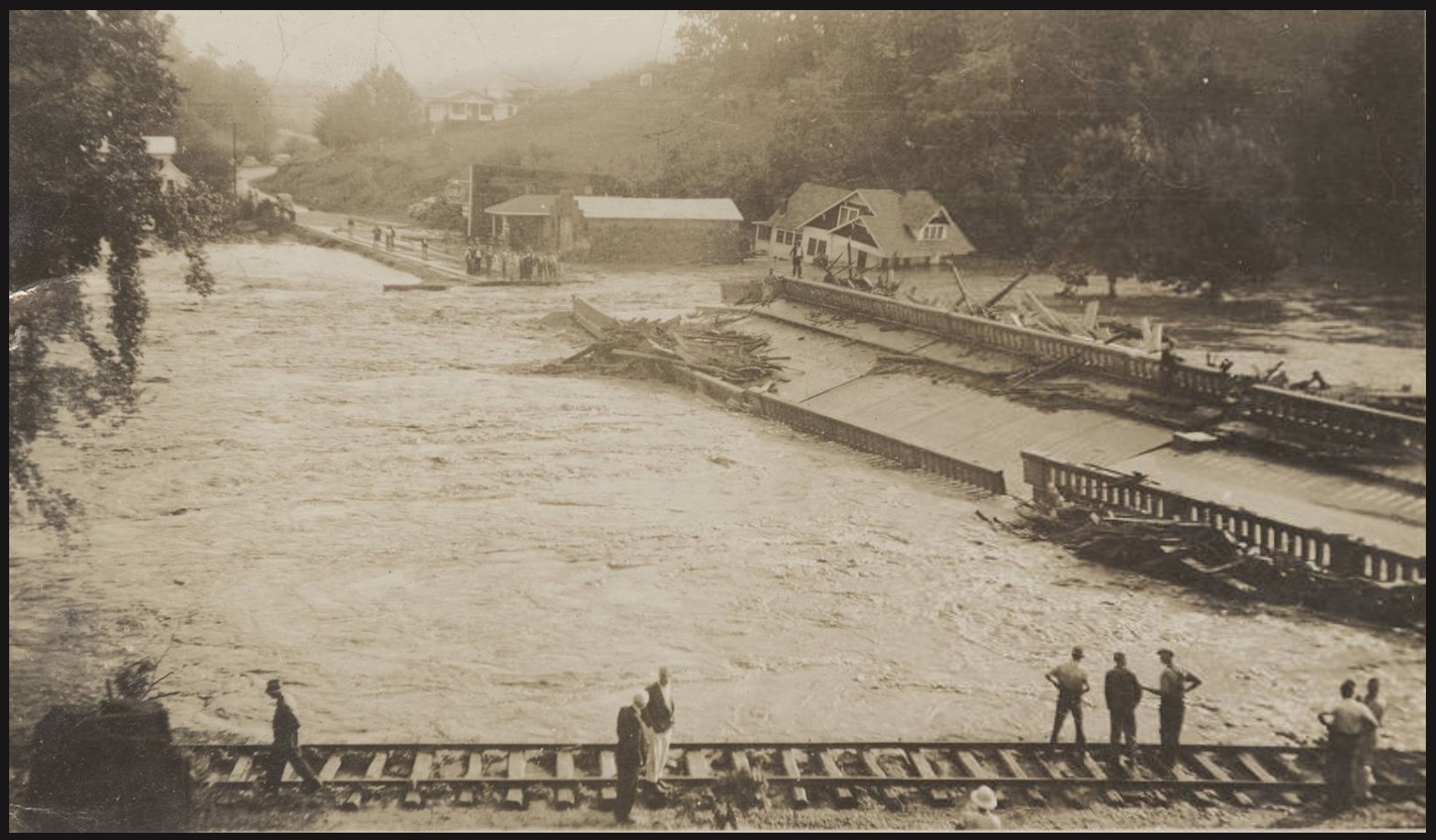

Several hundred people were forced out of their homes by flooding along the New River.

At Galax, in 1940, according to “Hurricanes and the Middle Atlantic States” by Rick Schwartz (this writer was an editor for the book), hundreds of residents also had to leave their homes when Chestnut Creek “expanded to several times normal” and reached the top of some houses.

At Farmville, flooding on the Buffalo and Appomattox rivers cut off outside routes for the town’s 3,000 residents.

Five fatalities in Virginia have been attributed to the 1940 floods, with $750,000 in highway damage, as retold by a report five years ago from WFXR, the Roanoke Fox television affiliate.

In western North Carolina, some accounts refer to the 1940 flood as the “second great flood” in the region, following the infamous 1916 event that has drawn many comparisons to Helene with its rampant flooding and mudslides. Stories recalled from the flood’s wrath were recounted in an article for Our State by historian Philip Gerard.

On the Swannanoa River at Biltmore Village near Asheville, North Carolina, last September’s torrent is far and away the worst on record, going over 27 feet where the flood stage is 10 feet. But grouped very closely at second, third, and fourth place are the infamous July 1916 storm with an almost 21-foot crest at Biltmore Village, a September 2004 flood at 19.22 feet, and Aug. 13, 1940, at 19 feet.

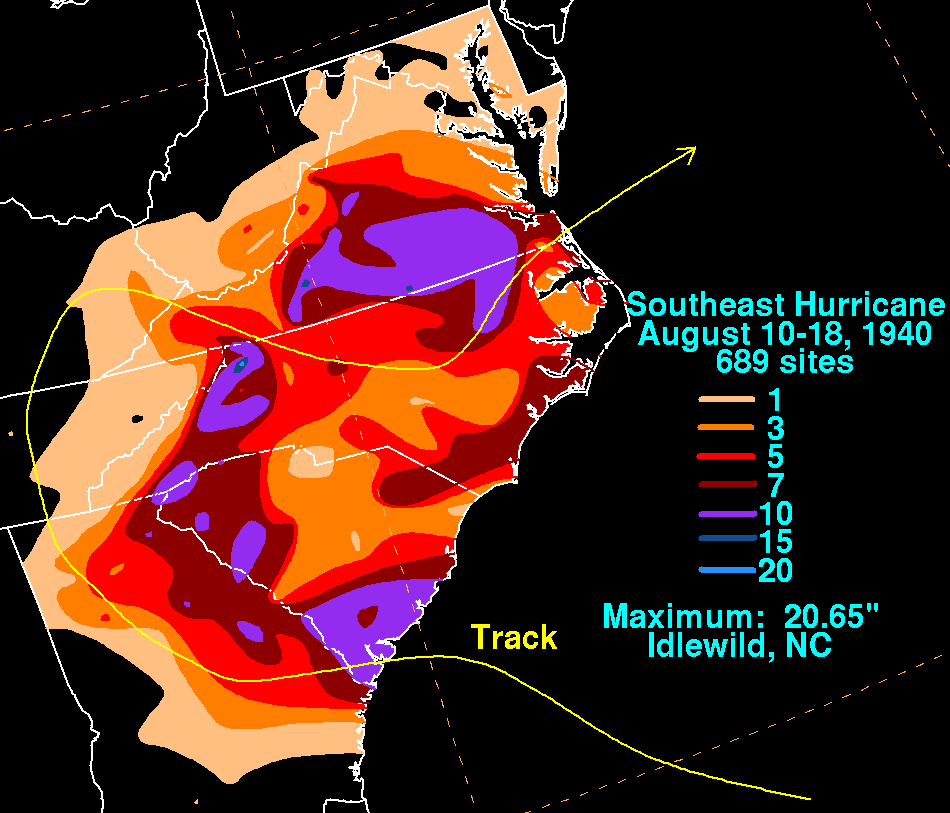

All four of those floods had the same general cause: Inland tracks of tropical systems. In 1916 and 1940, hurricanes tracked inland northwestward after a South Carolina landfall, dumping enormous rains in steep terrain as the systems’ winds weakened but the circulation center dawdled near the mountains before turning more northeast. The 2004 flood was related to the remnants of Hurricane Frances, which came ashore on Florida’s east coast, curving into a steady north-northeastward track over western North Carolina and Virginia. It had been fairly dry leading up to Frances in Southwest and Southside Virginia, so the flooding was generally not extreme in our region.

Helene was a different beast, making landfall on the Gulf Coast in Florida’s Apalachee Bay, then getting pulled north-northwest and absorbed into a powerful upper-level low to the west. That resulted in continuous upslope flow into the steep terrain of western North Carolina and Southwest Virginia, falling on top of two days’ worth of heavy rain with a “predecessor rain event” related to Helene but not directly a part of it, all augmented by unusually strong winds maintained far inland by the interaction with the upper-level low, especially in higher elevations. (“Why was Helene’s impact so bad for us?,” Oct. 2, 2024, in Cardinal News.)

The heavy rains of 1940 were centered a little farther north and east relative to Helene’s swath. There were reports of 12-16 inches of rain in Floyd and Patrick counties. This enhanced the flooding in the New River and caused the Roanoke River to reach some rare heights.

The Roanoke River crested at 18.25 feet, 8¼ feet above flood stage, at Roanoke’s Walnut Avenue bridge on Aug. 14, 1940. That was the highest crest recorded on the river since 33 years before and for another 32 years afterward, when Hurricane Agnes’ inland shield of rain pushed the river to 19.61 feet in June 1972. Then, 13 years after that, came the infamous Flood of 1985 at 23.35 feet, connected to the remnants of Hurricane Juan.

Roanoke’s record monthly rainfall did not happen in November 1985 with that big flood as a major component, but rather in August 1940, when 16.71 inches was measured. That topped the 12.36 inches of November 1985 rainfall by more than four inches. In both cases, almost 10 inches of rain fell within 4 days — Aug. 13-16, 1940, and Nov. 1-4, 1985.

Downstream from Roanoke at Altavista, the Roanoke River topped 40 feet in 1940, 22 feet above flood stage. That’s almost six feet higher than any other flood on record at that location.

One should always be sensitive declaring any particular flooding event to be the worst, as this differs across our region. Camille in 1969 (truly a cataclysm for Nelson County), Agnes in 1972, Juan in 1985, Fran in 1996, the Frances-Ivan-Jeanne triple-play in September 2004, Michael in October 2018, and, of course, Helene last fall are among the memorable flooding episodes from tropical remnants in different portions of our region. There have also been other flooding episodes not related to tropical systems like the recent Dante cloudburst and the February flooding in multiple Southwest Virginia counties.

For locations along the New River and a few other spots around the region, August 1940 still stands as the worst that has been experienced in recorded regional history.

Journalist Kevin Myatt has been writing about weather for 20 years. His weekly column, appearing on Wednesdays, is sponsored by Oakey’s, a family-run, locally-owned funeral home with locations throughout the Roanoke Valley. Sign up for his weekly newsletter: